Invisible Interventions: Notes from the Helsinki Biennial

Its 2025 edition, ‘Shelter’, seeks to disturb our anthropocentric attitudes by swapping spectacle for subtlety

Its 2025 edition, ‘Shelter’, seeks to disturb our anthropocentric attitudes by swapping spectacle for subtlety

08:05

I’ve just woken up in a large, empty hotel room in Helsinki. Last night, after I complained of being slightly ill, someone told me that whisky helps to clear congestion – then promptly ordered me a double. Any restorative effect has now worn off. I’m here for this year’s Helsinki Biennial, curated by Blanca de la Torre and Kati Kivinen. Titled ‘Shelter: Below and Beyond, Becoming and Belonging’, its works are united by a concern with the relationship between humans and other forms of life. In their introductory statement, the curators outline a focus on ‘displacing the anthropocentric gaze’. It’s an intriguing, if characteristically vague, starting point for a biennial.

08:41

Having skipped breakfast, I arrive at the Helsinki Art Museum (HAM), one of the exhibition’s three venues. The presentation at HAM opens with a large, multicoloured sculpture of a flower by Yayoi Kusama (Flowers that Bloom Tomorrow, 2011). It’s a strange opening note for a biennial whose curators claim, in their introduction, to be ‘divesting humans of sole leadership in the presented artworks’. Kusama is one of the world’s most famous artists, and it’s difficult to see how she doesn’t have ‘sole leadership’ over a sculpture that, covered with her trademark polka dots, is so clearly an expression of the artist’s personal – and distinctly human – vision of the natural world.

08:53

There are more promising works in HAM’s main gallery space. I’m particularly struck by Edgar Calel’s RäxRoj K’ux (Green-Blue Spirit, 2025), a group of black embroideries on white canvas that have the appearance of simple line drawings. In one, Calel depicts a cluster of bamboo shoots with a line of ants marching away from its base. This work isn’t proclaiming its urgency; it’s not suggesting that art can fix, or even meaningfully change, the world. Instead, Calel simply looks at nature, presenting the visual record of what he sees.

10:52

After a short coach ride to avoid a sudden onset of rain, our visit continues in Esplanade Park, where the work of five artists has been installed among the trees and fountains. Most interesting is Bug Rugs (2025), a set of four large insect hotels by Kalle Hamm and Dzamil Kamanger that mimic the designs of traditional Kurdish and Finnish rugs. It’s a neat idea, but any positive ecological effect arising from these elaborate insect environments is surely undercut by the fact that, at the end of the biennial, they will be removed from the park. Since its inception in 2021, the Helsinki Biennial has strived to minimize its environmental impact – but, as with most major art events, the result still frequently feels like a temporary invasion of the city.

11:40

A ferry takes us to Vallisaari island, the most inaccessible of the biennial’s venues. The water is steady enough, but I still feel slightly nauseous – and am relieved when we begin to turn towards an island covered in dark trees.

12:28

After visiting several works on Vallisaari’s poorly marked trail, we arrive at Raimo Saarinen’s Invasive Scent (2025), which, according to a board at the side of the path, is ‘an olfactory installation consisting of three different plant scents’. There is no visual component to this work, and although my nose is blocked, other critics confirm that there is no obvious scent. As the accompanying text states: ‘The island’s visitors and non-human cohabitors are invited to judge for themselves whether the aromas of these species blend into the existing landscape of scents.’

Standing around and sniffing the air, our gaggle begins to look like a parody: we have all been cast in the role of the pretentious art critic from some 2010s American sitcom, who goes into a forest not because he thinks the nature is beautiful but because he has been told there is a conceptual artwork there.

13:40

Over the past hour, I have seen leaves and branches injected with bioluminescent fluid (Juan Zamora, To Embody an Island, 2025); I have listened to a work that amplifies the sound of worms in a compost heap (Tamara Henderson, Worm Affair, 2023); and I have pulled on a rope attached to hundreds of seed-filled pods, making them rattle like a manically handled rain stick (Tania Candiani, Sonic Seeds, 2025). Still, few of the works on Vallisaari captivate me as much as Invasive Scent. Every so often, as we walk around the island, someone stops and sniffs the air, trying to decide if a certain patch of woodland smells a little too strongly of wild garlic.

14:00

A few critics, myself included, took a wrong turn on the Vallisaari trail and ended up walking part of it in the wrong direction, visiting the artworks in reverse order. As such, what should have been one of the first works we encountered – Tue Greenfort’s Limulus Polyphemus Lampisaari (2025), a series of concrete-cast horseshoe crabs – is the last work we see. The placard promises a ‘consortium of crabs’, but we cannot, at first, spot any. We climb past a warning sign onto a stone jetty, in case they are there, and then – with none in sight – traipse down an overgrown path to a small, rocky patch where the water grazes the shore. Here, at last, we see them, lying flat among the craggy rocks: a line of five horseshoe crabs, crawling up the beach one after the other, their grey colouring acting as camouflage. They are subtle, realistic casts, and after so much searching for the promised ‘consortium’, this meagre cluster is an oddly underwhelming climax. As one fellow critic says: ‘Ending on the crabs was brutal.’

15:04

The ferry having returned us to Helsinki proper, we walk back to our hotel, crossing Esplanade Park on the way. Standing in front of Geraldine Javier’s wall of fabric-wrapped talismans (Earth, Water, Air, Fire, Void, 2024) are two children rapping into wireless microphones, their voices altered by autotune and projected through speakers into the surrounding park. A crowd has gathered, corralled by several enthusiastic teenagers. We ask one of them if this performance is related to the Helsinki Biennial. ‘What’s that?’ she asks. Further into the park, children are being encouraged to spray-paint a length of black polythene that has been stretched between two trees. Elsewhere, a busker sings Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’, his voice cracking a little as he croons. The park is full of people gathering, performing, gossiping, resting, flirting – many of them oblivious to the works of art on display.

Maybe this is what the Helsinki Biennial is all about: making small alterations to an environment, without the artist’s presence ever being too strongly felt. This kind of subtlety is a through line in many of the works on display: the freshly installed Bug Rugs look weathered, as if they could have been in Esplanade Park for months, if not years; it’s unclear if the Invasive Scent even exists; and the crabs of Limulus Polyphemus Lampisaari lie on a difficult-to-find beach. That its works are easy to ignore might be an odd measure of success. Yet, for a biennial that seeks to disturb our human-centric attitudes, perhaps it makes sense for the art to blend into nature – understatement becoming a politics of its own.

‘Shelter: Below and Beyond, Becoming and Belonging’ is on view across various locations in Helsinki until 21 September

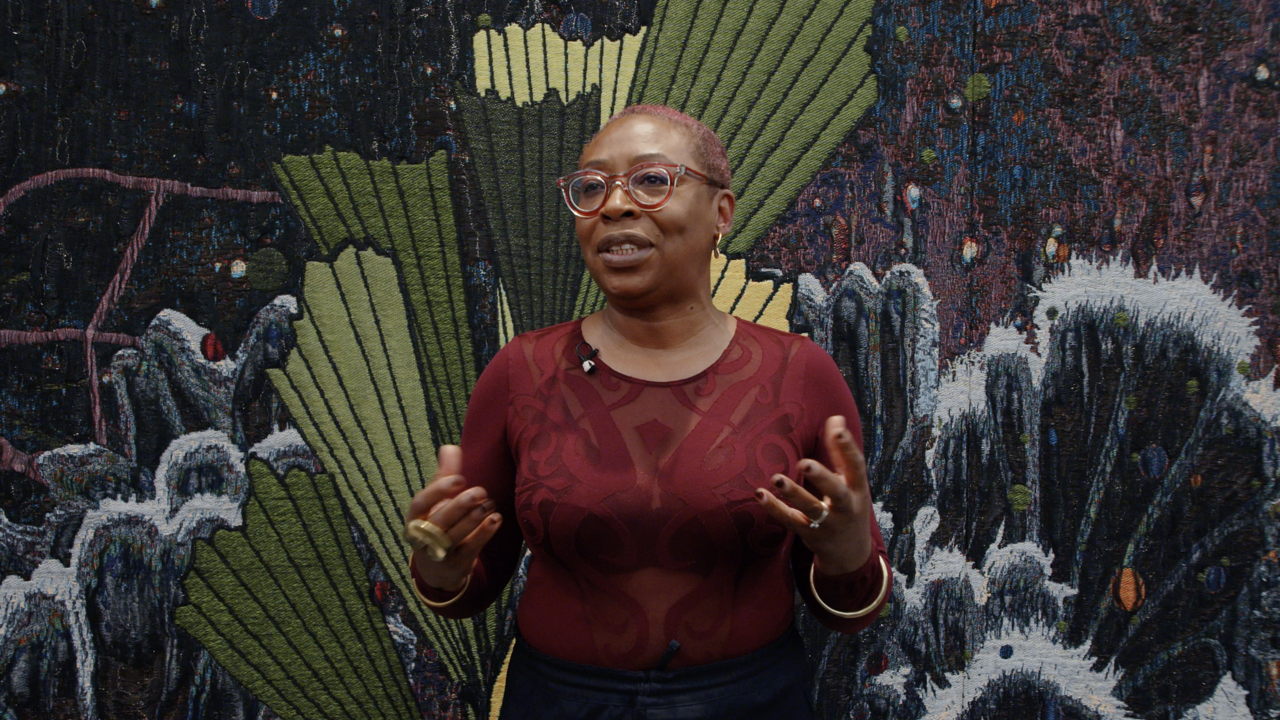

Main image: Juan Zamora, To Embody an Island (detail), 2025, Helsinki Biennial, Vallisaari Island. Photograph: HAM / Helsinki Biennial / Maija Toivanen