Born to Lose

Getting down with the Melvins

Getting down with the Melvins

In the 1970s, the word 'concept' had very different connotations in Rock music than in the visual arts. Conceptual art emitted an aura of purity, intellectualism, and the purging of illusions. But in the heroic, and now largely forgotten, era of 'Progressive' Rock, the 'concept album' was usually a bombastic attempt to develop larger formats for the expanding genre. Soon the term was used only in mockery; it seemed to embody everything that Punk rebelled against.

For over 15 years, the Melvins have been working on both versions of the 'concept'. The band's original members, guitarist King Buzzo and drummer Dale Crover, are as interested in the great, tragic failure of the more expansive forms of Heavy Metal and Progressive Rock as they are in extraordinarily strict experiments: both serious and parodic approaches to Conceptualism as it is understood in the visual arts. The Melvins, working in the American Northwest, were originally associated with post-Punk, although they were initially lumped together with Grunge. (Kurt Cobain was an early fan and friend of the band.) On Crybaby (2000), the last album in their trilogy about sissies and wimps - the first two were The Maggot (1998) and The Bootlicker (1999) - they pay tribute to that big crybaby Cobain, and the seriousness and dignity of his wimpiness. The record's opening track is 'Smells Like Teen Spirit' with Leif Garret on lead vocals. Garret, one-man boy group of the 1970s, naturally embodies 'teen spirit', even though he's pushing 40. Nirvana's song, which expresses an ambivalent attitude to the term 'teen', is confronted with exactly the thing it tries to dismiss, creating an ambivalent archaeology of the Grunge phenomenon.

This archaeology is part of a commentary on a wide range of issues involving the development of Rock music in the 1990s. Next to a track with a serious attempt at Progressive Noise Improvisation, or containing a collaboration with someone such as Mike Patton or Jim Foetus, you might find a very traditional cover version of the Hank Williams' classic 'Ramblin' Man', sung by his grandson Hank Williams III. But the Nirvana track makes the most decisive point: played note for note, as if looking at the song under a magnifying glass, it is clear that the Melvins love details, the microscopic view of the joints and hinges of a composition. Every famous break, each dramatic power chord, is slightly more emphasised, set free, laid open. This is their speciality, the core of their theory of Rock music. The heavy forms of Rock are not about the melodies, songs, lyrics, intensity, drama, and cadences, but very special 'places' - specific breaks, intros, and upbeats.

The Melvins have preoccupied themselves with taking small, seemingly functional parts out of Rock song constructions and repeating, bending, and tearing at them for minutes at a time. It came to the forefront on the 1992 album Lysol (which had to be renamed Untitled when the manufacturers of the deodorant objected). Some listeners misinterpret this process as slowness, but it has more to do with the idea of parallel ideas in Techno and House music; that is, the attention that is paid to the smallest units of Pop music, to the rapt immanence of the space 'between' the bits of music. In the case of House and Techno, this view through the musical magnifying glass found its way onto the dance floor, but in the case of the Melvins, it persisted in being the pleasure of a fetish-obsessed fan for his subject.

The most radical celebration of classic 'parts' of Heavy Metal culture taken out of their context can be found on a three-CD series from 1992. Each disc is named after one of the band members at the time. Starting with the cover design, the entire project sidled up in a half-parodic, half-admiring way to one of the swankiest large formats of Rock history: the four-LP series made by Kiss in the 1970s. With his 23-minute 'Hands First Flower' on Joe Preston, bassist Joe Preston, who unfortunately left the band, took the principles of the Melvins to the peak of an ambivalent art. Bizarre structures leave behind the insoluble question of whether they are denouncing an exaggerated pleasure in monotony - in the breaks, the intros, and all the banal bits - or whether these structures show how certain jokes and a strong musical structure can take any sort of exaggeration, even when the original song has long become boring.

The vocabulary of conceptual interventions in the structural rules of Rock music and its emotional functionalism has been strongly refined since then. Prick (1995) consists of nothing but little units. It lays bare not only song construction, but the materials used to create the sounds, employing the characteristic noises heard at live concerts, acoustic side effects of radio-microphones, unamplified Blues songs and, once again, long drum solos. Also on Prick is a long-overdue acknowledgement of a milestone of Modern music. In 1969, Yoko Ono and John Lennon reacted to John Cage's 4´ 33› by recording a Pop rendition of 'Two Minutes Silence'. The Melvins answered with the impressive 'Pure Digital Silence'.

The Melvins' intelligence always shows itself in the way they address and formulate larger contexts. They are always looking for ways to explore the great aesthetic problems via Metal and Punk: part versus whole, functionalism versus autonomy. For the Melvins, it is not just about punch lines. Their love of the abstract exploration of details addresses the aesthetic sensibility of the 'regressive listener'. Adorno morosely called these people 'part listeners'; as early as the 19th century, there were those who wanted to hear the same cadence over and over again - people who 'could not listen enough'. 1

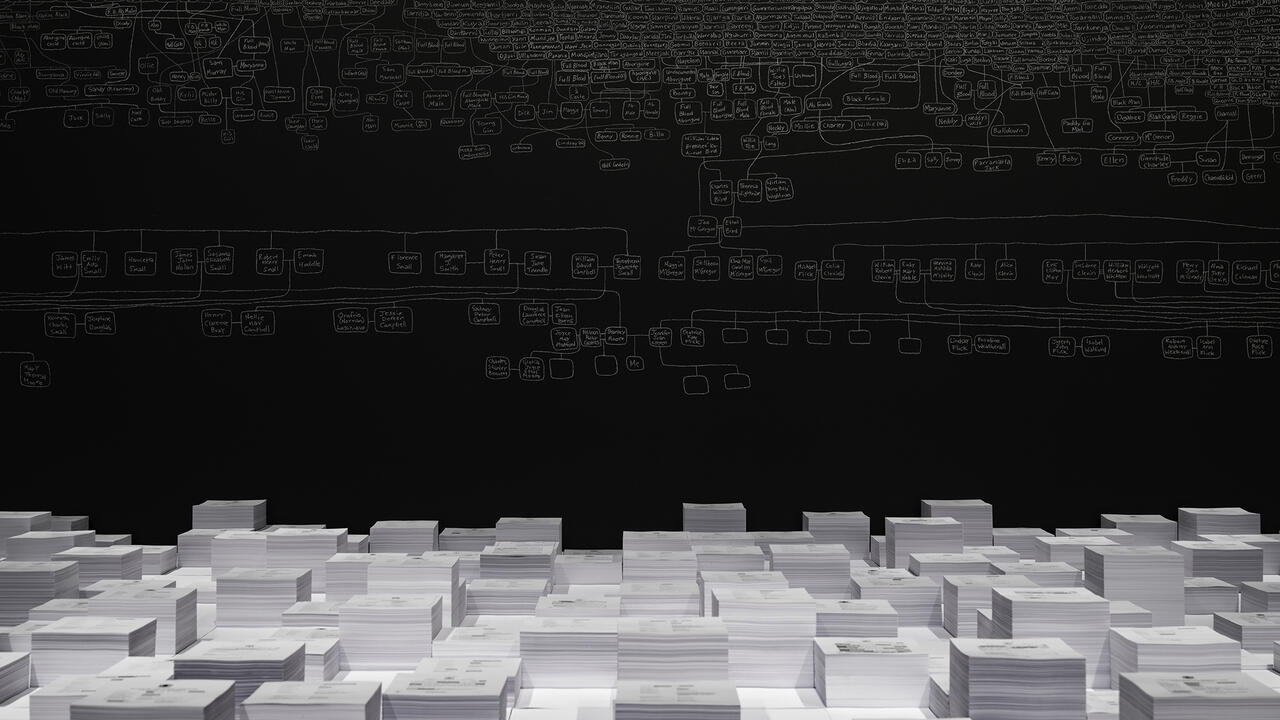

That the Melvins' fetishistic regressions are over the top is not a criticism of this type of listener. Instead, it highlights some of the most important things about current Rock that cannot be found in either the song format it shares with Pop, or in the economy found in Jazz and some Classical music. When the Melvins define the 'nuts and bolts' of a track as its most crucial element, it goes beyond reduction - in the sense of the Minimalist display of materiality in art - and suggests a basic theory of Rock music. For the Melvins, this research into intros and transitions has become part of a blueprint for a larger format. On Honky (1997), the grandiose form of the concept album lead to a substantial preoccupation with the details of the sonic aesthetics of Progressive Rock and its reappearance in declining forms, such as Angelo Badalamenti's music for David Lynch. On Lysol, the Melvins defined the entire album as one track on the CD's digital layout, although two recognisable cover versions of songs by Flipper and Alice Cooper are hidden on the album. And on almost all of their albums from the 1990s there is a closing piece of 20 to 30 minutes (sometimes as a hidden track), which, like an anthology, juxtaposes Dadaistic and extremely conventional ideas.

This preference for the odd, for the extremity of the conventional, is in accord with the Melvins' excitement about the backwoods of America, although their enthusiasm is free of the romanticism and fashionable sensationalism of many current adaptations of White Trash 'style'. The Melvins recently met up with Cameron Jamie, who invited them to record the soundtrack for his black and white Super-8 silent film BB (2000). Jamie has long explored various wrestling subcultures, as both wrestler, documenter, and artist. His latest film was shot at one of the many backyard wrestling tournaments that take place in the American suburbs. Just as the Melvins isolate the theatrical gestures of Kiss and then take them beyond the pain barrier, these adolescent boys take the appearances of their wrestling heroes rather too earnestly, to the point of real violence.

On a US tour this autumn, the Melvins will accompany the film. And perhaps this will be the manifestation of their longed-for Gesamtkunstwerk of celebratory failure.