The World from rue Madame: Celebrating Etel Adnan

For Adnan, art and politics need not be in conflict

For Adnan, art and politics need not be in conflict

What does the world look like from rue Madame, where the artist Etel Adnan lives in Paris? Is it sun-kissed and static, like a mountain, or does it surge, jubilant, with the thrum of music, laughter, speech? How far are we from flickers of bombs, from Algiers and Beirut, or from the roaring of northern Californian waves?

Few of us – fewer still, under lockdown – will know this view, any more so than the geography of Adnan’s life. Memories are figments and no one owns the past. Just as the past passes through us, changing us, Adnan is, herself, now a kind of touchstone – for her many friends, students, readers and viewers. For this celebration of Adnan’s life and work, we have solicited words from some of these fellow travellers.

But who is Etel Adnan? It would sound too passive to say that this poet, activist, filmmaker, painter, teacher and writer has ‘borne witness’ to a near-century of tumult: in 1941, aged just 16, she worked at the French Press Bureau in Beirut as the German army occupied Paris. Yet, she has continued to maintain that fiction and document, art and politics, need not be in conflict. That’s the word on rue Madame.

Whatever form they take, the voices and images in Adnan’s cosmos are manifold. All art is polyglottic, knotted with inflections, turns, anacoluthons, cul-de-sacs. And, just as there is no single language for any artist, with Adnan – whose work cuts through media – it makes sense to start with the politics of the tongue: language, that split and searing liturgy.

Born in Beirut in 1925, to a Greek Orthodox mother and a Turkish Muslim father, Adnan spoke Greek and Turkish at home – Arabic was forbidden – and, eventually, French and English. Just after the Lebanese Civil War, she published (in French) her novel Sitt Marie Rose (1978), which strings together monologues, news and interviews to tell the story of Marie Rose Boulos, a Lebanese Christian who was kidnapped, tortured and murdered by Christian militiamen in Lebanon after expressing her sympathy for Palestinians.

No language is neutral and, during the Algerian Revolution (1954–62), in protest against French colonial rule, Adnan ceased writing in French. ‘I realized that I couldn’t write freely in a language that faced me with a deep conflict,’ she observed in her 1996 essay ‘To Write in a Foreign Language’. Adnan travelled: in Algeria, she discovered the Moroccan radical poetry magazine Souffles; in Beirut, she cherished the poems of Adonis and Yusuf el-Khal; in Paris, she studied with philosopher of space Gaston Bachelard; and, in Mexico, she wandered.

But it is northern California, where Adnan spent many years, that remains the bedrock of her paintings. Adnan took to the canvas later in life, in the 1960s, after arriving at the Dominican College in San Rafael to teach philosophy of art. It was there that, urged by a fellow teacher, she discovered: ‘I didn’t need to use words, but colours and lines. I didn’t need to belong to an open form of expression […] I didn’t need to write in French anymore, I was going to paint in Arabic.’ Her views of Mount Tamalpais in Marin County – each unique, each alike, with patchworks of conflicting colour – are among the most iconic landscapes of our age.

When I invited these authors to contribute, they responded with speed and generosity: the writer Negar Azimi noted that ‘we could all use some Etel ray of light right now’, while director of Dar al-Ma’mûn (a library and residency for artists and translators) Omar Berrada sent a recent photograph of himself with Adnan in Paris. Soon after, we heard the news that Sarah Riggs had won Canada’s 2020 Griffin Poetry Prize, one of the world’s leading poetry awards, for her translation of Adnan’s Time (2019). Here, renowned poet Joan Retallack takes a close reading of Adnan’s enjambments of thought, word and line.

But it is Adnan’s work itself, excerpted here, with which we can begin and end: it contains multitudes about age, travel, mobility, loss. It is a fable of the constriction many of us find ourselves living with today and of how art can serve as eulogy and release.

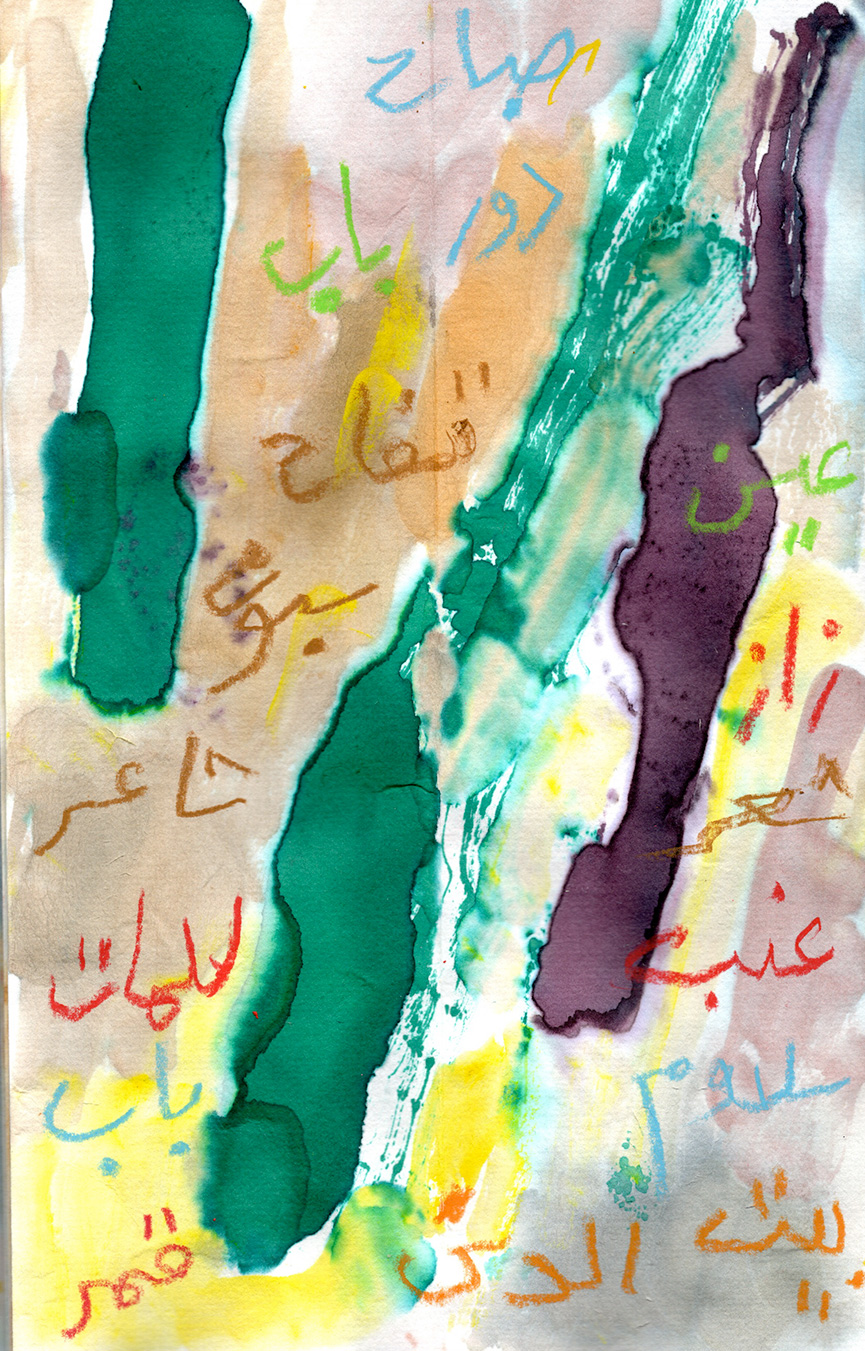

Main Image: Etel Adnan, Jardin Enchanté, 2017–2018, wool tapestry, 1.5 × 2.1 m. Courtesy: Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut/Hamburg