How Martin Margiela Transformed Fashion’s Cast-Offs

Can Reiner Holzemer’s documentary finally lift the lid on the famously private designer?

Can Reiner Holzemer’s documentary finally lift the lid on the famously private designer?

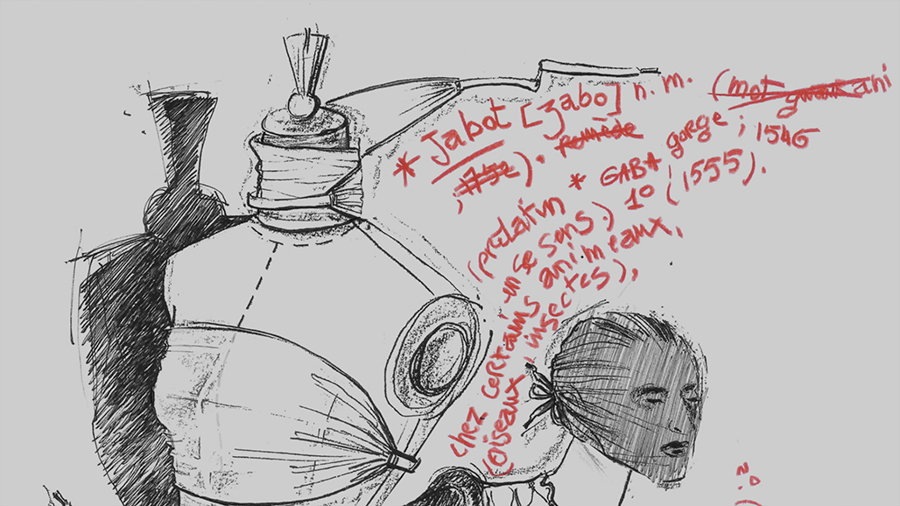

Martin Margiela in His Own Words (2019) – Reiner Holzemer’s latest documentary – opens with a pair of hands, deft and decisive, working with a discarded champagne cork. These hands, belonging to the Belgian fashion designer, are all we see of him, beyond an indistinct face glimpsed within a busy studio in the broad setting of old photographs. The hands apply modelling clay to the cork head, place a metal cap firmly back in place over it, twist the metal cage tightly closed and string a black cotton ribbon around its waist. We follow the hands as they delicately lay this totem around the neck of a dressmaker’s mannequin as if it were a jewelled pendant.

The party is over. In the unforgiving light of a new dawn, the trappings of yesterday’s revelry look tawdry, embarrassing. What a metaphor for fashion. Who might re-invest these champagne corks and fallen silks, trampled confetti and dropped hems with the excitement that once charged them? For 20 years – between 1988 and 2008 – Margiela picked up what fashion cast off and transformed it. Not only champagne-cork necklaces, but taped-on shoes and tops, garments rehabilitated with a layer of house paint, and jackets stitched from gloves and socks.

Margiela designed fashion that paraded its own production and dissemination. One collection appeared to offer coarse linen covers sliced off tailors’ Stockman mannequins with half-finished drapery tests still pinned to them. A trademark vest top was stitched to the flat-fold format of a plastic carrier bag. While Margiela’s contemporaries covertly plundered vintage boutiques for inspiration, he bought cheap stock from flea markets, took garments apart and reconstructed them with a tag crediting the source.

Conceptual, appropriative, critical: in the reverent discussion and analysis of Margiela’s work, the language of art has become a commonplace. Not only because it seems well-suited to the sense of purpose informing Margiela’s confections, but also because the designer himself refused to supply a readymade discursive framework. For the two decades in which he headed a fashion brand so discreet that its garments carried blank labels, Margiela allowed himself to become an enigma: he did not appear on the runway to receive applause, he made no public appearances, he gave no interviews.

For a certain fashion-world elite around the turn of the 20th century, Margiela inspired tribal adherence. Devotees were assumed intellectual; hovering, pristine, above the sullying tide of trends; untouched by the coarse desire for clothing that bestows sex appeal, prettiness, form-flattery.

Margiela stepped away from the house that carried his name in 2008. Already, the retrospection, celebration and analysis had begun: a studious exhibition was held that year at MoMu Fashion Museum in Antwerp, where Margiela had attended the Royal Academy of Fine Arts alongside the designers later known as the ‘Antwerp Six’. The exhibition toured internationally and, in 2018, a further retrospective was staged at the Palais Galliera in Paris. There have been books. Still, the designer held his peace.

In an age that places great weight on testament, the promise of Martin Margiela in His Own Words feels significant. What happens when the great man speaks? Are there silken shockwaves? Does the temple of fashion crumble? Plot spoiler: no. This designer of garments that direct the wearer to introspection rather than broadcast is, unsurprisingly, thoughtful and private. He passes no comment on the British designer John Galliano, who – having been arrested and prosecuted in 2011 for racist and antisemitic abuse, which led to his being sacked by fashion house Dior – was appointed, post-‘rehabilitation’, as creative director of Maison Margiela in 2014. He makes no mention of the casual appropriation of his designs (notably by the hyped brand Vetements). Instead, he talks as though we were in the studio beside him as he gets on with the more important job of making.

Margiela’s mother kept an archive of his early years – including dolls whose hair he dyed with vinegar, and for whom he’d tailor modish jackets. Leafing through a childhood sketchbook, he offers us glimpses of these precocious precursors to his adult designs. He mentions the faces his parents’ friends would pull when he told them he’d one day be a fashion designer in Paris. Margiela grew up in the mining town of Genk, where his father ran a hair salon and his mother sold wigs. This bestowed a fascination with hair that would translate into garments constructed from artificial tresses and wigs that masked the face. For Margiela, concealment and anonymity was a design aesthetic as well as a personal choice.

There are other talking heads in this documentary, notably designer Jean Paul Gaultier – for whom Margiela worked before launching his own label – and fashion critic Cathy Horyn. Most adopt the standard fashion-industry approach of telling us earnestly how wonderful and significant things are without quite explaining why. We are shown footage of early catwalk shows filmed during the era of VHS; the quality is terrible and we must squint for details.

Margiela tells that he never explained his work because he wanted it to speak for itself. His silence was not intended as a great statement, so it seems in keeping that his breaking of that silence is hardly revelatory. Rather than the voice, it is the hands that moor this film: gently forming, unpacking, folding, dressing, taping garments. We waited decades to hear him but, perhaps, after all, he had nothing to tell us that was not already there to be discovered.

‘Martin Margiela in His Own Words’ is available to stream via Curzon Home Cinema and iTunes

Main image: Reiner Holzemer, Martin Margiela: in His Own Words, 2019, film still. Courtesy: Dogwoof