Rebecca Ackroyd Takes Femininity to the Battlefield

At Peres Projects, Berlin, the artist’s uncanny paintings and sculptures speak to how female sexuality can be used as a weapon

At Peres Projects, Berlin, the artist’s uncanny paintings and sculptures speak to how female sexuality can be used as a weapon

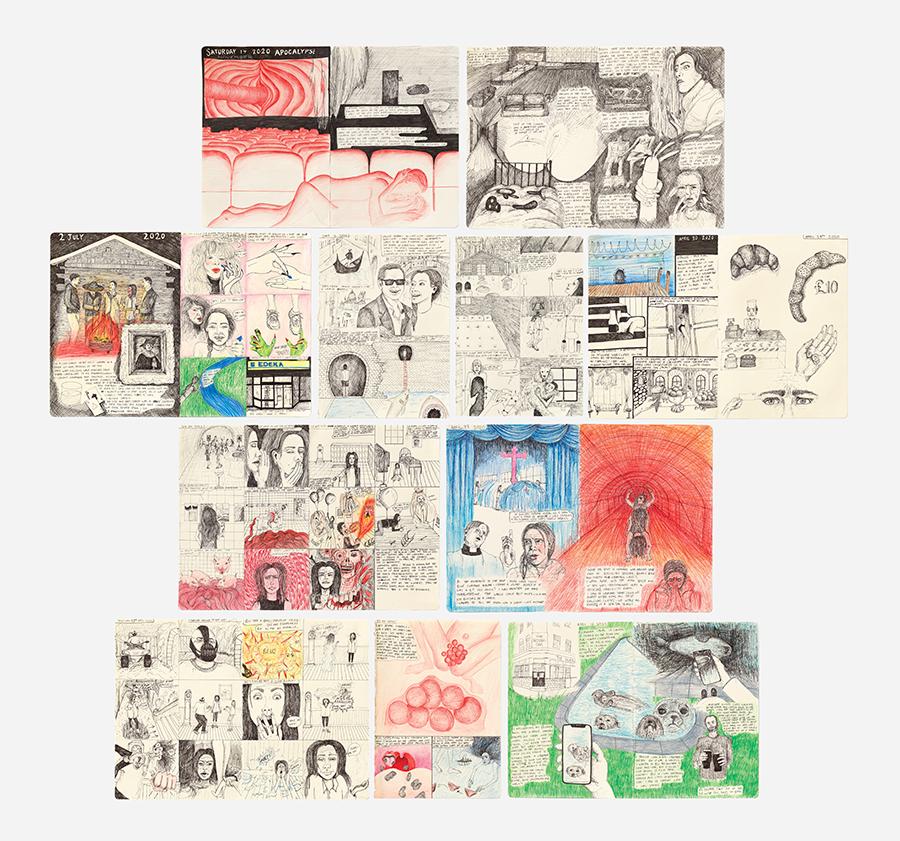

Since the beginning of the pandemic, multiple reputable media outlets have reported on a global increase in people experiencing vivid and unusual dreams. Based on ‘100mph’, Rebecca Ackroyd’s second solo exhibition at Peres Projects, I’d wager that this nocturnal shift has also happened to the Berlin-based artist. Nowhere is this as clear as in the show’s titular work, which depicts some of Ackroyd’s lockdown dreams in a series of pen and coloured pencil drawings on paper. With scenes ranging from hotel orgies to an artist being fed into a meat grinder, they make my own reoccurring nightmare of crumbling teeth look positively banal.

Just as 100mph (all works 2020) is full of symbolism and metaphor, so too are the further 26 paintings and sculptures in this extensive exhibition, many of which feature unusual juxtapositions that border on the uncanny. In Tonguing the Fence, for instance, an epoxy resin cast of the lower half of a female body in boots and fishnet tights sits on small steel chair made of a hubcap. The composition is given a strange twist through the placement in the woman’s hands of a dollhouse, whose tiny door is where the pubis should be – cheekily suggesting that home is where the vagina is.

This sense of the uncanny increases the longer you spend not only with the works but also in the rooms themselves, which have been adapted through a series of temporary structures wrapped in semi-opaque dust sheets. Adding extra wall space as well as covering all of the windows, these modifications create an overall impression of being trapped in a space where even things that feel familiar aren’t what they seem. In one corner of the gallery, the floor is partly covered with overlapping layers of old-fashioned patterned carpet. In the middle sits Same Roof of Similar, a small eerily characterless model of a house. As I moved closer to get a better look, I tripped on the carpet folds – the jolt reminding me of that moment of lucidity you experience in an oneiric state when one slightly amiss detail makes you realize you must be dreaming.

Associations between female bodies and urban environments can be traced in a number of pastel drawings of drainage systems and air vents. Painted in nude shades against a blood-red background, these works – Spine, Fillet, Fingers Deep and Breath Taking – recall the human skeleton and, to my mind, the intriguing torsos of the late Chicago Imagists painter Christina Ramberg (e.g., Willful Excess, 1977). Like Ramberg, Ackroyd has a penchant for hair, from long red waves (In all my Fear or Glory) to sets of eyelashes as thick and glossy as a horse’s mane (Weight of the World, Splinter Cell and Familiar Ground). In these paintings, hair becomes a symbol for a kind of hyper-femininity, which, like the Instagram fad for fake ‘stiletto’ nails sharpened to a point, oscillates uncomfortably between alluring and threatening.

The idea of a woman wearing her femininity as battle armour isn’t new; as Donatella Versace said in an interview with Glamour in 2010: ‘A well-cut dress can help you reach your goals. It’s a weapon.’ In Ackroyd’s hands, however, this tired neoliberal concept is stretched until the elastic gives way. Female sexuality turns monstrous in 1,000,000 Eggs, for example, which depicts a figure clad in fishnet stockings with a provocative hand resting on her emerald green stomach, as well as in Side Saddle, a dark and angsty drawing of what could be a ponytail or a pubis morphing into a thin stream of blood. While Versace sees the potential for clothing to threaten, Ackroyd seems to suggest that it is the shapeshifting potential of femininity itself that can be wielded like a sword.

Rebecca Ackroyd, ‘100mph’ is on view at Peres Project, Berlin, until 5 March 2021.

Main image: Rebecca Ackroyd, Drip Feed (detail), 2020, Gguache, soft pastel on Somerset satin paper, 29 × 37 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Peres Projects, Berlin; photograph: Matthias Kolb