Michael Nelson Jagamara & Imants Tillers

‘The Loaded Ground’ was a retrospective covering the collaborations between Michael Nelson Jagamara – an Indigenous Australian artist associated with the Papunya School painting movement that emerged in the Western Desert in the early 1970s – and Imants Tillers, an Australian artist of Latvian descent and a key figure of appropriation art of the 1980s and ’90s. A mere glance at these biographical details reveals an ideological rift that would appear to be difficult to reconcile on the surface of a canvas: Jagamara’s paintings are often custodial records of his Dreamings, comprising pictorial signs from Tjuringa and rock art designs that denote and preserve Ancestral Warlpiri stories; Tillers’ paintings, conversely, eschew the very possibility of unified or contained meaning. They are bricolages of art-historical images taken from sources as diverse as the Dreamings of Jagamara or Emily Kame Kngwarreye, to the spots of Sigmar Polke or the hulking figures of Georg Baselitz, which Tillers combines and overlays with fragmented excerpts of text on grids made up of small canvas boards.

The paintings included here are records of a complex process of artistic negotiation, which was inaugurated in 1985 when Tillers, ignorant of Aboriginal law, appropriated Jagamara’s Dreaming designs without permission for his painting The Nine Shots. Following this initial offence, curator and mutual friend Michael Eather proposed that they resolve the misunderstanding by working together. The result was 13 paintings made over a 12-year period, which formed the core of ‘The Loaded Ground’.

Tillers’ process is relatively straightforward: he packs up the canvas boards and mails them to Eather’s studio in Queensland where Jagamara visits to paint. Sometimes Jagamara starts the painting; at other times, it is Tillers. There is, however, an apparent lopsidedness to the collaboration in that it seems to be played out almost exclusively on Tillers’ own terms: the paintings consistently adhere to his compositional structure of the grid made up of canvas boards numbered one to infinity, and which form part of his larger project the ‘Book of Power’ (1981–ongoing). Moreover, Tillers’ method of using masking tape to block out fragments of text means that when the tape is carefully peeled off at the end of the painting process, his words magically reveal themselves by cutting straight down to the ground layer of paint. This simple technique takes on a certain violence when it distorts Jagamara’s designs in that it can appear to directly echo traditional colonial hierarchies. Yet while this process of masking and peeling seems uncompromising as a collaborative gesture, it creates a greater push and pull on the surface of the painting – an unrelenting gestalt between figure and ground (as well as, importantly, word).

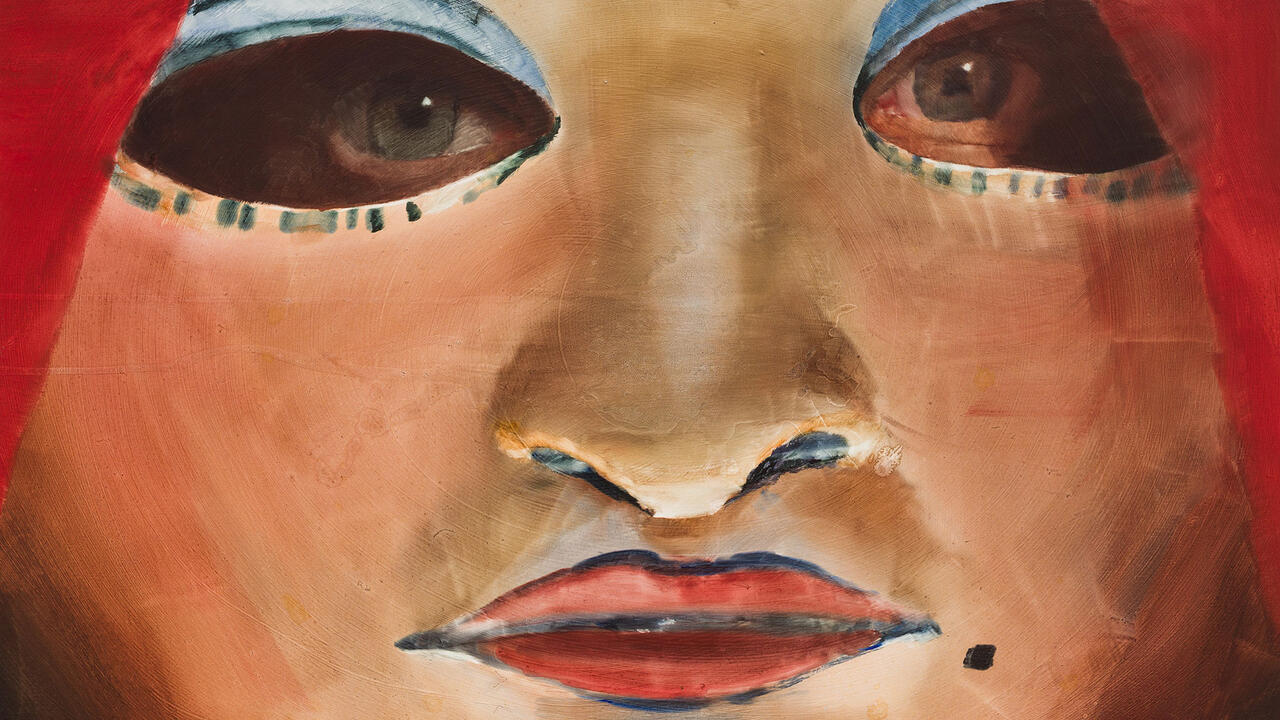

Fatherland (2008) demonstrates this well. Spread across a 90-canvas grid primed with a layer of soft twilight tones in gouache and acrylic paint, Tillers’ appropriation of a slumping Baselitz figure and his shards of fragmented text jostle with Jagamara’s red and yellow possum tracks, lightning designs and Yam Dreamings. While both painting styles eschew any sense of traditional Western perspective, there remains a striking incongruity. Ultimately, however, it is Tillers’ words like ‘Pikilyi’ and ‘obliterated’, alongside phrases such as ‘like a dream like a vision’, that float on the surface in spectral white hues: a final veil that invites the painting’s semiotic deconstruction.

The cross-cultural collaboration of ‘The Loaded Ground’ takes place against the backdrop of reconciliation in Australia. As such, the paintings are poised to become metonyms for a vast swathe of issues ranging from the aesthetic and discursive, to the cultural, political and ethical. Yet to read the paintings as a mere extension of the reconciliatory agenda – or in the framework of colonial logic – would be to ghettoize the conceptual projects of each artist into the closed categories already carved out by cultural diplomacy. It is an inherently unstable relationship between image, meaning and ownership that flickers on the surface of these paintings, knowingly agitating against the pretensions of the grid. Their value, then, lies in their ability to hold together two visualtraditions in such an ambiguous and unresolved state.