The Egg Trick

Eva Löfdahl

Eva Löfdahl

Like most children, I was once tempted to become a magician. The temptation came in the form of a rather crude 'How-to' booklet, in which the only really compelling trick was how to get a whole egg into a bottle without breaking it. I never tried it out, though; I did not believe in it. I did not believe because the implications of believing were dangerous. If it did work, I would be subject to a magic far greater and darker than the banal card-and-coin tricks the booklet could teach me. I would no longer be the 'magician' - the trick would be on me. The egg trick was in fact a small matter of kitchen chemistry, but before a certain age, chemistry - the inexplicable workings of matter - is all magic. Disconnection of known connections. Connections where there should have been none. Safer, then, not to believe.

According to the booklet, this is how you get a whole egg into a bottle: you soak the egg in vinegar until the shell is soft like rubber, then roll it to become a narrow sausage, slip it down the bottleneck and add water. After a while, when it has regained its original shape, you discard the water. I was reminded of this profound transformation when I first saw an object by the Swedish artist Eva Löfdahl in which a white stone ball, approximately the size of an egg, is contained within a bottle. Except that the bottle has been broken, then glued back together around the ball. The ball, which is connected to an identical ball by means of an aluminium pole through the bottleneck, seems to support the bottle rather than being contained by it.

It is a representation of failed magic - a trick that did not work. And yet the work alludes to several orders of magic. At first it evokes a magic which is in fact highly rational, an example of the ultimate order of the world, despite everything. Eggs will metamorphose into sausages, then pop right back to their original shape. Once beyond the bottleneck, narrow ships will grow enormous sails by means of strings. Watch the stars and they will tell our futures. Löfdahl breaks the bottle, as if to demonstrate the construction of magic, the rationality of cheap tricks. And yet the roughly glued pieces of glass evoke not just common sense - and the comedy of common sense versus high-minded strategies - but also a different sort of magic. They evoke a magic of disconnection, of words and operations that fail. They even evoke a strange form of belief - forced, the way the bits of glass are forced together with glue. Against her cold disbelief, a darker and more basic magic leans.

Now imagine Theodor Adorno under the Californian sun, writing in his habitually irritated tone about the horoscopes in post-war LA newspapers. 'The tendency to occultism is a symptom of the regression in consciousness', he declares, true to form. 1 Consciousness has regressed, he claims, because it not longer has the power to imagine the otherworldly while at the same time enduring the actual world we live in. Instead of taking time to work it out, to define these two dimensions in their unity and difference, we now mix them indiscriminately. In the modern capitalist version of astrology, the otherworldly seems accessible to us as 'fact', while the actual world becomes an immediate and obvious given.

Occultism, of course, is 'bad'. But what seems to insult Adorno is not a widespread belief in magic, but rather what he perceives to be a lack of spiritualism: a standardising and pre-packaging of the world into a complete set of 'connections' that may be 'read' by anyone carrying the requisite expertise. What infuriates him is not mad hocus-pocus, but the dry, common-sensical tone of the weekly astrology columns, the basic rationality of the assumption that existence moves according to a predictable plan in which everything finds its place and chance does not exist. Here, the stars are, as he puts it, 'down to earth'. Down to earth or down home: 'The platitudinously natural content of the supernatural message betrays its untruth. This is what makes the prosaic so cosy', he fumes.

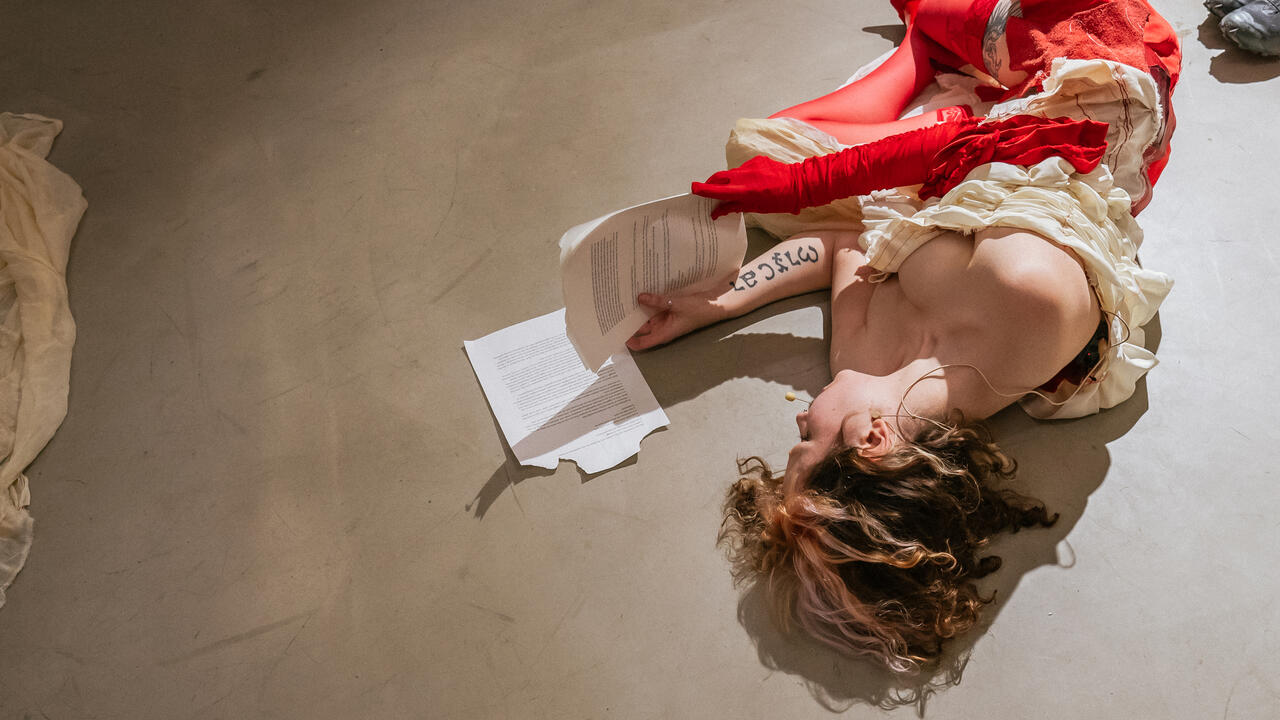

It seems that it would take a certain measure of disbelief to restore any sense of the spiritual, any sense of the relationship between the 'world' and the 'otherworldly'. It would appear that a link could only be established through a sense of disconnections and failures, an acute idea of where a particular dimension no longer applies. A link that does not link up is inconceivable, and perhaps that is precisely the point - perhaps it can only be represented by the most concrete and uncomplicated image. Löfdahl, for one, seems to shun complications. In her most recent work (at the 1995 Venice Biennale, for instance) she goes about the question in an almost bluntly matter-of-fact way: with ropes. Tying the knot, measuring out the distance. Forcing the link that is or isn't there. Indeed, in one of her first public performances several years ago, she held on to a rope, holding it up close to a screen on which slides were projected. The rope, extending from the middle of the screen to the middle of the audience, traced a fictional and yet entirely concrete connection between spectator and image, a connection whose fictionality was both underscored and erased by the changing of the slides...

Still, to leap in at the deep end and describe this as spiritual? I would have hesitated, had not Löfdahl provided several clues leading in this direction, luring me to see her work as realising exactly the kind of thought Adorno was demanding, if only through a series of stringently formal operations. She names many of her works 'models', but they are not models for anything except themselves. They indicate 'systems' that are supposed to 'work' but don't. They stand alone, giving off a sense of disconnection. She talks of such disconnections, failures or inabilities as suggestive of a particular dynamic that she is trying hard to get at, trying hard to describe. If the work somehow fails or comes to a halt, will it then indicate the end of one dimension? Will it somehow indicate the limit that separates one dimension from another? The memory of Duchamp and the whole bunch of artists who played with the possibility of movement across to the fourth dimension comes to mind. What credulity! Löfdahl moves with doubt and hesitation. She puts it this way: 'In the notion of an immaterial reality there is also the notion that something separates us from it ... By necessity the work of art establishes a separation.'

'Down to earth', 'down home'. 'This is what makes the prosaic so cosy.' One can almost hear Adorno's scorn, but at least his fury induces a defence. For not all notions of home are cosy; home does not always equal reality. When I first saw Löfdahl's recent work, it was 'home' that came to mind. Not my home, just home: it seemed to have more to do with an elusive quality of inhabiting in general, an essence of the experience of a well-known place. The word 'home' appeared, like a flash of lightening, at the sight of two formidably prosaic yet completely strange objects resting on the floor: two matt white lumpy balls made of plaster and epoxy resin that had metal screws driven into them from above. The prosaic was located in the building materials, plaster and screws, and in the sense of domestic handiwork: nail to board, clasp to window, handle to door. These are the details that suggest the construction of 'home' - the myriad nails, screws cables, clasps and knobs which we manipulate with such skill, only to let them become invisible to our general purpose.

Still, the everyday objects were counterbalanced by a strangeness: the strangeness of building materials taking control. It was the kind of strangeness that comes from a momentary lack of concentration, like in a daydream. Mesmerised, daydreaming, losing concentration, one can experience the details that construct the 'home' coming to life. One might notice how the metal of the keyhole tears into the dark wood of the door, how the clasps disturb the even white lines of the windowpanes. A sudden aspect of defamiliaristion sets in. This is where the prosaic sheds its 'cosy' skin. Reality is no longer an obvious given, unreality no longer connects everything in one big web of meaning. For the unreality evoked by the lumps and the screws only appears unreal at the moment one introduces constraints. Löfdahl sets constraints, tries, again and again, to find out where the limits are. Her aim is not to express the immaterial or the unreal, but something both more modest and more precise: simply to indicate where such immaterials might be located.

In his book, The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard put it this way: 'All we communicate to others is an orientation towards what is secret, without ever being able to tell the secret objectively'. 2 The secret - or the dimension that we do not know - is always linked to a sense of place. 'I cannot tell you' you might say, 'but it was right there, in my dream.' And so Bachelard goes on to insist on the notion of 'home' as the point of departure for the formation of such secrets. For home is the place which forms the ground of the daydream - the instant's freezing, as he calls it, asserting in the same breath the daydream as the basis for the poetic image. And the poetic image negotiates the balance between reality and unreality.

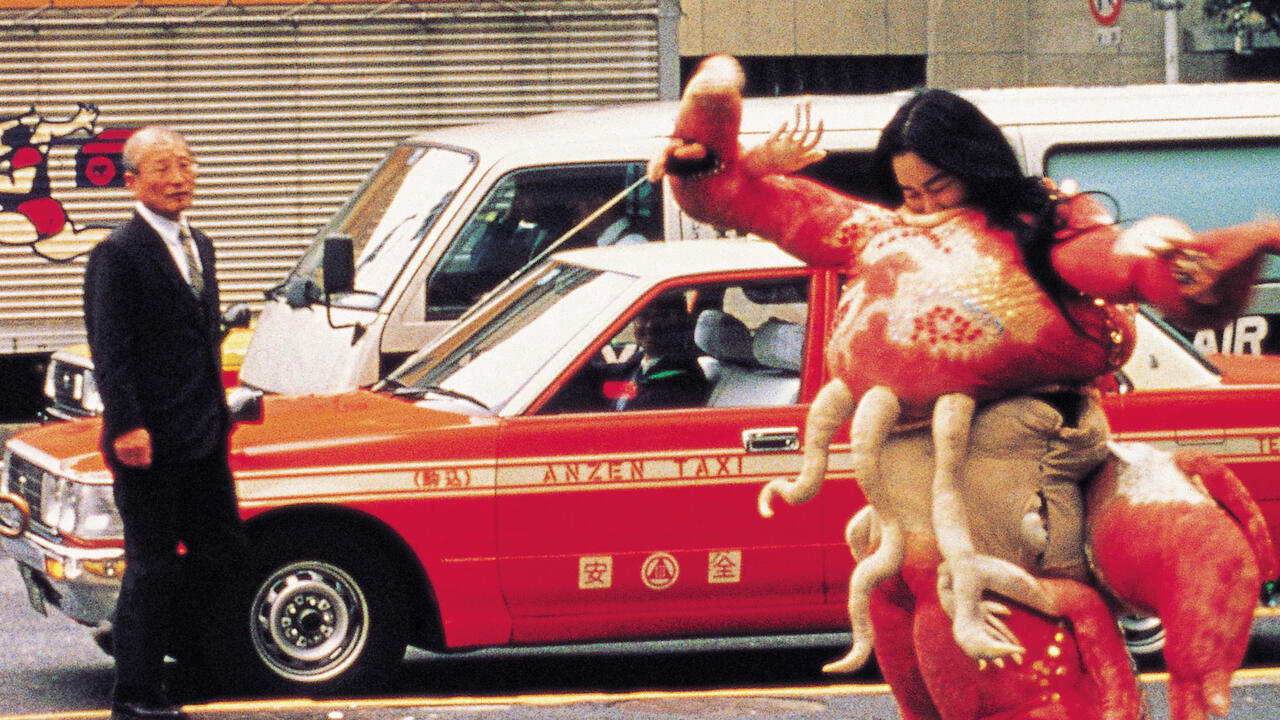

So here's a double image of a home: a home that exists both in reality and virtuality. To define such a place, Löfdahl created a series of inverted spaces, '...leaving the visible spectrum', as she put it. Some she placed in a gallery, others she placed, and photographed, 'in anybody's home'. Their counterpart seemed to be the particular presence of the minimalist cube. For rather than placing an entity in a room, Löfdahl somehow drew lines in space, as if with a soft and particularly grainy piece of charcoal. In this series of constructions, where thin rods of flock-coated steel trace the outline of cubes - each cube encasing a void or non-space, which is also a part of real space. The void appears as soon as the room fills with people or furniture because the cubes set up a limit. No matter that the limit is a precarious one, as the furry blur of the flock-coating and the rather wobbly construction indicates: curiously, it demands respect. And maybe we respect it because, against our better knowledge, it seems to contain a mystery. Nothing seems to exists inside: leaving the visible spectrum, there is nothing to see. And nothing, of course, does not exist.

In another body of work she seems to invert this experience, as if she feared the cubes might finally freeze in a too clear-cut division between real and unreal. Instead of drawing in space, this work takes place in the two-dimensional field where lines usually belong, where we all accept their workings as purely virtual. On a piece of paper, Löfdahl plays with the optical 'is it or isn't it' effect of projection and retraction of geometric figures. It is the psychological game of hiding two images within one: making 'spaces', so to speak. But soon enough she breaks out of the facile little paradoxes of this game with a series of sudden gestures. Scattered here and there on the paper are some strangely banal depictions of 'corners', but within the relative virtuality of the lines-on-page context, they seem as quick, as actual, as real events. They indicate the suddenness, the unforseeableness of the whereabouts of limits and locations.

Once you start inhabiting her space, then, limits and negotiations of limits begin to appear everywhere. In fact they proliferate, even reaching the field of beauty and decoration. In a series of graphic works she depicts four versions of feminine plaited hairstyles seen from the back. The hairstyles are just that - styles. Floating in a black void they are as abstract and bodiless as demonstration hairpieces in a department store. You can, and may, appreciate this beauty innocently: the intricacy, even cunning of the plaits mirrors the exacting work of the pen that reproduces them, hair by hair. Once upon a time, when women still had plaits to cut off, the bodiless plait was the fetish object par excellence. The little drama of the fetish somehow strikes to the core of Löfdahl's negotiations of the limit between dimensions. According to Freud, the fetish works as the ersatz object for the experience of the mother's lack of penis, an object that is supposed to allay a fear of castration. But of course the fetish keeps the horror alive as it consoles: it is a concrete physical object that always signifies a deficiency or disconnection. It stumbles around a void while speaking very loudly and very self-assuredly of fullness... The lovely and exacting work of the pen, like the work of art, establishes a separation.

She uses words carefully, circumspectly: some things are hard to think and even harder to say. But she launches a parable, itself a formula of sorts. 'You leave where you enter - or don't you?', she says, adding the following image of movement in a space that is subjected to more than one concept of its limit: 'In through the fire escape and out through the reserve exit - a posture, head on and a little to the left like a ghost train.' I keep thinking that she may still be looking for this place 'a little to the left'. But only because she didn't believe for a moment that it could actually be reached.

1. Theodor Adorno, ed. Stephen Crook, The Stars Down to Earth and Other Essays on the Irrational in Culture, Routledge, 1994

2. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas, Beacon Press, 1969