Why Frank Walter Can’t Be Categorised

At MMK Frankfurt, a retrospective housed in a group exhibition mirrors the artist's rejection of conventional classifications

At MMK Frankfurt, a retrospective housed in a group exhibition mirrors the artist's rejection of conventional classifications

It is impossible not to read Frank Walter’s biography into his art. Born in 1926 in Antigua – a West Indian island whose people were repressed and murdered under British colonial rule from the 1600s, only gaining full independence in 1981 – Walter was a descendent of both plantation owners and slaves. In the 1950s, he travelled for a decade around Britain and West Germany (home of his ancestors) via France, Switzerland, Italy and Venezuela. During his time in northern England and the Rhineland, he worked as a miner, in a boatyard and at a lamp factory. It was then that he began to paint the abstract works which are at the centre of his current exhibition, ‘Frank Walter: A Retrospective’, at Frankfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK).

The breadth and volume of Walter’s production is staggering: he created more than 5,000 paintings on wood, Masonite, cardboard, paper and linoleum with watercolour, crayon, pencil, shellac and oil paint; he carved more than 600 wooden sculptures and authored more than 50,000 pages of poetry, political essays and prose. Comprising more than 400 paintings, sculptures and texts, this exhibition also puts Walter’s work into conversation with pieces by 12 contemporary artists – including John Akomfrah, Kader Attia, Julien Creuzet, Isaac Julien and Howardena Pindell – making it a retrospective housed inside a group show.

Denying any neat classification, most of Walter’s paintings are undated and untitled. The abstract works – some of the few to be given titles, such as Wavelengths of Light and Heat (1960) and Intergalactic Botany (undated) – make evident the artist’s interest in astrology, celestial spectacles, physics, sci-fi and fantasy. Appearing simultaneously medieval, avant-garde and contemporary, they happily conjure up the fourth dimension, chemical transformations and the dance of molecules. In Psycho Geometrics (undated), for instance, five brightly coloured circles on a black background enclose five-pointed stars – comprised of graphic shapes in orange, yellow, petrol blue, turquoise, red and white – reminiscent of the Mazdanian colour wheels in the work by Bauhaus teacher Johannes Itten. Hypnosis (undated) depicts a giant Cyclops eye with a red pupil and ochre lid surrounded by grey, blue and brown concentric ovals. Many of these works reflect on psychic experiences and the potential to heal and control the mind through abstraction. In an unpublished manuscript, quoted in the catalogue, Walter writes of his brain working on a ‘hist-psycho-psychic frequency’ and described the frequent hallucinations and dissociative visual experiences from which he suffered in terms of ‘television eyes’, whereby he would imagine scenes playing before him as if on screen.

Walter painted mostly on cardboard taken from the discarded packaging that once contained Polaroid film, records and soap powder – a material at odds with the crisp geometric forms that characterize his work. Unlike modernism’s traditional canvases, these works’ torn edges and corrugated ridges transform them into ephemeral objects. Walter’s use of mass-produced and domestic packaging speaks to a more profound dialectic at play in his art: the everyday realism of West Indian vernacular life found in his painted portraits, landscapes and botanical studies versus his representations of the psychic, surreal and abstract. This exhibition, with its focus on thematic groups, including the commercial Polaroid portraits Walter produced in his roadside photo-studio – nicely foregrounds these dualisms.

Throughout the show, the convention of hanging paintings on the main gallery walls is rejected. Instead, these are painted in bold colours from Walter’s palette, while his works are displayed on partition walls, creating the effect of a series of installations or environments. This corresponds to the presentation of the pieces by other artists, many of which are videos and installations. The latter work to great effect, haunting, confronting and muddying the subjects and life experiences central to Walter’s practice.

Many voices speak for Walter throughout the show: political philosopher Frantz Fanon, art historian Kobena Mercer and historian Paul Gilroy are all quoted by Julien in his film Territories (1984), which explores London’s Notting Hill Carnival, the Caribbean community who organize it and the strange overlaps between masquerade and protest. In contrast, Creuzet’s video Mon Corps Carcasse / Se Casse, Casse, Casse, Casse (My Body Is Falling Apart, 2019), extends Walter’s work into the present by focusing on neoliberal models of colonial power. Creuzet’s computer-generated animation depicts a pulsating black banana flexing and spewing out blood cells and disease like fireworks. The fruit throbs in neon shades, morphing into sexual organs orbited by crashing aeroplanes. The work reflects on the deadly consequences of using chlordecone, a non-biodegradable pesticide, in banana plantations on the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, which have the highest prostate and uterine cancer rates in the world.

Despite the many interrogations of colonial power structures and racism central to the pieces by the 12 accompanying artists, which speak to Walter’s practice and prevent it from being too easily historicized, the artist’s own biography and politics at times complicate this curatorial frame. Surprisingly, Walter identified as German and with Germanic culture, but his unpublished notes praise his forefathers in worrying tones – he proclaims ‘Black Germans’ to be ‘the richest and most powerful of the Aryans’ – and, at times, his writings also foster a distinct anti-Semitism towards the Jewish factory owners in England, whom he felt had mistreated him during his time there. If the political experiences of his racist abuse in Britain and Germany and the bigger narratives of slavery, colonialism and postcolonialism are brought into sharper focus with the many dialogues staged, often the contemporary works are also in a tug of war with the fantastical, apolitical and even reactionary inner life and psychic traumas so central to Walter’s art.

Walter created many imaginary and obscure alter egos, such as 7th Prince of the West Indies, Lord of Follies and the Ding-a-Ding-Nook, which, despite sounding surreal, all referenced plantations and properties once owned by the Walter family in the 18th century. He also became briefly obsessed with the British royal family: writing in his poem ‘Odin, God of the Wind, God of the Sea’ (c. 1960), that Princess Margaret should be his bride and constructing elaborate fictive genealogies, some of which connected him to Charles II of England. In the accompanying catalogue, we also learn that Walter suffered a nervous breakdown in 1965 on a boat journey to Britain and, whilst denied access to the UK, that he hallucinated about Neptune and sea monsters during his incarceration on the ship. His substantial series of small, round paintings – which fill one large upstairs gallery – possibly relate to this experience of gazing out of portholes and maritime psychosis. It is in this psychic and scarred landscape, where autobiography and aesthetics meet, that Walter’s work sits. For example, the many wooden sculptures he produced were originally created not as art, but as idols to protect him, and were carefully arranged around his home.

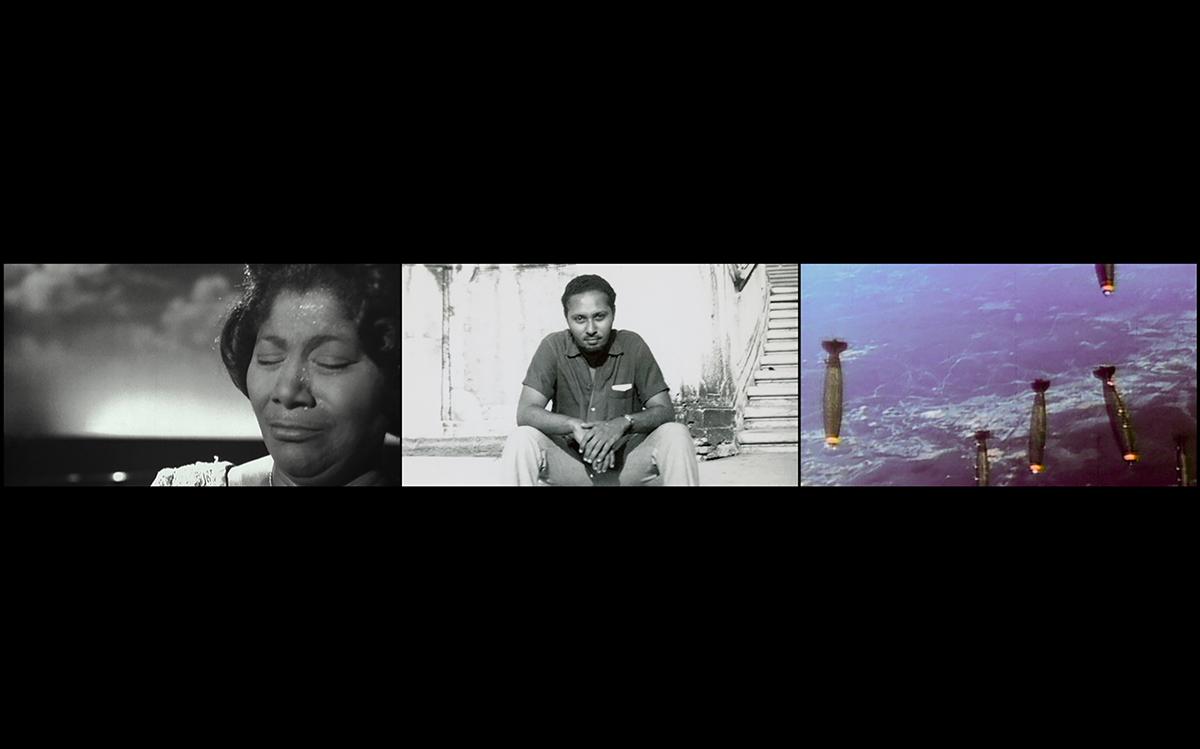

Arguably the most successful dialogue staged in the show is between Walter’s abstract work and Akomfrah’s video The Unfinished Conversation (2012). An homage to the sociologist and founder of cultural studies, Stuart Hall, its three screens shift between colour and black and white, between archival documentary and cinema. Biography blends into politics, as footage of the Caribbean landscape meets the austere working-class streets of 1950s Britain. The cosmic, the natural and the familial collide, with shots of the moon and astronauts juxtaposed with those of Hall’s baby and sunny beach holidays – neatly foregrounding the same complex triangle of issues within Walter’s work and offering a nuanced but conflicted notion of hybrid identity closest to the artist’s own.

'Frank Walter: A Retrospective' is on view at MMK Frankfurt until 14 November 2020

Main image: Frank Walter, Untitled, undated, oil on corrugated cardboard, 12.6 × 22.4 cm. Courtesy: the Estate of Frank Walter; photograph: Axel Schneider