Michael Andrews

Gagosian, London, UK

Gagosian, London, UK

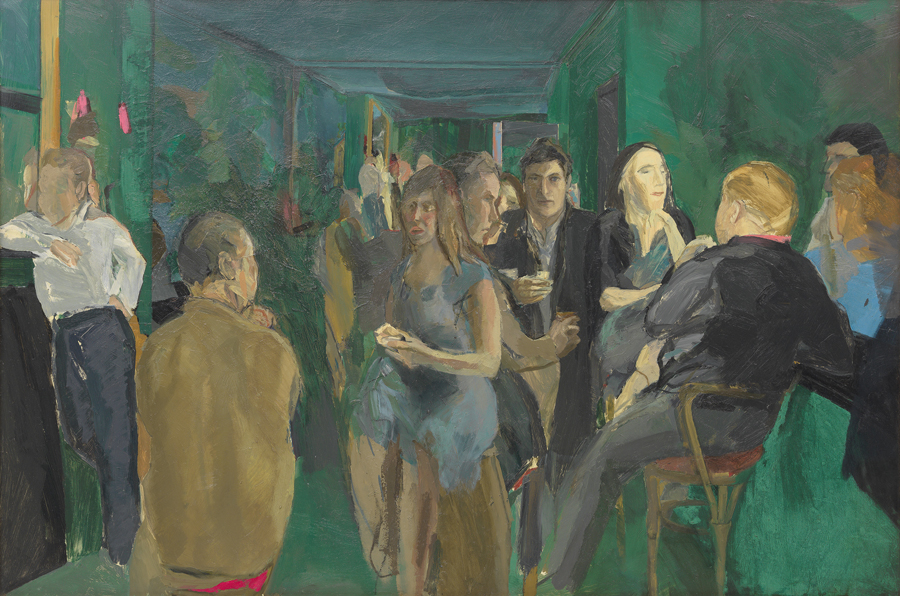

Between Michael Andrews’s death in 1995 and Gagosian’s current solo exhibition, subtitled ‘Earth, Air, Water’, his work has flown low beneath the public radar. His only retrospective to date was held at Tate Britain back in 2001 and placed a heavy emphasis on his 1960s, Edouard-Manet-meets-grimy-pop canvases of Soho’s bohemia at play. The best known of these is The Colony Room I (1962), a tense vision of the titular drinking club as an absinthe-green hell, featuring cameos by his fellow ‘School of London’ painters Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud. The former props up the bar like a bloated teddy bear; the latter meets our eyes with a glare so scalpel-sharp that it might sober us from a lifetime’s boozing.

Hung at the entrance of the Gagosian exhibition, The Colony Room I remains a thrilling painting (that lurid pink slash summoning up Bacon’s shirt collar!). However, in the context of the later, Zen Buddhism-inspired land-, sky- and seascapes that structure much of ‘Earth, Air, Water’, it feels like a cramped antechamber to a much more ambitious project: to face the vast indifference of the universe and find within it not only beauty, but also peace. This hasn’t always been my response to Andrews’s post-1960s work. Writing about his Tate retrospective in frieze 16 years ago, I lamented his decision to abandon painting cocktail parties and creeping existential dread for serene, seldom-peopled vistas, which I claimed (with the kind of unwarranted cockiness only a 23 year old can muster) had ‘the dulled edge of a post-rehab rock star’. Looking at them now, with their near-frictionless, spray-gunned acrylics, their gently suffusing stains, they have an almost psychedelic clarity. It’s my age, isn’t it? You’re going to tell me it’s my age.

‘As it seems, so it is’. This was Andrews’s painterly principle, which meant embracing not only the contingency of his perceptions, but also the fact that they were nothing more than the weather patterns of his mind. The hinge between his party pictures and his elemental works was the ‘Lights’ series (1970–75), in which the self is imagined as a hot air balloon (a take on R.D. Laing’s idea of the ‘skin encapsulated ego’), drifting over London’s bridges or kissing the sands of empty beaches with its shadow. Lights I: Out of Doors (1970) is painted from the perspective of the balloon’s basket. Beneath us, hovering far above rolling English hills, we see another balloon, its white form trembling between solid and liquid, like a creamy burrata or a blob of acrylic paint on a palette. Clearly, something was about to give.

Give it does. From the mid-1970s on, Andrews’s is an art of both limpid naturalism and quiet ecstasies. The self becomes a channel for a world in constant flux, and time appears to exist only as permanent now. His watercolour A Pond: Spring (1977) might have been made by simply blotting his paper on the surface of an algae-speckled pool, while the Australian Outback’s ancient rocks appear, in Valley of the Winds Katajuta (The Olgas) (1985–86), to be formed from freshly set blancmange. The dark humour of his party pictures reappears in School IV: Barracuda Under Skipjack Tuna (1978). Here, piscine predators and their prey share the same impossibly blue waters. Give them each a stiff drink and we’d be back in the Colony Room.

In Andrews’s final canvas, the bleakly beautiful Thames Painting: The Estuary (1994–95), speckles of that river’s silt have found their way into his pigment, while a gaggle of Victorian gentlemen fish on its foreshore. We might think of James McNeill Whistler, here – the great mudlark of British painting – or we might simply think of where Andrews’s Styx-like Thames leads.

Main image: Michael Andrews, School IV: Barracuda under Skipjack Tuna, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 1.8 × 1.8 m. Courtesy: James Hyman Gallery, London © The Estate of Michael Andrews