The Secret History of Weeds

What a garden’s lowliest plants can teach us about resistance to capitalism and patriarchy

What a garden’s lowliest plants can teach us about resistance to capitalism and patriarchy

‘What is a weed?’ Ralph Waldo Emerson asked the crowd that had gathered to hear him speak at Boston’s Old South Church on 30 March 1878. His answer: a plant not yet useful. There were some 200,000 weeds, he noted in his lecture, ‘Fortune of the Republic’, adding: ‘Time will yet bring an inventor to every plant. There is not a property in Nature, but a mind is born to seek and find it […] The infinite applicability of these things in the hands of thinking man, every new application being equivalent to a new material.’ He was referring to capitalism and control and dominating the land. His story is that of a man, of a white man, of a ‘thinking man’.

My weeds are not Emerson’s weeds. The ones I see hold stories of globalization and mass migrations. Most of the weeds in the US are here because someone once thought they were useful. The language around them today is problematic: ‘native’, ‘invasive’, ‘alien’ – as if a microcosm of our politics. I look at my scraggly lawn and it’s all weeds. There’s chamomile and oxeye daisy, which has been called a ‘dangerous ornamental’ by the National Park Service and tastes like rocket in salad; yarrow that Achilles carried to staunch his troops’ wounds; prunella, known as ‘self-heal’ or ‘heal-all’ for its medicinal properties; red clover that can be used as animal feed or to moderate women’s hormones. There are docks and plantain.

These plants and their histories are not simple. They were often brought by white colonizers. Plantain is also called ‘white man’s foot’ because it travelled everywhere white people went. Its young leaves make salad greens rich in nutrients and as a salve – even chewed up in saliva – work as a great healer of cuts.

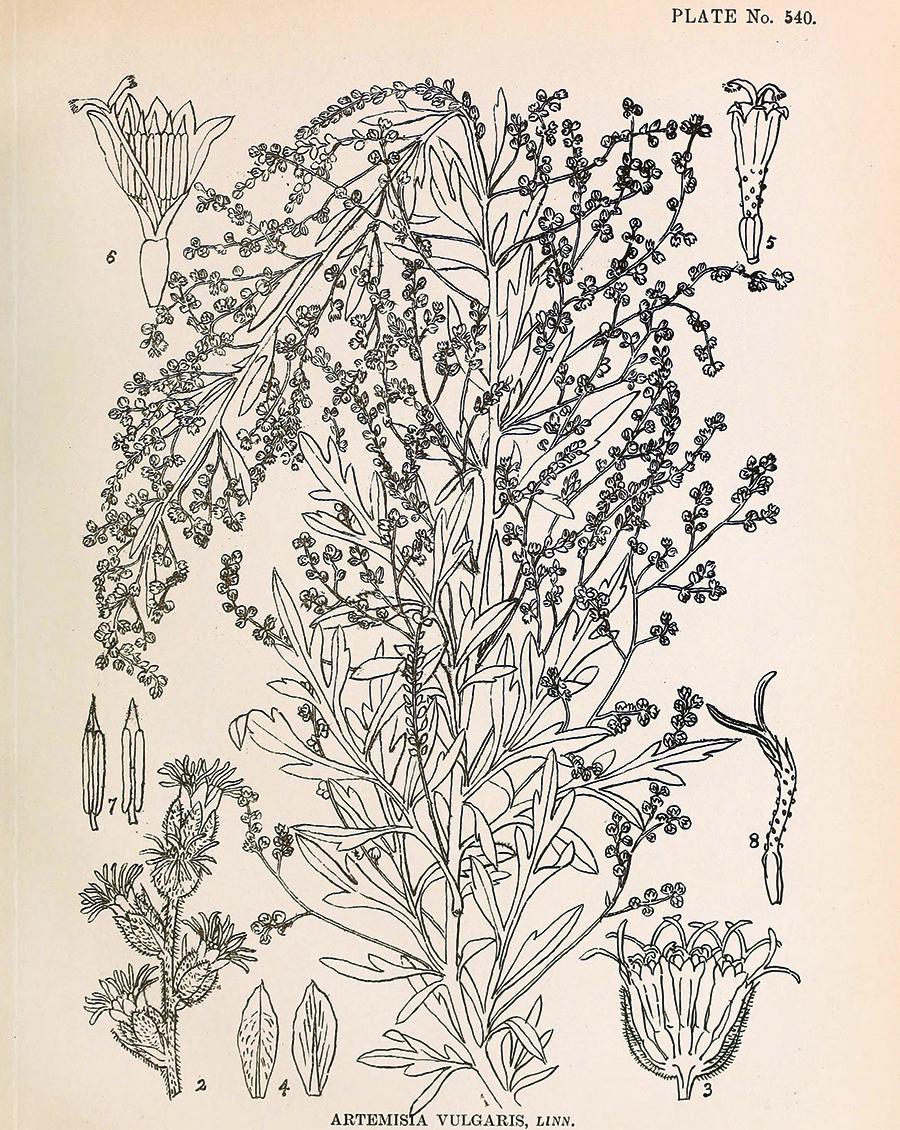

Other weeds hold secrets of resistance. Queen Anne’s lace, with its bobbing white heads, is a wild carrot. The root is edible, but its seeds are another story – or, rather, they are my story. They are a progesterone inhibitor and can work like the morning-after pill or, taken daily, as the contraceptive pill. Mugwort’s long fronds wave at the cars that race past it on roadsides. Its leaves, with their silvery undersides, smell of pine and sage. They are a potent source of thujone, a natural compound with psychotropic qualities. Rumoured to be the reason witches fly, the plant sparks vivid, racing dreams. It also modulates women’s hormones and can induce abortion. Its roots are a rhizome, spreading exponentially. Seeing it in Brooklyn along the polluted Gowanus Canal, I think of the women who must have brought it here with them and imagine their needs, fears and dreams.

Mugwort, with its muddy-sounding name (‘wort’ means root), is the beginning of the ‘Nine Herbs Charm’. Published in the Lacnunga, a book of herbal remedies from the late 10th or early 11th century, the spell invokes the plant as if it’s alive and present:

Mind you mugwort

what you disclosed

what you rendered

at Regenmelde

The first you are called

oldest of plants

you mighty against three

and against 30

you mighty against poison

and against infection

You mighty against the evil

that fares through the land

After I read the charm, mugwort – the ‘first’ and ‘oldest’ – became a sign of rebellion to me. Donald Trump was president then and challenging women’s reproductive rights; I wanted this plant everywhere, along roads and in cyclone fencing, in parking lots and poor soils. As I ran through Prospect Park in the morning, I’d salute it. I see its fronds in summer and think of the lost histories of women. The first time I took it, in 2018, I followed directions a gardener at The Met Cloisters museum in Manhattan had given the artist Marlene McCarty. I had dreams of

packing a child’s red backpack emblazoned with cartoon characters and fleeing in a forced migration – an apt vision it seems, looking back.

When the charm was committed to writing, it was one of the last holdouts against Christianity. Four centuries later, vast numbers of women would be persecuted as witches for their herbal knowledge and, as farming developed into monocultures – with crops set out in rows and lines like single-point perspective – land itself became men’s wealth and inheritance. Then came colonization, capitalism, slavery and the stripping of women’s power over their lives and bodies. Medicine became man’s domain, too. In the US, white settlers – with the government’s sanction – stole land from and killed Native Americans because they wanted ever more territory to plant their waves of grain and cotton.

Emerson delivered his speech near the start of the Long Depression (1873–96), and he was addressing the economics of cotton and the Civil War in an argument I don’t fully understand. That depression sparked a counter-narrative to farming and capitalism. The year Emerson spoke, Black and white sharecroppers growing cotton in the South were aligning – not the story we often hear of the post-Reconstruction era – and their joint power terrified white supremacists. These farmers were being screwed over by capitalism, by merchants and banks and cotton brokers. Forming the Farmers’ Alliance in 1877, they raised class consciousness across racial lines. The group fought for unions, co-ops and socialist reforms of banking and railways. Cotton itself has been a tool of resistance, too: enslaved women carried knowledge of the plant from Africa where it also grows. Cotton, or gossypium as the genus is called, has abortifacient properties and, I’ve read, can suppress sperm.

Reading the ‘Nine Herbs Charm’, I think about the ‘Unicorn Tapestries’ (1495–1505). One of my grad students, Kate Brock, is writing about them and points out the millefleurs technique, with flowers dotted everywhere, becoming the ground, the air, the aether. There is nothing between the plants and us. These tapestries were made around 500 years after the ‘Nine Herbs Charm’ was recorded, but the technique they employ is from the gothic era. Those plants and flowers suffuse everything; human figures stand amidst them as if part of the foliage. In the later tapestries, Kate notes, the flowers are reduced and tamed. They become a line beneath the unicorn hunters’ feet. The plants and soil are now under our domain.

What is a weed? Mine are an economy of the waste places, prying through cracks in the pavements of toxic dump sites, parking lots and highway verges, where they can help remediate the soils. The US spends $20.5 billion annually on pesticides for monocultures to grow crops, spreading 23 million tonnes of fertilizer on high-yield varieties of corn, soybeans and wheat. Most fertilizer is nitrogen-based and requires methane to be produced. Methane is the main driver of climate change.

My weeds stand against that. They grow outside the rows, outside the lines, asserting other narratives. These plants no longer deemed useful, which capitalist farming sets out to destroy, can help reclaim those lost landscapes. Docks are rich in iron; yarrow is anti-inflammatory and antiseptic. Plantain can phytoremediate some insecticides. Self-heal’s litany of beneficial properties include anti-ageing, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory. In the summer, I pick and eat its purple flowers as I walk through the grass that is not grass, but a weed, and that tells stories of my own resistance.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 218 with the headline ‘In the Weeds'.

Main image: The Unicorn Crosses a Stream, from ‘Unicorn Tapestries’, 1495–1505. Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York