The Radical Film Collective That Prefigured YouTube

The subject of retrospective at the London Short Film Festival, Videofreex’s Guerrilla TV tactics preceded the use of citizen-shot footage in contemporary media

The subject of retrospective at the London Short Film Festival, Videofreex’s Guerrilla TV tactics preceded the use of citizen-shot footage in contemporary media

Shown under the banner of ‘Radical TV’ as part of this year’s London Short Film Festival (LSFF), the works of the New York-based Videofreex – one of the first video collectives – make intriguing viewing at a time when the radical possibilities of television seem fewer than ever but those of the internet appear potentially limitless.

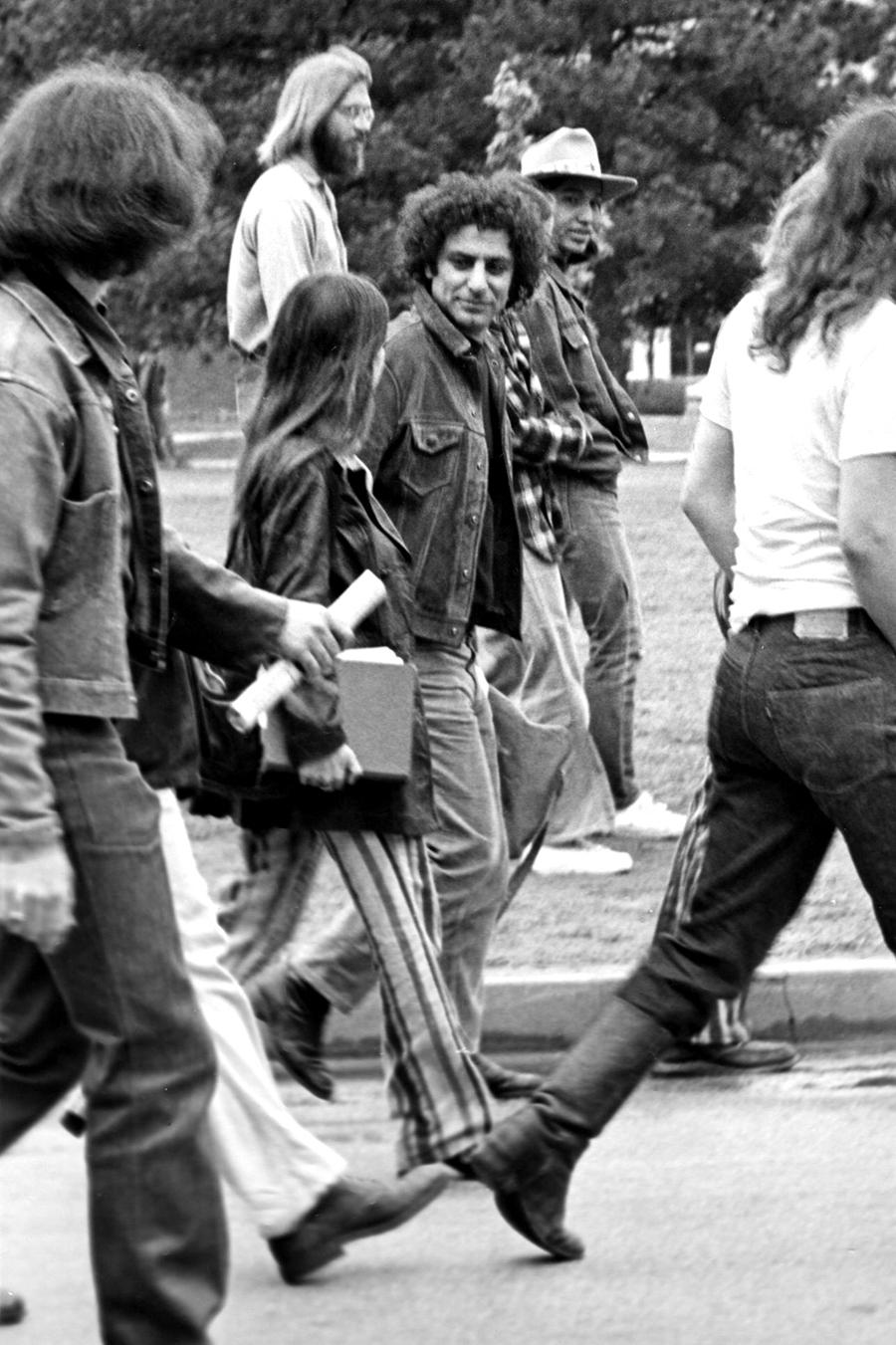

Videofreex was founded in 1969 by David Cort, Parry Teasdale and Mary Curtis Ratcliff after Cort and Teasdale met at the Woodstock Festival, cameras in hand, and they soon began to document the politicized American counter-culture of their time. Working out of a loft in Lower Manhattan, they used the Sony Portapak – the first consumer camcorder – in their plan to democratize television, dominated by the ‘big three’ networks. They briefly secured a slot on one of them, CBS, called The Now Show, for which they toured the USA, interviewing radical activists such as Abbie Hoffman of the Youth International Party (Yippies) and Fred Hampton of the Black Panthers. In 1971, they moved to Lanesville, New York, running one of the first media centres, documenting artists’ performances and providing behind-the-scenes coverage of civil rights and protest movements. The next year, they launched the first pirate station, Lanesville TV, and created innovative public-access television before they ran out of funds and disbanded in 1978.

The five films in the LSFF retrospective focus on Videofreex’s early documentation of women’s liberation, Black rights and anti-war demonstrations, and show how they both borrowed from mainstream news coverage conventions and sought to expand them. They asked people why they were marching, providing no voiceovers to direct viewers’ sympathies as they spoke to activists, antagonists and onlookers. This meant everyone got a fair hearing, but especially the radicals who could not hope to go on television without interruption and hostile questioning, with the length of their films – 20–30 minutes – offering more depth than most news coverage. This is especially notable in their long interview with Hampton, where he was able to discuss the treatment of Black activists from Martin Luther King Jr to Huey P. Newton, the Black Panthers’ take on Marxist–Leninist ideas, and his criticisms of the ‘counter-revolutionary’ Weathermen (later known as the Weather Underground) and their riots and bombing campaign against the US government.

The films also demonstrate the limits of their technology. Several end abruptly, with the sound slowing down and the image being overtaken by static as the videotape runs out. One protestor suggests they join the march, but the equipment isn’t yet portable enough. This, however, has the interesting side-effect of allowing them to show how dull protests often feel, beyond the most dramatic moments clipped for the news. Technology has evolved to the point where most people now carry high-quality digital cameras around in their phones and share short clips on social media and long-form broadcasts on YouTube or other platforms. Radical filmmakers can embed themselves more deeply in protest movements, or start wide-ranging channels with documentaries and talk shows, building on Videofreex’s pirate TV model.

Videofreex started by showing their works in their Manhattan loft on Friday nights, only expanding after a New York State Council on the Arts grant. At first, their audiences were locals, especially once they moved to Lanesville, or involved in the movements they filmed. Now, many of their works are available online, with an archive at the Video Data Bank and a few scattered across YouTube, Vimeo and, most interestingly, UbuWeb – whose founder, Kenneth Goldsmith, was one of the first to recognize the internet’s potential for democratizing access to the arts and media. Using UbuWeb’s Twitter account, Goldsmith exhorts users to download material, equally aware of how the possibilities afforded to platforms such as his – giving often copyrighted and sometimes contentious material to an audience who might not otherwise be able to access it – are dependent on the grace of service providers.

After two decades of internet centralization, these providers control not just the means of distribution but increasingly, with alternative media outlets using sites such as Patreon, the means of funding. These corporations are unlikely to ever stop citizen journalists from sharing brief clips of seismic events and having them go viral, but pulling the plug on radical organizations is far easier. Now, Videofreex’s project of keeping a record of the activist movements around them looks ahead of its time, and it has been continued, spiritually, by podcasters and online broadcasters such as Novara Media or Michael Brooks. Perhaps it’s even harder now for such collectives to secure distribution without interference, but given the oligarchs’ dominance over mainstream media and the pressure on digital platforms to clamp down on left or right insurgency, guerrilla TV tactics still need adapting – 50 years after Videofreex pioneered them.

Main image: Videofreex, Women’s Liberation Demonstration, 1970. Courtesy: Videofreex and London Short Film Festival