The Invisible Dragon, Dave Hickey

Art Issues Press, Los Angeles

Art Issues Press, Los Angeles

With the approaching millennium, it may be inevitable that the word ‘beauty’ creeps back into aesthetics. Much of the elegance and blather of The Invisible Dragon can be explained by this fact alone. His ‘Victorian mentor’ is Ruskin, Hickey claims in the preface. Wrong. For better or worse, his mentor is Walter Pater, even Wilde who, taught by both Ruskin and Pater, planned his own finale like the anarchist in Conrad’s Secret Agent who turns himself into a human time bomb.

One main feature links Hickey to these great figures: he writes like a dream. But sometimes being so articulate hinders more than it helps. Beauty as an ‘issue’ popped into his head at a symposium, Hickey confesses at the outset. The result was presumably this book, on the theme of the fate of the experience of beauty. One reaction would have been to pretend it never happened, to have deviated into controlling or administering it. But muffling an d mitigation are the self-appointed jobs of the museum curators, he argues, modelling themselves on Alfred Barr in his time at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Barr becomes the villain of the book. Its hero, on the other hand, is Robert Mapplethorpe, whose work has recently inflamed the museum officials, diplomats and other human apparatus of large museums. This polarity and its obviousness is the peg on which the rest of the book hangs. Yet partiality mars what could be a clearer thesis. Seeing Mapplethorpe referred to as ‘Robert’ all through the book, the reader realises the danger of the elisions the author makes so suavely.

In itself, art is amoral, and that very amorality leaves it open to abuse. Mapplethorpe was a collector, an aesthete. In his work, careful choice led to perfection. But despite this precise approach, the meaning of the work remains open. Thus it is easy to pin arbitrary explanations on it. (No European viewer would look at pictures of naked black men posed like specimens on tripods and imagine them to be a vote of support for the Black cause in general, for example, a surprisingly common argument in New York and, as Hickey acknowledges is never ‘plain,’ nor ‘appearances’ sincere. But who bestows meaning on images, after all? The Viewer? The Buyer? The Artist? Representatives of Church or State did so for a while, Hickey argues, but as their power declined, images became ‘mobile’ and ‘irrevocably political’ and the private encounter between the image and its beholder took on the task of changing the public character of institutions. Pictures have work to do in the world. For example, making sex beautiful was Mapplethorpe’s triumph, as Hickey sees it. And that has no place in museums, which he calls ‘therapeutic institutions.’

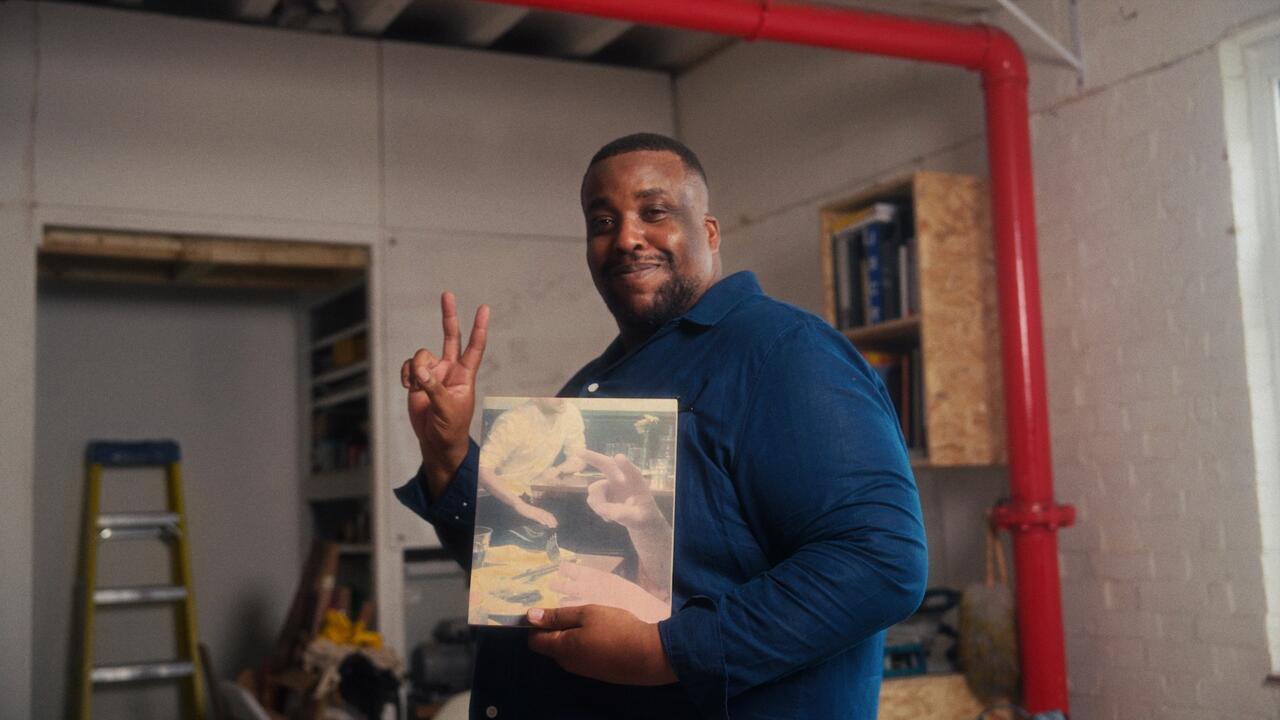

At the heart of The Invisible Dragon is Helmut and Brooks, New York City(1978), In other words Mapplethorpe’s notorious fist-fucking picture. Hickey points out that such images ‘collapse and conflate our hierarchies of response to sex, art and religion – and, in the process, generate considerable anxiety.’ The artist positions his or her art at an intersection between all possible contexts (And traditionally, gets off scot-free, the single fact the establishment cannot abide.) Triumphs in the past, like the conflation of spiritual and carnal in Renaissance art, have made this possible. Today the enemy of such an approach is the museum: Hickey argues that the growth of museums as arbiters, of The Gospel According to Barr, followed a period of particularly unbridled imagery. The museums’ final solution to this activity and – Barr is repeatedly compared to Goebbels in Hickey’s book – is to pretend that art in institutions is an end in itself and not an instrument.

Perhaps it is difficult for us to avoid nodding assent to this hijacking of the real purpose of art. It would mean denying museum staff jobs, dismantling meaningless prizes for artists and closing down museum-controlled magazines that provide anodyne ‘coverage’ of the institution’s exhibitions. But we should then remember that all this nonsense that we are forced to endure is funded by pubic money. Nagging, elegant, and violently partisan though it is, in the final analysis Hickey’s book is probably too polite by half.