Yuko Mohri Brings Her Kinetic Installations to Life

In the Tokyo-based artist's works, everyday objects are animated by electric motors and chance elements

In the Tokyo-based artist's works, everyday objects are animated by electric motors and chance elements

In How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human (2013), anthropologist Eduardo Kohn argues that a forest is a living semiotic chain, using the example of a hunt in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Spotting a monkey hiding in the canopy, the hunters chop down a nearby tree, sending it crashing to the ground. The startled monkey interprets that sound as a sign of approaching danger and flees from its hiding place, giving the hunters a clear shot at their target. A sophisticated interspecies exchange has taken place, mediated by the forest.

Kohn’s vision of a living semiotic chain is an apt entry point for thinking about the work of Tokyo-based artist Yuko Mohri. Equal parts humorous and spooky, Mohri’s kinetic installations typically feature networked assemblages of everyday objects – from spoons and forks to balloons, light bulbs, blinds and musical instruments – animated by motors powered by ad hoc electric circuits that are, in turn, governed by chance elements, such as air currents, gravity or magnetism.

Mohri has a background in sound practices: she was in a hardcore band, Sisforsound, while at university and she collaborates with musicians like Seiichi Yamamoto from the Boredoms and Otomo Yoshihide. Since the objects in her installations make sounds when they move, it’s tempting to describe her as a sound artist. But sound, for Mohri, like the crashing tree in the forest, is not so much an end in itself as it is an index of other invisible forces at work.

This is apparent in one of her earliest major works, I/O (2011–ongoing), first produced for the Japan Foundation-sponsored exhibition ‘Alternating Currents: Japanese Art after March 2011’ at Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. In this installation, which continues evolving across different contexts, large rolls of printer paper unspool from apparatuses suspended from the ceiling. Moving in a loop, the paper grazes the floor and then makes its way upward again, accumulating dust and other particles on its surface as it does so. Sensors in the apparatuses then read those accretions as a score for activating assemblages scattered around the room, sending a feather duster attached to a motor into outbursts at one moment and triggering the wheezy exhalation of an old organ the next.

Mohri’s works also take on an aspect of psychogeography, as with Circus in the Ground (2014), produced for the Sapporo International Art Festival on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido. This site-specific commission made use of a pavilion built for the Meiji emperor’s 1881 tour of the area; the pavilion is located near a spring once used by the indigenous Ainu people, who were displaced by Japanese settlers during Meiji-era imperialist expansion (1868–1912). Referencing associations among the Ainu words for ‘sense’, ‘sound’ and ‘circle’, Mohri’s installation, in which the electrical circuit is controlled by a ring of manically wavering compass needles, points to repressed tensions underlying the rationalist grid upon which modern Sapporo was constructed.

The artist’s project for this year’s Gwangju Biennale will adapt I/O – the title of which refers both to Perth’s location on the Indian Ocean and the acronym for input/output – for one of the glass pavilions at Horanggasy Artpolygon, a community art space situated on Yangnim Mountain, associated with premodern sky burials, American evangelization and local resistance to Japanese colonization. Here, Mohri will use Gwangju-born writer Han Kang’s elegiac novel The White Book (2016), which was shortlisted for the 2018 Man Booker International Prize and which explores the unrealized life of the narrator’s older sibling who died two hours after birth, as a source for manifesting unwritten histories and unheard voices. Seeking to amplify the resonances of the site, Mohri envisions both sounds and objects spilling out from the space – originally built for an American missionary – and flowing into the surrounding garden.

In a Japanese art-historical context, Mohri’s practice lies as much on a continuum with the Mono-ha artist Kishio Suga, whose precarious configurations of lumber, stones, sand, water and other materials decentre the human subject by revealing how relations of interdependency generate space, as it does with pioneering intermedia artists like Group Ongaku, who employed everything from kitchen utensils to electrical appliances and radio broadcasts in their improvised performances. Depositing visitors into a forest-like environment – or, in Kohn’s words, ‘an emergent and expanding multilayered cacophonous web of mutually constitutive, living and growing thoughts’ – Mohri’s installations tease apart the apparent uniformity of our built spaces. In doing so, they offer insight into how our own selves are permeated by and enter into assemblages with other forms of being.

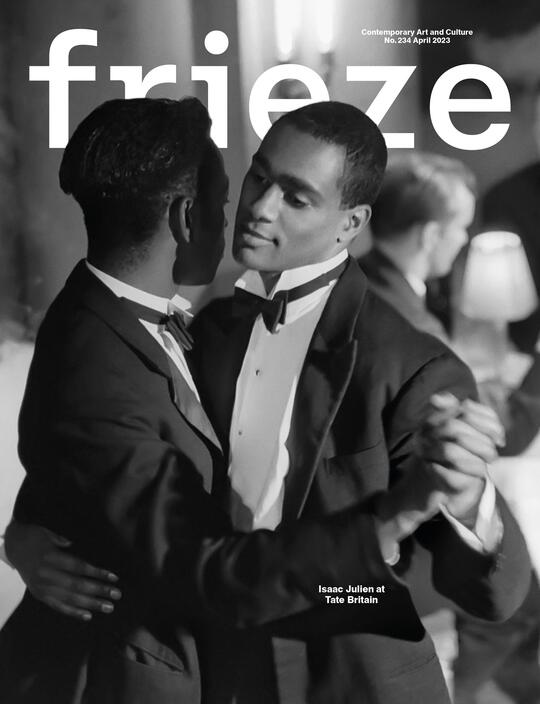

This article appeared in frieze issue 234 with the headline ‘Dossier: Four Artists to Watch in Gwangju’

Main image: Yuko Mohri, Circus in the Ground, 2014. Courtesy: the artist