Little Victories

The city that dozes but never closes

The city that dozes but never closes

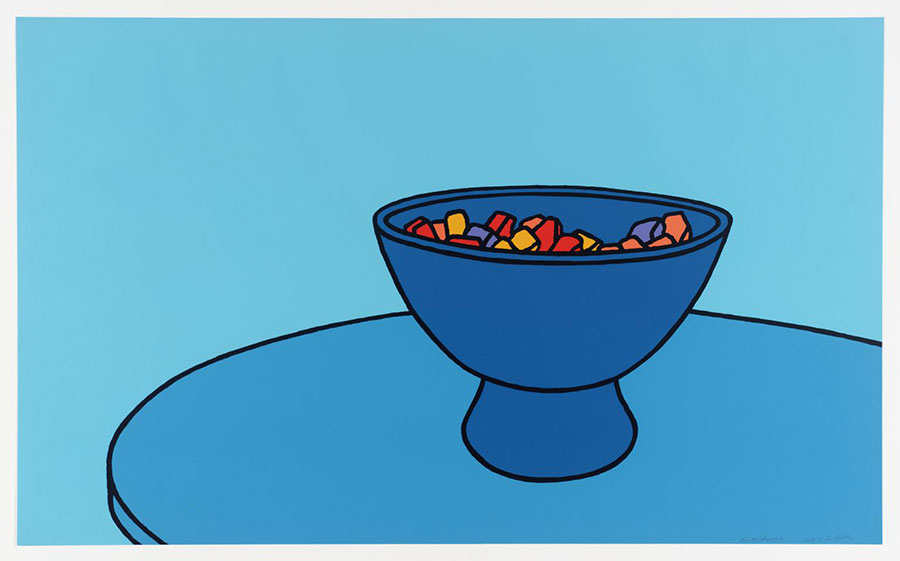

It's two o'clock on a Monday morning. Outside my window, the lights of Las Vegas stretch out into the cool desert night. The 'city that dozes but never closes' is dozing now, and there is not much traffic on the street. As usual, I'm sitting here in my little office writing a little essay on my little laptop, and, for the moment, I'm all right. To my left, sitting on my desk amid the stacks of papers and magazines, there is a small sculpture by Ken Price, the colour and form of which we could discuss at some length. A Patrick Caulfield silkscreen print called The Sweet Bowl hangs on the wall above the desk. It has been hanging there, over various desks in various cities, for 30 years. The only thing missing is my dog, Ralph the Beagle, who, were he still among the living, would be sleeping on my feet. If Ralph were here, things would not only be all right, they would be perfect, but perfect is not really the issue here. Small is the issue, and the virtues of a small life among serious books and difficult objects, writing small essays for a small audience out of personal conviction.

There was a time when things would remain all right well into the day, when I could make some fresh coffee, walk out onto the balcony and watch the dawn reflected on the western mountains. No more. When the sun comes up, the phone will ring, the fax will ping and the e-mail will start blinking. All smallness and intimacy will evanesce. The flutter of the breeze around my face and shoulders, the subtle glimmer of Kenny's sculpture and the cool asymmetry of Patrick's print will recede from consciousness, and I will be thrust once again into the far-flung enormity and litigious impersonality of what now passes for contemporary culture. E-mails will solicit my opinion on the apocalypse of the moment, on the relevance and educational efficacy of contemporary art and its institutions. I will fill out three-page information sheets for bureaucratic support workers at institutions where I have been engaged to lecture. Only a few years ago pundits did punditry and lecture engagements were handled with a phone call and a little chat. Now I am solicited for sound bites and booked like a caterer, with instructions to be standing at a certain place at a certain time, from where I will be escorted to the podium, whence I may find my own way back to the airport.

The amazing thing about all of this is that I haven't changed at all, nor has my practice. I write as much as I always have and for the same venues. I make almost as much money as I did in 1972, and exercise no more worldly leverage than I did then. The art world has changed around me, however, and not, in my view, for the better. For 25 years I was a journeyman artisan in a marginal industry whose size was commensurate with its public importance. Today, I am a plug-in sub-contractor in a bloated corporate culture that has embraced all the wickedness of mass culture and mass education in its quest for dollars at the door. More distressing still, I find myself inadvertently complicit in this lemming-like rush toward the mainstream. In recent years, I have published two little books--a polemical broadside about beauty and a collection of narratives about popular culture. These books were intended to be what they are in fact: footnotes appended to the hundreds of thousands of words I have written about difficult art for appropriately specialized publications. These footnotes are now considered to constitute my entire oeuvre, to define my thinking about art. The knowledge I derive from this ludicrous anomaly is that denizens of the new, mainstream, corporate art world are more interested in a raconteur chatting about Liberace than in a serious critic writing as clearly as he can about an artist as beguiling and difficult as Robert Gober.

Traditionally, of course, the difficulty of serious art such as Gober's has mandated the smallness of the art world, on the presumption that an art community is composed of people who wish to engage and come to terms with difficult art. Waiving this prerequisite has made the large art world possible. Unfortunately, without the mandate to engage difficulty and opacity in works of art, difficulty and opacity themselves have become schtick--visual attributes that distinguish the spectacle at the kunsthalle from the spectacle at the cineplex. We know it's art because we don't understand it and don't plan to try. Comfortable disinterest in the presence of things that elude one's understanding, however, constitutes the very definition of philistinism, and, today, of course, philistinism passes under the guise of tolerance. We refuse to engage difficult objects lest we find them wanting, trivial or inconsequential. This, of course, would signify our intolerance--and this, of course, would limit our target audiences, cost us dollars at the door, and necessitate a smaller art world--which raises these questions: could any culture ever produce enough interesting art to fill the spaces presently available to exhibit it? Would it matter if it did?

After my experience of the last two years, I think not. During this time, I curated a modest international exhibition for an institution in New Mexico, and I hasten to assure you that selecting and designing the exhibition were a genuine pleasure. I was allowed to indulge my passion for tiny increments, eloquent gestures and fine distinctions; I was allowed to work with artists who care about such things, and we were allowed to get it as right as we could. The experience of being allowed, however, soon became chastening and strangely demeaning. At the outset, I assumed that I was being recruited because of what I believed. It turned out that I was hired because I believed something--and that, whatever I might believe, the institution was there to make it so, and it did. The fact that I wanted to make a large exhibition look smaller, to make large spaces seem more intimate, to change door heights, door widths and wall lengths by inches rather than feet, mystified those assigned to assist me, but assist they did, because they were there to help.

The entire project left me deeply unrequited, however, and this dis-ease may be taken as a signifier of my own obsolescence. I have always conceived of cultural institutions as representing constituencies of artistic conviction that have their life spans, and then, as styles and fashions change, fade from prominence. More to the point, I have always taken the overthrowing and reforming of cultural institutions to be the artist's and the critic's first secular task. Contemporary artistic institutions, however, by assiduously abjuring any artistic conviction, have rendered themselves virtually invulnerable to overthrow or reform. Artists and critics, it would seem, are supposed to have convictions; institutions, cast in the role of parental overseers, are presumed to be above all that. Thus, the exhibition that I conceived as a tiny but heartfelt mandate for change was conceived by its sponsoring institution as an exercise in privileging sufficient diversity to ensure its perpetuation.

This new structural order in the art world has three important consequences. First, the efforts one expends on behalf of one's artistic convictions can have no possible consequence at the administrative level of international culture. Art may change the world, incite revolution, but it will almost certainly leave its administrative institutions intact. Second, the whole idea of having artistic convictions is effectively infantilized by the parental oversight of disinterested enablers who, having no artistic convictions themselves, cannot help but regard those who do as wilful children. Finally, the present situation guarantees that there will be no social commonality or continuity of interest between those who administrate official culture in its stratospheric, abstract sweep and their clients--the artists and critics who live in the world of light and air, thought and feeling, love and language, colour and objects. These earthly creatures who make small distinctions that they have every right to hope will have large consequences are trivialized even as they are lionized.

Strangely enough, it is the simple disjunction of interest and enthusiasm between those who administrate artistic culture and those who execute it that I find the most distressing on a day-to-day basis. I was wondering the other day: what if the pleasant young woman from the institution who calls to secure my address and social security number were to ask me what I thought about Robert Gober's piece in Venice? What if the pleasant young man in the expensive suit who escorts me from the door of the museum to the podium were to express some interest in the topic of my lecture? I honestly don't know what I would do. I would probably break down in tears and tell them everything. I would tell them about my nifty Ken Price and the breeze off the desert, about the essay I just wrote about Roy Lichtenstein's brushstroke paintings and the ebullience of my late dog Ralph, about the book I just read and the painting I just saw. Fortunately, for my public dignity, this will never happen, but it should.