What to See in East London During Gallery Weekend

Amid a glut of painting and portraiture, a few artists are experimenting with video, photography and animation

Amid a glut of painting and portraiture, a few artists are experimenting with video, photography and animation

Sanya Kantarovsky

Modern Art

8 May – 12 June

Painting is everywhere these days. Isn’t that depressing? I was especially worried about Sanya Kantarovsky at Modern Art, a painter at risk of repeating himself. I was wrong. In these fantastic new canvases, all of them made during the first phase of the pandemic, Kantarovsky paints fable-like subjects that shudder with violence, loneliness, fear and fleeting beauty. A skeleton births a child, aided by a figure evocative of a German Expressionist horror film (Birth, all works 2020); a faceless person cradles a decapitated head (Salome II); a zombie-grey young woman admires a trippy landscape of lush flora (The House of the Spider). The paintings reminded me of a line from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s notebook of 1840. Hawthorne, like Kantarovsky, plunges into history and myth for a dreamy symbolism that speaks to the modern mood: ‘We are but shadows; we are not endowed with real life, and all that seems most real about us is but the thinnest substance of a dream.’ Painting itself has become a rather intellectually thin substance, especially as galleries beef up their canvas offerings in the face of the pandemic’s hair-raising economic crisis. It’s good to know someone out there still takes this medium seriously enough to do something weird with it.

Peter Hujar

Maureen Paley

15 May – 13 June

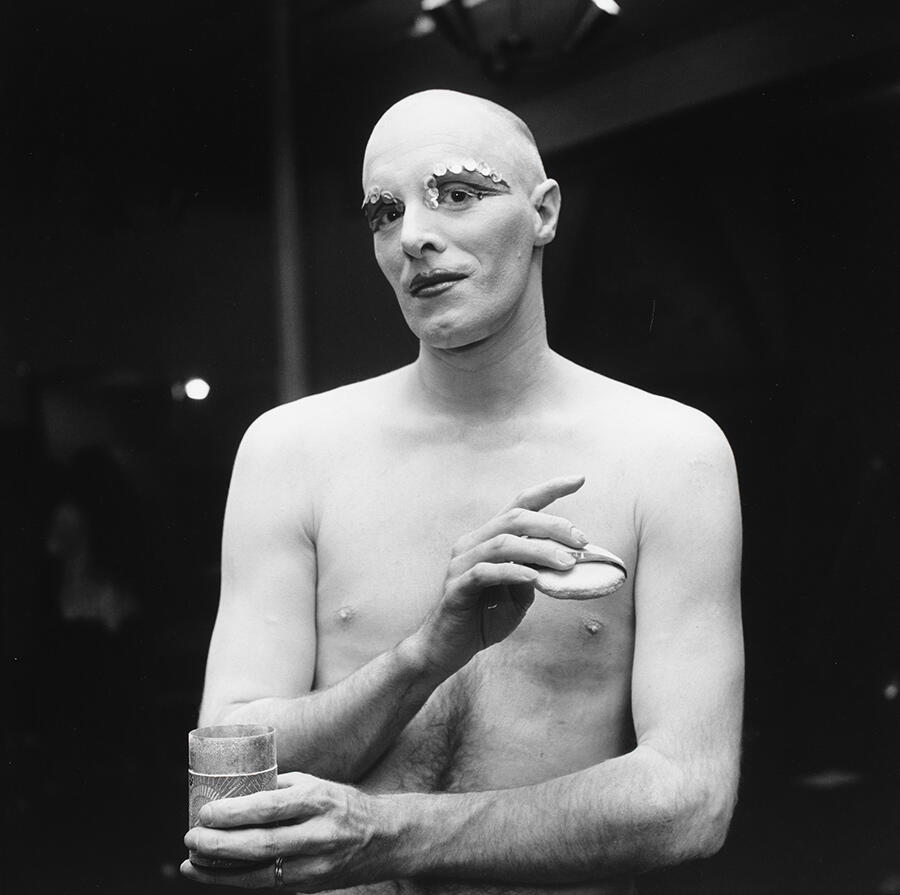

As nightlife resumes in London and New York, Maureen Paley has organized ‘Backstage’ – a collection of Peter Hujar’s behind-the-scenes photographs of performers and friends who worked New York’s clubs in the 1970s and ’80s. Mario Montez, Larry Ree and Georg Osterman vamp and pose (sometimes nervously, to my eye) in various states of dress. Despite their noisy, green-room setting, these are quiet moments for Hujar’s subjects, presented with his characteristic intimacy. David Brintzenhofe applies paint in a 1982 photograph, his face seen in profile, surrounded by dark. In skin-tight trousers, Divine lounges on a divan, head propped up by his hand as he looks off to the side. In a separate room, mostly of photographs of other artists, Paul Thek – once Hujar’s lover – stands on the beach, hands raised as he appears to demonstrate something brilliant. After all, these were exceptional queers, many of whom would perish in an unchecked pandemic a decade or so after they were photographed. As we ‘return to normal’, this show felt like a necessary reminder of what a public health failure can cost us, as well as a quiet exhortation to hold presidents and prime ministers to account.

Matt Bollinger

mother’s tankstation

15 April – 12 June

While I liked many of the works presented in this small show (the American artist’s first in London), I was mesmerized by the 18-minute video tucked between canvases (Between the Days, 2017). Here the artist’s subject matter is animated, with stylistically chubby figures shuffling around post-industrial landscapes, between buildings and places often referred to in the US press as ‘forgotten’. These images draw from and connect the paintings, which show familiar, chain-smoking ghosts from the US exurbs: women and men hooked to oxygen tanks (Candy at Home, 2019) or perusing the local Wal-Mart while security cameras eye their every move (Entertainment Centre, 2020). In one scene in the animation, the coloured glass of a front door is painted and repainted, casting strange shadows on the darkened wall of a house – an eerie minute or so that evoked both the haunted houses of Twin Peaks (1990–91) and the tense suburban nights of Mare of Easttown (2021): two shows about evil and loneliness lying beneath the American heartland. A reminder that the era of Donald Trump might only be between acts.

Invisible Narratives²

Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix

22 May – 19 June

This exhibition continues an earlier collaboration between Rebecca Chesney, Lubaina Himid and Magda Stawarska-Beaven, first presented at Newlyn Art Gallery in 2019. As Himid writes in an accompanying text, these artists explore ‘the invisible layers underneath, the lost spaces on the edge’ of human environments – often so subtly that I was not quite sure I always followed. But the lack of a clear through-line between installations seemed to be the point for an exhibition that seeks to show how knowledge and history are submerged in the everyday fabric of our lives. Take Chesney’s elegant maps of the rivers and waterways in British cities, which the artist has hand-embroidered to reveal old bodies of water – small and large – that have shaped British commerce. You might not recognize her much-expanded Thames in Waterlines (London) (2020); for a thousand years, humans have dammed and shrunk the river to its modern proportions. That old river still muscles through sometimes, like when the subterranean River Effra (an old tributary of the Thames) filches bodies from their graves.

Tosh Basco

Carlos/Ishikawa

29 May – 3 July

At Carlos/Ishikawa, Tosh Basco – also known as the performer Boychild – presents a photographic series depicting stacked images of dying flowers and solemn interiors, including a self-portrait and a lover wrapped in a blanket. Shot using an AE-1 Canon given to her by her father, Basco’s pictures speak to the isolation and intimacy of the past year or so, harkening to the wilted hours of the pandemic, when all was news and booze and increased screen time. These are not slick pictures, nor do they intend to be. Their occasional lack of focus is what lends them an arresting diaristic force. For the press release, the artist writes that these photographs are ‘mementos’ that protest against forgetting. I wonder what Bosco hoped to remember by taking them. It is almost too hard to tell, and the protest they lodge against memory’s frailty slightly interrupts the insight into isolation they might have also provided.

Main image: Rebecca Chesney, Still in Silence, 2013, installation detail, taxidermy blackbird (Turdus merula). Courtesy: the artist and Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix; photograph: Gavin Renshaw