Franz Erhard Walther

This was the first solo outing in the UK for a 72-year-old artist whose place in history might have been ensured by his participation in Harald Szeemann’s legendary showcases ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ (1969–70) and documenta 5 (1972), but whose reputation outside his native Germany has been greatly enhanced by recent retrospectives at Mamco in Geneva (2010) and Dia:Beacon (2010–12). The earliest works included, from 1958, register the precocious and prescient talents of an artist then still in his teens. While the selection of these ‘Schraffurzeichnungen’ (Hatched Drawings) show Franz Erhard Walther working briskly through the still-fresh legacy of Art Informel, it’s difficult today to address his ‘Wortbilder’ (Word-Pictures) from the same year without thinking of what Ed Ruscha would cook up a couple of years later, several art worlds away.

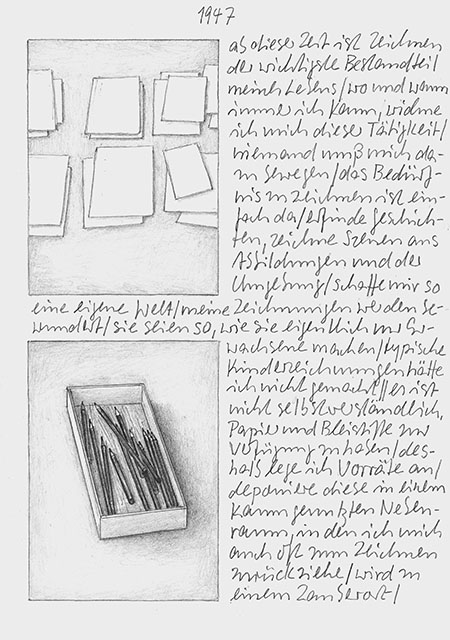

This cannily staged quandary was emblematic of an exhibition buoyed by the privileges of hindsight, as these early works were bookended by the presentation, in the last gallery of The Drawing Room’s new space in Bermondsey, of 71 of the 524 works on paper that constitute ‘Sternenstaub’ (Dust of Stars, 2007–09). Described as a ‘Drawn Novel’, and combining drawing with handwritten narrative, this fascinating apologia pro vita sua – executed in pencil on A4 sheets and tellingly subtitled ‘71 Selected Memories’ – provides an informative and highly entertaining account of Walther’s thinking and making up to the year 1973. His international visibility waned somewhat after the 1970s, like that of other pioneering artists of his generation and inclinations, though he continued to produce significant works and was an influential teacher for many years at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg.

Renewed interest in Walther has inevitably focused on the 1960s, specifically on the ‘1. Werksatz’ (First Work Set, 1963–9), a series of sewn-fabric sculptures designed for loosely structured, interactive use by pairs or groups of viewers. Several other fabric works were also shown, most notably Drei breite Bränder (Three Broad Bands, 1963), an arrangement of canvas strips nailed to the wall and snaking down to an unruly heap on the floor, providing a notional bridge between the acknowledged precedents of Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni and the American post-minimalism Walther anticipates in certain respects. Equally intriguing just now, in the wake of Relational Aesthetics, and given the resurgence of performance and dance in the visual arts, is the challenge of triangulating the fabric sculptures with a range of roughly contemporaneous interactive works by artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark, as well as, for instance, Franz West’s later ‘Adaptives’. (Walther dates his discovery of ‘the hand as pedestal’ to 1962–3.)

The Drawing Room is an apt venue for an artist for whom paper has always been more ‘source’ and ‘site’ than mere surface. As we learn from ‘Sternenstaub’, by his late teens Walther was exhibiting locally and experimenting across media. (A ‘graphic-sculptural action’ from 1958 is recounted and illustrated, in which he performs as a human ‘water-spout’ – Bruce Nauman scholars please note.) A classmate of Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke in the Düsseldorf Academy, his relationship with the mage, Joseph Beuys, was not without its awkwardnesses. (Beuys’s sly remark to some of his more reverent disciples – ‘So Walther has become a tailor now’ – clearly niggled, and is cited twice.) He moved to New York in 1967, stayed for the next six years, met everyone, and was included in the epochal exhibition ‘Spaces’ at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1970. Various luminaries drift through the gapped narrative, including Eva Hesse, Fred Sandback, Walter de Maria, Richard Serra and Richard Tuttle. Marcel Duchamp calls and is keen to meet him, but dies shortly afterwards – a missed encounter and an abiding regret.

What most distinguishes this idiosyncratic memoir from others of its ilk, however, are the persistently thoughtful distinctions Walther draws between his specific concerns and those of his fellow artists. He is intrigued by Claes Oldenburg’s engagement with sewn fabric, for example, but notes that he himself ‘is aiming for something quite different …/ while in a stored state the work pieces are forms / in action they become instruments and the actions become forms and thus works’. Such valuable musings merely added to the surfeit of riches displayed in a packed, but finely modulated show.