Nick Mauss: Eras and Eros at the Whitney

In New York, the artist untangles the intertwined histories of ballet, avant-garde visual art and clandestine gay life in mid-century America

In New York, the artist untangles the intertwined histories of ballet, avant-garde visual art and clandestine gay life in mid-century America

A sailor suit made of organza hangs at the entrance to Nick Mauss’s solo exhibition ‘Transmissions’. Installed in the Whitney Museum of American Art, it’s a re-fabrication of a costume designed by artist Paul Cadmus for the 1950 ballet Filling Station, during which dancer Jacques D’Amboise did jetés while dressed in the translucent fabric. Without a wearer, the costume looks ethereal and ghostly. Still, I thought I saw it swaying gently in the breeze – an illusion produced by the bronze statuette below it, of a kneeling dancer by the artist Elie Nadelman made around 1916, which gently rotates on a motorized plinth.

This confusion of motion with stillness is one of many graceful ways Mauss, a visual artist, animates an important but abbreviated period in modern ballet history for his first institutional show in the US. Between the 1930s to the 1950s, a distinctly American style of ballet emerged in New York, amid intense collaborations between critics, choreographers, dancers and visual artists. The work in Mauss’s exhibition feels surprisingly contemporary, both for its experimental quality and for its overt, exuberant expressions of homosexuality from an age in which it was rarely allowed to be made public. In addition to original works inspired by archival research, such as a 53-panelled enamelled mirror painted using a reverse glass painting technique popular in the 1930s called verre églomisé, Mauss sourced objects from the Whitney’s collection, the Kinsey Institute for Sex, Gender and Reproduction and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library – uncovering the era’s social, romantic and artistic relationships as he went.

The legacy of the collaborations between the visual arts and choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer are much better-known than the exchanges between the visual arts and ballet. Mauss writes that he was surprised not to know of 20th-century ballet figures such as Christian Bérard, a French painter and designer of ballet sets who was an important artist during his lifetime but relatively unknown today. It seems as though Mauss found something engrossingly familiar in the artists of these period, as though they are relatives he never got a chance to meet. Some of the photographs, paintings, sketches, slide projections and sculptures – such as a Pavel Tchelitchew costume design for the ballet Variations on Euclid, (c.1932), a graphite sketch by the artist Elie Nadelman, Head of a Woman, (c. 1925) and a 1931 Walker Evans photograph of the famous ballet director, Lincoln Kirstein (Without Hat) – are arranged along the gallery walls in scattershot fashion, like family portraits hung along a hallway. Mauss is as concerned with history’s absences as he is with its remnants: in one wall text, he writes that while researching this period, he realized that he might have known much more about the era if the intervening generation hadn’t been decimated by AIDS.

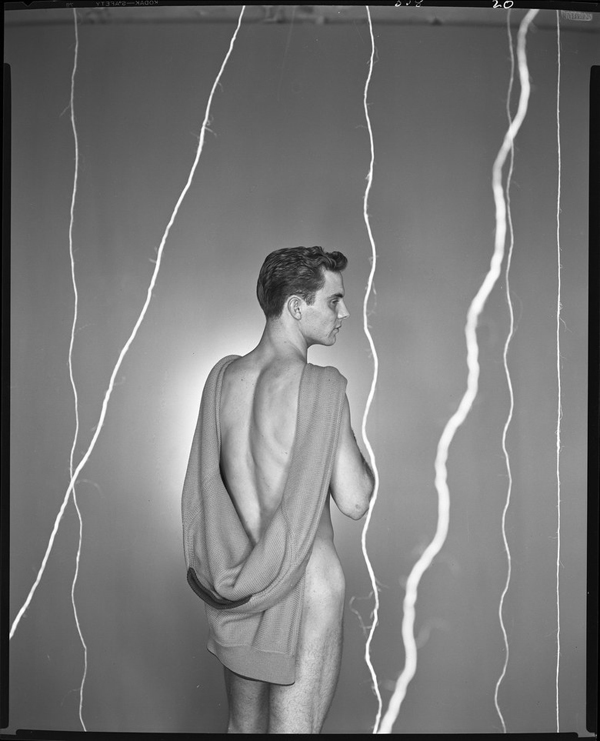

At the front of the gallery, a group of 16 silver gelatine prints by artist George Platt Lynes – who became American Ballet Theater’s official photographer in 1934 – reveal the exhibition’s most explicit interchange between a clandestine visual language of homosexual erotics and the cool formalism of early ballet photography. Elegantly-posed choreographers and dancers alternate with nude portraits of ballet dancers and models that Lynes shot after hours, sometimes repurposing the same sets he used for ballet photographs and commercial work for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. One man hangs gently upside down, like a piece of fruit on a low-hanging branch; another curls into a ball, revealing an anus framed in dark hair. The selection of photographs provides an introduction to some characters that crop up repeatedly in the exhibition, such as Paul Cadmus (who designed the organza men’s sailor suit, another photograph of which is found inside) and Jared French, who together with his wife Margaret Hoening French and Cadmus, formed the photography collective PaJaMa. In Lynes’s 1937 photograph, they appear in a pose both geometric and tender, bottomless and draped over a set of stairs.

Generous exhibition space is given to a piece of grey marley flooring, where a group of four dancers perform collaboratively-generated ballet in the gallery each day. Mauss loosened the conventional understanding of ballet’s present-day lineage by selecting a group of 16 dancers with varying relationships to the form, from professional ballerinas to modern dancers. Together they developed gestures and steps inspired by archival rehearsal footage and photographs – some of which is on display in the exhibition, some coming from Mauss’s larger body of research. In another subtle transposition of time, the dancers move through stately poses costumed in muted colours, while a nearby slideshow of photographs of fancifully-dressed dancers taken by the seminal ballet critic and photographer Carl Van Vechten between the 1940s and ’60s flashes in bright colours.

One dancer, Maggie Cloud, told me later that although they hailed from different parts of the dance world, many of the dancers already knew each other. On the day I visited, the four performers occasionally laughed while warming up or going over the steps in a partner duet. When they began a quartet jumping section, the museumgoers around them surrendered to the compulsory modern-day ritual of capturing every minute of their performance – instantly generating a trove of documentary images of intimacies and gestures that, despite the performance’s public nature, I wondered if anyone else would ever see. I asked one especially enthusiastic photographer what he planned do with the images. He told me he was an amateur ceramicist who rarely got this close to dance. ‘I’ll probably put some up on Facebook so my friends can see them’, he said. ‘Then I’ll put the rest away, until I feel like getting them out and looking at them again.’

Nick Mauss, ‘Transmissions’, 2018, runs at the Whitney Museum of American Art until 14 May.