Preview of the 2022 Venice Biennale Part One: National Pavilions

The frieze editors select the projects they are most looking forward to at the National Pavilions

The frieze editors select the projects they are most looking forward to at the National Pavilions

This April, the Venice Art Biennale returns after a three-year pandemic-related hiatus (preview days 20–23; first public opening day 23 April; runs until 27 November). In the third of our five-part preview, frieze editorial staff name which exhibitions they're most looking forward to seeing in the national pavilions of the Giardini and the Corderie dell’Arsenale. To read the second half of our pavilions preview, click here.

Loukia Alavanou

Greek Pavilion, Giardini

Loukia Alavanou’s new VR film Oedipus in Search of Colonus (2022) – debuting in this year’s Greek Pavilion – will be a modern retelling of Sophocles’s Ancient Greek tragedy, which sees Oedipus banished from Thebes and seeking out Colonus as a place to die. Alavanou reimagines the play as an allegory for the experience of the Roma people, who live nomadically but, when in Greece, often are forced by the authorities to search for resting places for loved ones’ bodies far from their traditional territory. Amateur Roma actors portray the roles, lending real-life experience and urgency to the film.

– Marko Gluhaich, Associate Editor

Stan Douglas

Canadian Pavilion, Giardini

In a video about the production of his ‘Penn Station’s Half Century’ (2020) – a series of photo murals depicting nine scenes from a re-created, digital version of New York’s beaux-arts locomotive hub that was demolished in 1963 – Stan Douglas describes the tendency of his work to look at transitional historical moments, particularly instances of rupture during the course of a society’s development. 7 August 1934 (2020), for instance, depicts the Black labour organizer Angelo Herndon greeting thousands of supporters following his release from prison, while 10 November 1941 (2020) restages the farewells of several soldiers as they depart for war. Douglas’s commission for the Canadian Pavilion, ‘2011 ≠ 1848’, which will unfold across a quartet of large-format photographs in the pavilion and the two-channel video ISDN (2022) at Magazzini del Sale No. 5., looks at the working class uprisings that swept Europe in the mid-19th century – including the seizure of the Arsenale by Venetian Revolutionaries from Austrian imperial soldiers and the founding of the short-lived Republic of San Marco (1848–49) – against a trans-continental web of events that began early in the last decade, including the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, the Tottenham riots and the riots following the Stanley Cup final in the photographer’s hometown of Vancouver.

– Patrick Kurth, Editorial Trainee

Latifa Echakhch

Swiss Pavilion, Giardini

In 2011, for the 54th Venice Biennale, Latifa Echakhch lined the gravel walkway leading to its main entrance with 30-odd fibreglass flagstaffs bereft of any flags. At once comical in their material nudity and threatening in their semiotic resemblance to enormous arrows or lances, the crisscrossed poles of Fantasia (2011) formed an introduction to the biennial for visitors en route to the country-based pavilion system. One decade and one pandemic later, Echakhch, who was born in Morocco and grew up in France, will deliver her encore, The Concert, at the Swiss Pavilion, just steps removed from the plain-speaking politics of Fantasia. According to the artist, her sound-focused installation, which stems from her working partnership with the improvisatory percussionist Alexandre Babel and the curator Francesco Stocchi, makes an account of the cyclical, wave-form nature of the fair and is intended to evoke visitors’ memories.

– Patrick Kurth, Editorial Trainee

Maria Eichhorn

German Pavilion, Giardini

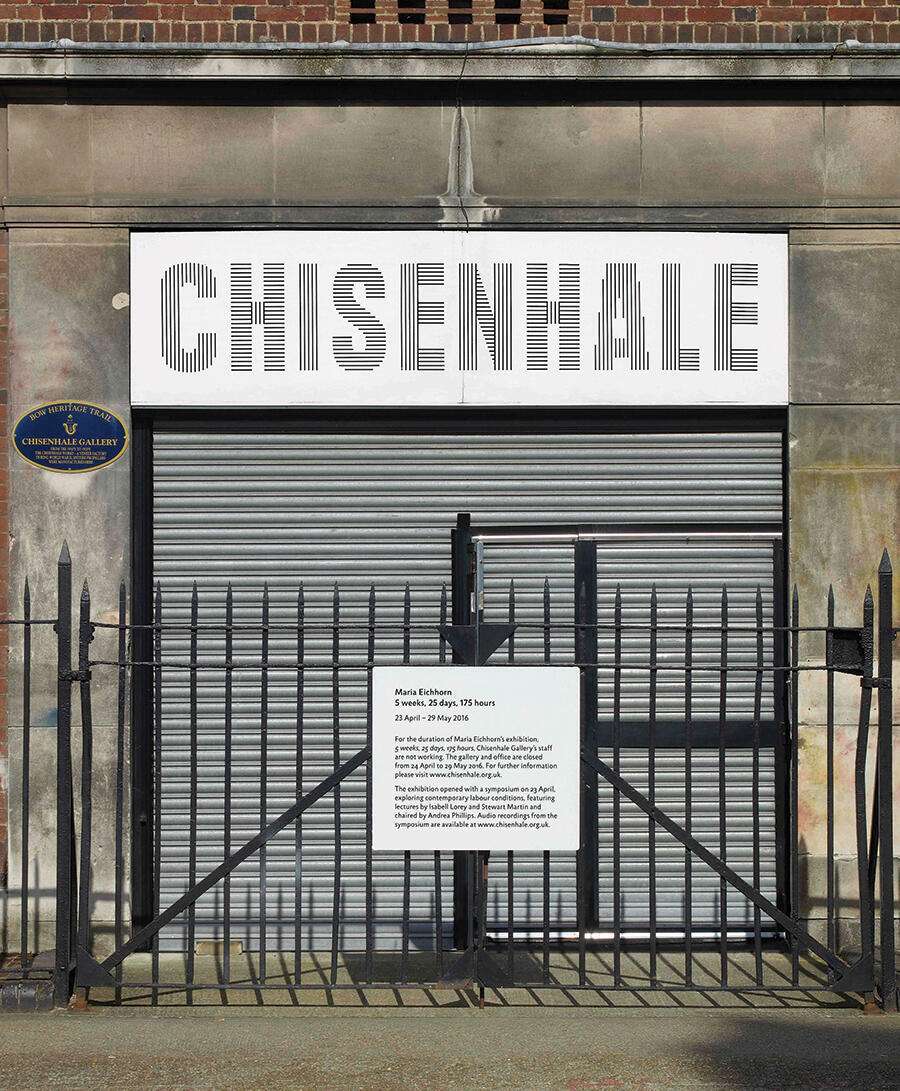

After winning two Golden Lions for the best national pavilion in the past decade – Christoph Schlingensief in 2011 and Anne Imhof in 2017 – the German contribution to the Venice Biennale is always hotly anticipated, but the invitation of Maria Eichhorn (profiled in the April issue of this magazine) seems to have created an even bigger buzz than usual. While Eichhorn’s project is unlikely to be quite as spectacular as Imhof’s five-hour-long, Doberman-guarded Faust (2017) or Schlingensief’s posthumous church (Eine Kirche der Angst vor dem Fremden in mir [A Church of Fear vs. the Alien Within, 2008]), it could end up being just as memorable. Not adverse to controversy, when Eichhorn showed at London’s Chisenhale Gallery in 2016, she shut the whole place down, effectively giving all the staff a free holiday (5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, 2016). Less than a year later, Eichhorn’s contribution to documenta 14 – which saw her establish the Rose Valland Institute (2017–ongoing) to address the theft of Jewish property by the Nazis – was one of the quinquennial exhibition’s most talked about projects.

– Chloe Stead, Assistant Editor

Jakup Ferri

Kosovo Pavilion, Arsenale

As its title suggests, ‘The Monumentality of the Everyday’ – Jakup Ferri’s latest series of canvas paintings and cotton embroideries – bunches quotidian goings-on into riotous and colourful crowds whose sum auras seem slightly askew. The three humans in Glass of Sun (2022), for instance, cradle vases as rain catchers while a fourth hoists an outsized glass to gather tangerine light. The gymnasts that swing from neon trapeze bars and lamp cords in Untitled (2019) are mostly humans in jeans and leotards, though some are apes; the same goes for the nine black and white musicians in a ragtag big band, who are likely playing nine different songs (Untitled, 2022). His are images whose mundanities accumulate up to the brim of realism, forming a meniscus ever ready to spill over.

– Patrick Kurth, Editorial Trainee

Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara and Anders Sunna

Sámi Pavilion (formerly The Nordic Pavilion), Giardini

Of all the many striking buildings in the Giardini, the Sverre Fehn-designed Nordic Pavilion is my favourite. As I wrote back in 2019, the 400-square-metre exhibition space, which features wall-length sliding glass doors and three plane trees growing in its centre, ‘is open to the elements in the truest sense: a celebration of the uncultivated, untamed nature of the architect’s homeland’. This year, the pavilion will be entirely dedicated to Sámi artists, all of whom have a deep connection to the natural world. Máret Ánne Sara and Anders Sunna, for instance, both make politically charged work centred around their families’ practice of reindeer-herding, while theatre director and nature guardian Pauliina Feodoroff has long used her platform to fight for Sámi water and land rights.

– Chloe Stead, Assistant Editor

Marco Fusinato

Australian Pavilion, Giardini

Utilizing elements of sound, media design, interactive installation and social action, Marco Fusinato’s work seems to spring from a tradition that is equal parts Joseph Beuys, John Cage, Guy Debord and Hans Haacke. For the central exhibition of the 56th Venice Biennale, his piece From the Horde to the Bee (2015) solicited funds for a Milanese anarchist collective: a gesture the artist referred to on his website as ‘Part Robin Hoodism, part money laundering’. For ‘Desastres’ at this year’s Australian Pavilion, Fusinato will play guitar live in the space as part of a soundscape that accompanies a chaotic stream of internet-sourced imagery. ‘There’s an assumption that an artist makes work to be liked, and I find that absurd,’ Fusinato told The Art Newspaper earlier this year. Amen to that!

– Matthew McLean, Creative Lead, Frieze Week

Mónica Heller

Argentinian Pavilion, Arsenale

Mónica Heller’s 3D animations come from the hall of Pixar rejects. Unfinished faces reveal exposed teeth and gums, black-eyed humanoids sit on subway cars beside giant, mouse-like furries. Her 2017 exhibition at Piedras Galería in Buenos Aires, ‘Un Paisaje Que No Es Un Paisaje’ (A Landscape without a Landscape), featured several paintings of anthropomorphized wolves and humans chained up on all-fours. In his 2017 essay ‘Something’s Wrong on the Internet’, James Bridle investigates the algorithm-driven playlists for a disturbing subset of children’s YouTube: lo-fi animations of beloved cartoon characters swapping heads and bodies, or Peppa Pig eating her father or drinking bleach. You could imagine Heller’s videos slipping unnoticed into these playlists. The artist was selected to represent Argentina at this year’s Biennale, where she’ll present the pavilion’s first video installation, The Importance of the Origin Will Be Imported by the Origin of the Substance (2022). The 15 videos will include the kind of characters that populated her previous works, highlighting Heller’s proclivity for surrealist narrative and world-building.

– Marko Gluhaich, Associate Editor

For additional coverage of the 59th Venice Biennale, see here.

Main image: Anders Sunna, SOAÐA, 2020, mixed media, 242 × 608 cm. Courtesy and photograph: Anders Sunna