57th Venice Biennale: the Arsenale

A first look at ‘Viva Arte Viva’ at the Arsenale

A first look at ‘Viva Arte Viva’ at the Arsenale

Over coffee yesterday, a friend suggested writing a poem composed entirely of Venice Biennale exhibition titles. With a little creative punctuation, a stanza made from show names this century would read: ‘Plateau of Humankind, Dreams and Conflicts – The Viewer’s Dictatorship. The Experience of Art, Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind: Art in the Present Tense. Making Worlds, Illuminations, The Encyclopaedic Palace, All the World’s Futures. Viva Arte Viva!’ It would be an ode to the vague and borderline meaningless. A tribute to one-size-fits-all humanist platitudes. It is a register in which every curator of the Biennale’s Arsenale and Central Pavilion exhibition – despite what previous form they may have curating shows of sharp focus and serious scholarship elsewhere – seems compelled to speak. This year’s show excels at communicating in this voice; Christine Macel’s ‘Viva Arte Viva’ is a veritable pea-souper of woolly concepts through which I struggled to make headway.

Divided into nine ‘chapters’ or ‘pavilions’ (although as the opening curatorial statement points out there is ‘no physical separation between the various pavilions which flow together like the chapters of a book’, which begs the question, why call them pavilions in the first place?) the show is ‘designed with artists, by artists and for artists, about the forms they propose, the questions they ask, the practices they develop and the ways of life they choose’ because in our period of great upheaval, the ‘role, the voice and the responsibility of the artist are more crucial than ever, within the framework of contemporary debates.’ Which sounds good to me, though let’s not exaggerate what artists can achieve when the world is on the brink of nuclear war. However Macel’s premise swiftly evaporates into curatorial nebulosity when she attempts to explain that each chapter tells ‘a story that is often discursive and at times paradoxical with detours that mirror the world’s complexities, a multiplicity of approaches and a wide variety of practices.’ So, it’s about pretty much everything then?

Each chapter, or pavilion, carries a name that could be the title of a weighty sci-fi novel by Frank Herbert or a New Age self-help book. In the Arsenale are the Pavilion of the Earth, Pavilion of the Common, Pavilion of Traditions, Pavilion of Shamans, Dionysian Pavilion, Pavilion of Colours, and the wonderfully far-out-sounding Pavilion of Time and Infinity. (Over at the Central Pavilion in the Giardini are the Pavilion of Joys and Fears and the Pavilion of Artists and Books. My colleague Evan Moffitt is covering this section of the show; please read his response in tandem with mine in order to get a fuller picture.) I wouldn’t mind the cosmic vibes these designations send out if only I could establish even the loosest, most associative connection to the artworks on display in each category. The Dionysian Pavilion must’ve been such a Dionysian experience that, like the 1960s, if I remembered it I wasn’t there, although my notes tell me it included Jeremy Shaw’s photographic explorations of altered states of consciousness and Nevin Aladağ’s charming video Traces (2015) in which cymbals, accordions and tambors are rigged up to play themselves in the streets and parks of a wintry city. The Pavilion of Traditions explains itself as a place for artists who, rather than look backwards to embrace tradition in the sense of fundamentalism and conservatism, ‘explore a more distant past, as if fired by the fever of archaeology, excavation, re-interpretation and reinvention.’ Here we find Francis Upritchard’s group of uncanny, brightly coloured alien figures; Sopheap Pich’s meditative and mute-coloured prints; an installation by Anri Sala involving a musical cylinder attached to a wallpaper-covered wall (All of a Tremble (Encounter 1), 2016), and a delicate procession of gold chains hanging from the ceiling by Leonor Antunes (…then we raise the terrain so that I could see out, 2017). All of which have distinct merits but express such wildly differing sensibilities that it leaves me wondering: what past? How distant? Excavating what? (Fundamentalism and conservatism do not necessarily derive from the pre-Enlightenment past either, as Macel’s exhibition wall-signage argues. They can be seeded in more recent periods: some of the most conservative artwork I have come across in recent years owes more to the strategies of 1970s conceptual and minimal art than it does medieval religious zealotry.)

The opening room sets the tone for the show: a set of recent coloured, geometric sculptures by Rasheed Araeen (Zero to Infinity in Venice, 2016–17) surround Juan Downey’s ring of video monitors running The Circle of Fires (1979), a video which derives from the artist’s ambitious travelogue-cum-anthropological study Video Trans America, shot during his travels across a number of Latin American countries between 1973 and ’77. The videos were made whilst Downey and his family lived in the Venezuelan Amazon, with the Yanomami people, who were invited to make and watch videos of themselves, turning inside out the conventions of ethnographic filmmaking. Throughout at least the first third of the Arsenale we encounter these sort of juxtapositions of the formal and the anthropological. The show contains a significant number of historical works, a notable proportion of which concern themselves with performance and ritual or ethnographic film. Many works exhibited make use of fabric as a material; for instance, a strikingly coloured wall of yarn globes by Sheila Hicks near the end of the show (Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands, 2016–17).

At the individual unit level of the artwork, there was much to like. Scores and videos from the 1980s to the present depicting Anna Halprin’s ‘Planetary Dance’ rituals; Charles Atlas’s The Tyranny of Consciousness (2017), a video wall depicting blazing sunsets over which we hear the voice of New York drag performer Lady Bunny talk about her life and the environment; Bonnie Ora Sherk’s Evolution of Life Frames: Past, Present, Future and Crossroads Community (The Farm) (both 2005–17) – photographs and documents tracing her longstanding work in community activism and environmental conservation. There is a fascinating section depicting ‘voyages’ and street actions by the ever-evolving Japanese performance collective The Play, who have been active since 1967 and whose work blends avant-garde theatre with social criticism. Guan Xiao’s irreverent three-channel video David (2013) documents the industry of kitsch surrounding Michelangelo’s famous statue, over which a cheeky, saccharine pop song offers thoughts on the sculpture’s everlasting popularity. Sparse and sensuous drawings by Huguette Caland are brought into three-dimensional form by three costume and mannequin works the artist made during the 1970s and 80s – her economy of draughtsmanship is breathtaking. Giorgio Griffa’s recent paintings render sets of numbers in pastel shades over a dun-coloured ground, suggestive of occult, numerological calculations. In Alicja Kwade’s austerely psychedelic installation WeltenLinie (2017), an ingeniously devised set of mirrors and bronze casts make rocks appear to be twinned or to change their surface as you move around them. Sebastian Diaz Morales’s video Pasajes IV (Passages IV, 2014) depicts a woman wandering through abandoned observatories and lighthouses in a deserted and windswept landscape. She appears to be in search of something – a person, or a path out of her isolation – but seems doomed to a perpetually fruitless journey.

In the Pavilion of Shamans is Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place, 2017). A tent, made in Neto’s signature organic style – looking less like a man-made object than a form slowly extruded from the earth – provides a Cupixawa, or social gathering place, for a group of indigenous Huni Kuin people from the Amazonian state of Acre, Brazil. Here the Huni Kuin perform healing ceremonies on visitors (the signage implies they are using the psychoactive ayahuasca, the effects of which last for many hours so it’s inadvisable to go for gelato and a gondola ride afterwards). The day of the press preview I saw the tent surrounded by people wielding cameras, crowding its entrance and jamming their lenses at the Huni Kuin wearing their traditional dress. It could have been the cover image for a 1980s cultural studies textbook, perhaps titled An Introduction to Media and Anthropology, and it seemed to embody the problem at the core of Macel’s show. Her one-size-fits-all humanism tries to show us different modes of perceiving the world but ends up being a tourist in them. In this most touristic of cities – Venice – we are presented with a tourism of consciousness, a sightseer’s guide to different ways of life that in some places comes close to fetishizing alterity as ‘a multiplicity of approaches and a wide variety of practices.’

‘The exhibition is intended as an experience,’ Macel’s statement tells us. It is ‘an extrovert movement from the self to the other, towards a common space beyond defined dimensions.’ In all honesty I have no idea what this means; all exhibitions are experiences, aren’t they? And all those experiences of seeing art are about encounters with someone or something outside one’s self. These days I for one don’t want a vague, common stance beyond defined dimensions: I want a common space that defines itself clearly in opposition to conservatism’s gaseous, insidious, shape-shifting lies. Viva Arte Viva. Yes, sure, that sounds lovely, but your point is what, exactly? I feel a poem coming on. ‘Plateau of Humankind, Dreams and Conflicts – The Viewer’s Dictatorship. The Experience of Art, Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind…’

Check back tomorrow for reports from the off-site National Pavilions and collateral exhibitions.

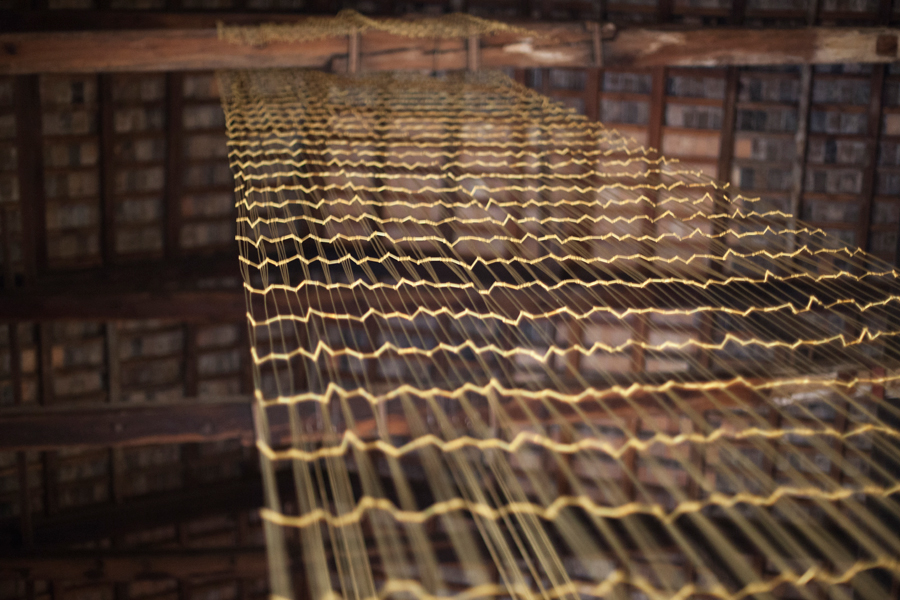

Main image: Alicja Kwade, 88 Seconds (detail), 2017, installation, 9 parts, stainless steel, dimensions variable, installation view, Arsenale, 57th Venice Biennale. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia; photograph: Italo Rondinella