Women Artists and the Looking Glass

Jennifer Higgie on how the mirror’s mass production changed the course of art history – and liberated women artists

Jennifer Higgie on how the mirror’s mass production changed the course of art history – and liberated women artists

Unless you’re intent on creating an imaginative world, to paint a self-portrait in the most

literal sense – an image of what you look like – you need to be able to see yourself. But seeing yourself isn’t a straightforward activity: to look into a mirror can result in as much deceit as understanding. The mirror tells the truth as often as the person looking into it lies – and its invention opened up new ways of looking at, thinking about and representing your own

face and body.

Mirrors, as we know them, are a relatively modern invention; until the mid-19th century they were a luxury item. The earliest ones, which were discovered in Çatal Hüyük, in modern-day Turkey, date from around 6,200 BCE and are made from highly polished obsidian: looking into one is like gazing into black water. (This is apt: still, dark water, as the myth of Narcissus looking at his own reflection in a pool attests, could be considered the first mirror.) The oldest copper mirrors are from Iran and date from around 4,000 BCE; not long after, the Ancient Egyptians began making them, too; the Romans crafted mirrors from blown glass with lead backing. By 1,000 BCE, mirrors – in various shapes, from different materials and for different ends – were made throughout the world: by the Etruscans, the Greeks and the Romans, in Siberia, China and Japan. In Central and South America, the Aztec, Inca, Maya and Olmec civilizations all used them, for both personal and spiritual aims; in many cultures, mirrors were believed to be magical objects that granted access to supernatural knowledge. During Britain’s Iron Age – from about 800 BCE to the Roman invasion of 49 CE – mirrors were made from bronze and iron. When glass-blowing was invented in the 14th century, hand-held convex mirrors became popular. In 1438, Johannes Gutenberg opened a mirror-making business in Strasbourg; six years later, he invented the printing press. There’s a symbolic connection between the two: both allow access to other dimensions, reflect the world back on itself and stimulate the expansion of knowledge.

In a wonderful marriage of the looking glass and the printing press, by 1500 more than 350 European books had titles that referenced mirrors. In France, women of the court began to wear small mirrors attached to their waists by delicate chains: a fashion that was considered by some commentators to be so vain as to be depraved. In the 16th century, the island of Murano near Venice, long known for its glassware, became the European centre for mirror manufacture. To put the ensuing craze for mirrors into perspective: in the early 16th century, an elaborate Venetian mirror was more valuable than a painting by one of the giants of the Renaissance, Raphael, while, at the end of the 17th century, in France, the Countess of Fiesque swapped a piece of land for a mirror. In 1684, the Hall of Mirrors was completed at the Palace of Versailles: it comprised more than 300 panes of mirrored glass, so that royalty could see their glory reflected seemingly to infinity. The Hall’s fame spread – and was copied – throughout Europe.

The first known oil painting featuring a mirror – and arguably the most famous – is Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434), which now hangs in London’s National Gallery. (It’s also the first double portrait of people in a domestic setting.) It features a convex mirror in which you can see a tiny reflection of the entire room, the backs of the couple who occupy it and two small figures standing in the doorway: quite possibly one of them is a minuscule portrait of the artist. Van Eyck wasn’t alone in his fascination with looking glasses. Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with mirrors, both as objects and metaphors. He observed in his notebooks that ‘the mind of the painter should be like a mirror which always takes the colour of the thing it reflects and which is filled by as many images as there are things placed before it’. One of the greatest self-portraitists, Albrecht Dürer, confessed that his paintings were ‘made out of a mirror’, Giorgio Vasari distinguishes between self-portraits painted ‘alla sfera’ (with a convex mirror about the size of a saucer) and ‘allo specchio’ (either flat or convex but more likely to be made from metal). It’s fair to say that developments in mirror-making were directly reflected in developments in picture-making.

Despite their popularity, however, for centuries mirrors were difficult to make, expensive and – due to the mercury amalgam with which the glass was backed – poisonous. It wasn’t until 1835 that the German chemist Justus von Liebig invented a process that allowed mirrors to be mass-produced.

What is rarely mentioned in cultural histories of the mirror is how liberating it was for female painters. For millennia, for reasons of propriety, women were forbidden from depicting themselves or anyone else naked while men could paint and sculpt however they saw fit. (The Renaissance artist Lavinia Fontana is an early exception to the rule; she included naked figures in her large-scale religious and mythological works and is considered the first woman to do so. Artemisia Gentileschi soon followed suit.) Easier access to mirrors meant that, for the first time, a woman’s exclusion from life classes at art academies didn’t stop her from painting figures. Now, with the aid of a looking glass, she had a willing model, and one who was freely available around the clock: herself.

Given the formidable restrictions placed in their way, it’s understandable that, throughout history, women have made fewer works of art than men. (My focus here is women in the European tradition. Women’s creativity is central to many Indigenous cultures around the world.) But if you took some art-historical accounts as gospel, you’d be forgiven for thinking that women only started making art after World War II – and not many of them, at that.

It’s important, though, to stress that the existence of pre-modern women artists was not suddenly and miraculously discovered in the mid-to-late 20th century. Although scarce, records of women’s creativity in the fine arts have, in fact, existed since the beginnings of written history. The Roman historian Pliny the Elder – who was to die as a result of the eruption of the volcano Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii in 79 CE – even asserted that the art of painting originated with a woman. In his Natural History, he recounts how the sculptor Butades of Corinth discovered portraiture around 650 BCE thanks to his daughter, Kora of Sicyon, ‘who, being deeply in love with a young man about to depart on a long journey, traced the profile of his face, as thrown upon the wall by the light of the lamp’. According to this tale, her father then filled in the outlines with clay and modelled the features of the young suitor – and so created the first portrait as a sculptural relief.

The story endured. In the 18th and 19th centuries, depictions of Kora tracing the outlines of her lover’s shadow – often titled The Origin of Painting or The Art of Painting – became popular. But Kora is not the only woman Pliny mentions; he cites six other women artists from antiquity: Aristarete, Calypso, Irene, Olympia, Timarete and Iaia of Cyzicus; the last was a Roman painter from the first century BCE who, according to the historian, ‘remained single all her life’ and rendered ‘a portrait of herself, executed with the aid of a mirror’ – the earliest mention of a self-portrait made with a mirror. In the late 12th or early 13th century, the German illuminator Claricia depicted herself in a wide-sleeved dress swinging from the letter ‘Q’ like a trapeze artist. Although she’s airborne, any sense of danger is undermined by her very evident sense of humour. Her name, in tiny letters, frames her face. It’s a rare, exuberant image of a medieval woman thumbing her nose at decorum. You can almost hear the sound of her distant laughter echoing across the centuries.

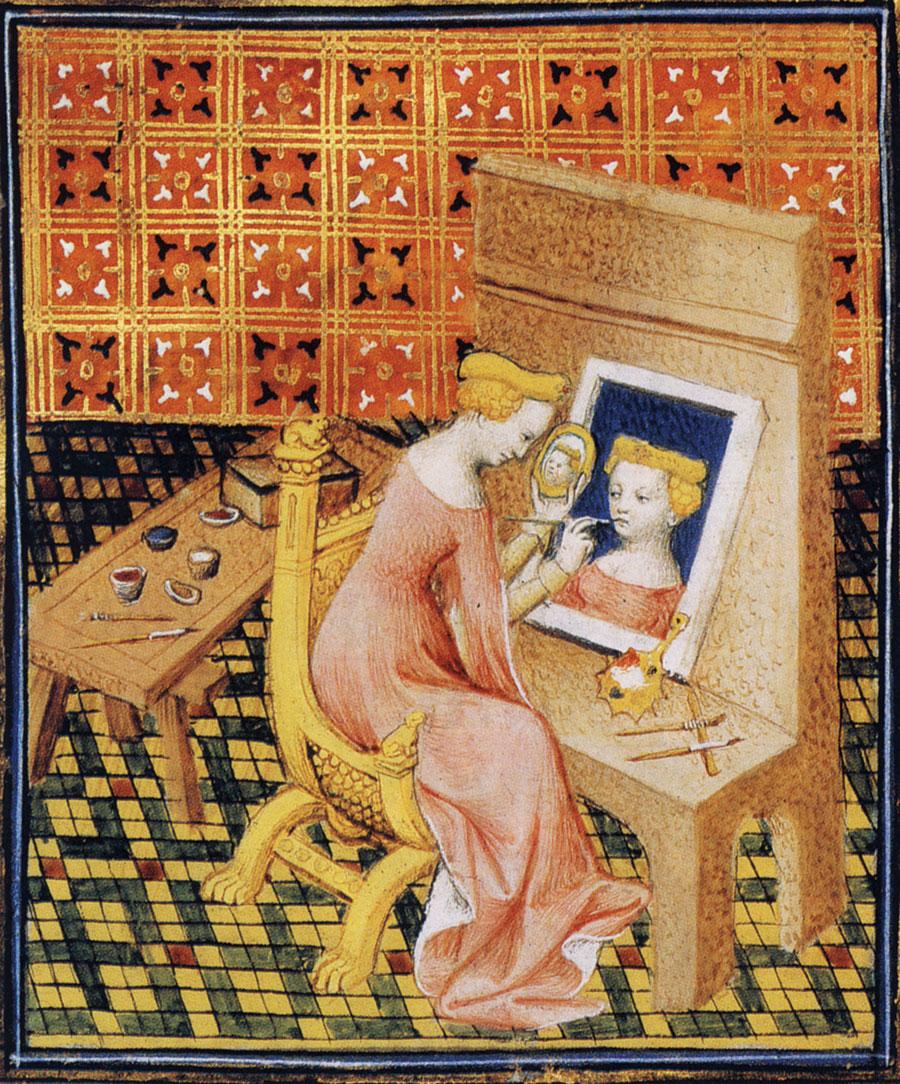

In the 14th century, some of the women mentioned by Pliny resurface in the Florentine historian Giovanni Boccaccio’s collection of 106 historical and mythical biographies, De Mulieribus Claris (Concerning Famous Women), the first book in Western literature devoted to the achievements of women, which also includes the earliest representations of a woman painting her self-portrait. A French version of the book from 1402 includes a beautiful ink-and-colour parchment illustration, Marcia Painting her Self-Portrait.

The unknown artist has depicted Marcia – who Boccaccio possibly based on Iaia of Cyzicus – seated at a desk, a convex mirror in her left hand; her right hand holds a brush, with which she is painting the lips of her self-portrait, as if to stress that Marcia’s powers of articulation resided in paint, not spoken words. A small palette, which at first glance looks like another hand mirror, is placed to her right, next to two brushes. The image is rendered in patterns of warm ochres, reds and yellows. This tiny image is, remarkably, a triple portrait: we see Marcia at the easel, represented in her self-portrait and reflected in her mirror. That it was created in 1404, around 30 years or so before Van Eyck painted what is considered to be the first self-portrait in oils, makes it even more original. However, despite the positive focus of Boccaccio’s book – he believes, to a certain extent, that women should be allowed to choose the direction of their lives – the historian was obviously unconvinced about the potential of women artists. With staggering pomposity, he opines that ‘the art of painting is mostly alien to the feminine mind and cannot be attained without that great intellectual concentration which women, as a rule, are very slow to acquire’.

The City of Ladies

We can only imagine how this might have made female readers feel. One told us. Christine de Pizan, who was born around 1364, was a French poet, scholar, philosopher and writer of what today we might call experimental fiction. After the death of her husband in 1390, she became the first

woman in Western letters to support herself, her three children and her mother by writing. Her wildly original defence of women’s talents and potential, The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) (she also wrote a sequel: The Treasure of the City of Ladies) embodies the medieval literary tradition of the dream vision, which was popularized by Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy. Because of the very nature of dreams – absurd, non-linear, fantastical – writers used them as a springboard to explore ideas free from the constraints of convention and logic. The Book of the City of Ladies opens with the narrator wondering ‘why on earth it was that so many men, both clerks and others, said, and continue to say and write such damning things about women and their ways’. Pondering the question, she slumbers ‘sunk in unhappy thoughts’, but is startled awake by a beam of light, which reveals itself as three virtuous women: Reason, Rectitude and Justice. They have come to comfort Christine and tell her that ‘those who speak ill of women do more harm to themselves than they do to the actual women they slander’. They explain that she has been chosen to construct a walled city, ‘to ensure that, in future, all worthy ladies and valiant women are protected from those who attack them. The female sex has been left defenceless for a long time now, like an orchard without

a wall, and bereft of a champion to take up arms in order to protect it.’

hey propose that only ‘ladies who are of good reputation and worthy of praise’ will be allowed through the city’s gates. After much discussion, they choose around 200 women from history – ironically, many of them possibly sourced from Boccaccio’s Concerning Famous Women – who will lead by example. They include warriors, nuns, priestesses, saints, scholars, inventors – and artists: Irene, the painter from Ancient Greece mentioned by Pliny whose skills surpassed all others; her compatriot Thamaris, whose ‘brilliance has not been forgotten’; and the aforementioned Marcia, who painted herself with the aid of a mirror, and whose talent ‘outstripped all men’. Christine is also vocal in her praise of her contemporary, Anastasia, who she describes as ‘so good at painting decorative borders and background landscapes for miniatures that there is no craftsman who can match her in the whole of Paris, even though that’s where the finest in the world can be found’. Reason responds drily: ‘I can well believe it, my dear Christine. Anyone who wanted could cite plentiful examples of exceptional women in the world today: it’s simply a matter of looking for them.’ None of Anastasia’s work has survived – or, if it has, it is not attributed to her

Main image: Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, 1638–39, oil on canvas, 97 × 74 cm. Courtesy: Royal Collection Trust/ © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

This article first appeared in frieze issue 218 with the headline ‘Look Closely’.