Frances Stark

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Non-Electrical Telephony and/or Lovers’ Telephone (2010) is the first work visitors encounter before entering Frances Stark’s Hammer Museum retrospective, ‘Uh-Oh’. Some may not notice it at all. Placed above the show’s title on the gallery’s exterior, the vinyl painting depicts the intricate plumage of a lone peacock on the side of one half of a tin can telephone in bold, black lines that share the same graphic quality as the didactic text below it. The imagery and title form a fitting prologue to an exhibition that centres on the mediation of self and the intimate, sometimes impossible, spaces of communication – aesthetic, linguistic or otherwise. Just as the drawn edges of the receiver in Non-Electrical Telephony ... have left the head and rear of her peacock out of sight, the figures and subjects of Stark’s works are often partial or contradictory, expressing narcissism or ostentation but also fragility, uncertainty and fragmentation.

Featuring over 120 works, this mid-career survey spans 1991 to 2015 and is arranged to highlight recurring themes, imagery and cultural references that are found in the artist’s deeply autobiographical practice. It’s difficult to approach Stark’s body of work without confronting the inherent conflicts that arise from negotiating identity through form. The artist is many things: writer, mother, teacher, lover. Her continually shifting relationship to these social and cultural roles are all on show here in tones and intensities that will likely leave viewers in a state of ambivalence.

While the works range from videos and sculptures to photographs, drawings, collages and mixed-media paintings, the artist seems less concerned with the material specificity of artistic media than in the direct transmission of information, usually through illustration or text. The majority of objects are 2D and are arranged on the wall in precise and orderly configurations. Stark’s writing also manifests as drawing, and her interest in letters and lines ultimately aligns her practice with the field of graphic design. This is evidenced in early pieces like Momentarily Lifted (2001), a carbon print that seems to emphasize typographical concerns: text as capable of conveying both linguistic and visual meaning. Or in her series of geometric chorus-girl collages, which features the artist hiding behind doorways, squatting or surrounded by a flurry of letters in intricately patterned dresses that produce dizzying optical effects. From band posters to carbon transfers to the printed matter Stark has cut up for her collages, the excess of ephemera has rendered the galleries strangely weightless in contrast to some of the heavier themes at stake. (For instance, how do race, class and privilege play out in the articulation of one’s identity?) Instead, she reminds us of the precious yet controlled space of the archive, of brittle strips of tape and handwritten marginalia, of epigraphic pages torn from their original sources. What happens to interiority when it is filtered through nostalgia and graphic design?

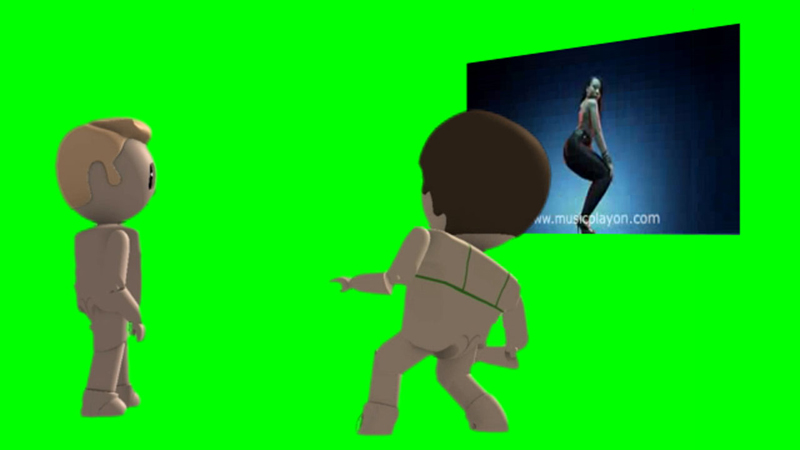

While some find pleasure in pallid forms and protracted viewing, Stark is well aware that the art public of our hyper-connected present moves at an accelerated pace. ‘No one can afford to pay attention,’ she says in her 2011 work, My Best Thing, a video that – alongside Nothing is Enough (2012) and Osservate, leggete con me (Observe, Read Along with Me, 2012) – manifests what the curators identify in wall text as Stark’s ‘literal promiscuity’. In all three works, Stark transforms the transcripts of her online sex chats into variations of video and multimedia installation. It is here that the artist’s tender prose and deft editing turns the potentially banal interactions of anonymous sexual encounters into compelling narratives that are both humorous and heartbreaking. Stark’s emotional vulnerability is endearing and these are her strongest works. In the serial love story, My Best Thing, the artist and her virtual partners are presented as plasticized animations whose emotive capacities have been reduced to the robotic gestures of Lego toys and the vocal inflection of TTS software. While these technological modes of representation seem ill-fitted for poetic musings on David Foster Wallace or the carnal moment of orgasm, it is precisely the limitations and inadequacies of these awkward avatars that elicit a profound kind of tenderness – one that mirrors our fears and failings with intimacy and love. Here, the artist struggles with the effable and ineffable experiences of subjectivity, the perpetual schism between the flatness of surfaces that enable linguistic communication (whether screen or page) and the more sensuous and palpable dimensions of desire and the body, which rarely find form in language. Ultimately, Stark shows us what it might mean to have one’s work bound to the negotiation and representation of self, as content, as image and as art.