Nowhere to Run

The 1997 Whitney Biennial

The 1997 Whitney Biennial

The Mother Ship failed to reveal itself again last night, even though it was promised. Comet Hale-Bopp is at its perihelion, and here I am on the floor in a rented house. I think I may have been a little unwise to join this outfit, even though it rid me of all the old uncertainties. Dearie me, I'm starting to drift - it must be the pills and the booze. Pictures, floating into my mind... They say everything swims before you, don't they, when you're going. Soon I'll be gone. I see the city with cotton-wool clouds belching from the chimneys and the traffic heading out on a long, long highway going straight across the desert. It looks like a Barnett Newman painting from up here. I see the seasons change, fog rising from the snow on the pines, the first thaw. Rorschach pictures in the bark of trees, the undergrowth sliding in and out of focus. The corn heavy on the stem, shells on the beach and a moth on the wall. I shall miss all this. I can see Mum and Dad and little Sis, and a chimp running back and forth in a fenced-off compound. I hear elevator music: going up, going down. Everything is happening in slow motion, and in period costume. The triangle of purple cloth over my face has become a piece of Puerto Rican lace, crocheted into a map of the world. I'm peering through the holes between Madagascar and Ceylon. I see a black man kicking a pail around his neighbourhood in dead of night, and a carriage taking Marie-Antoinette off to the scaffold. This is scary; Planet Earth turns out to be made of pink Plasticine, while I'm on a bar stool, gouging at it with my spatula, moulding little gobbets of it into the shape of humans, then pressing them back into the surface again. Maybe I'm God. It's funny, it feels like Christmas. Heaven's Gate, is this it?

Father Christmas is in his den, playing games with his little helpers. Bare-arsed Santa, coming down the stairs, 'Ho, Ho, Ho', with a funnel and gallons of chocolate sauce and that look in his eye. The old atavist, up to his tricks again. A red-faced belligerent, orchestrating something nasty in his Hershey-smeared shack.

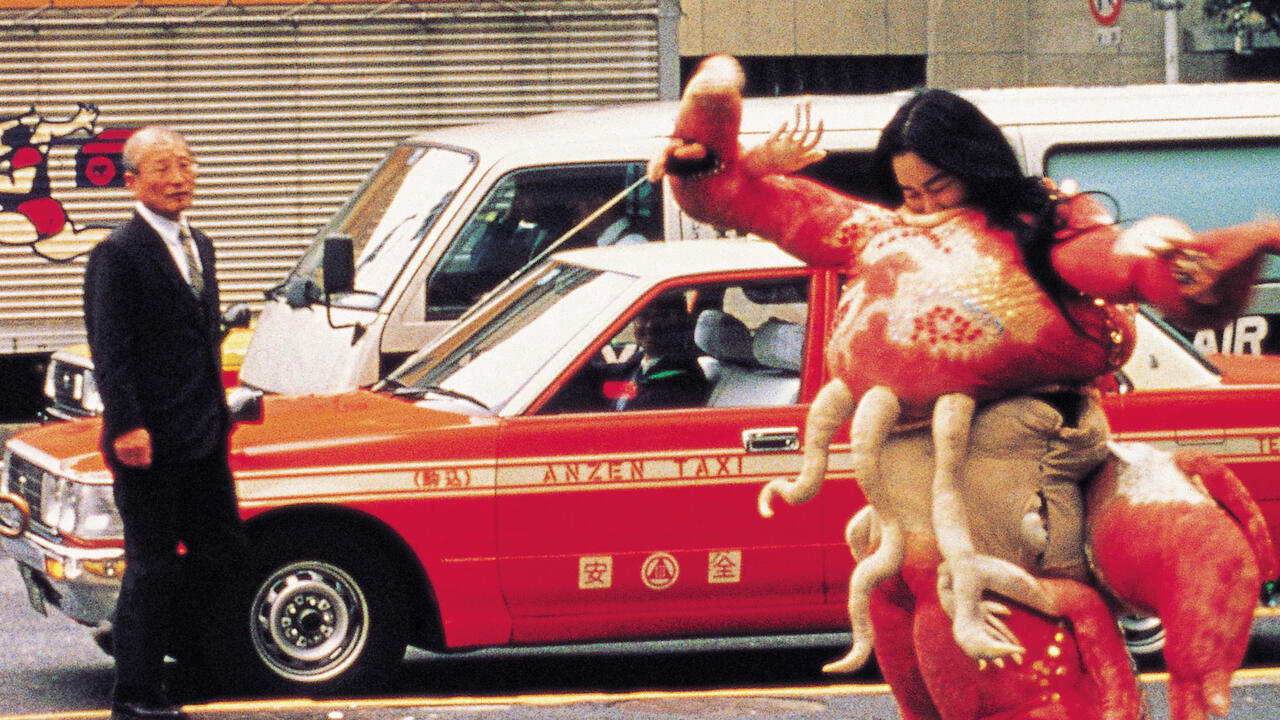

Cue gurgling and gagging and off-screen retching. Noises-off, wonky camera angles, muffled commands and someone in a rubber mask crawling round the floor. Paul McCarthy's unseasonal panto provides a dark prelude to the 1997 Whitney Biennial, curated by Louise Neri, US editor of Parkett, and Lisa Phillips of the Whitney Museum. Under-fives would do well to steer clear of Santa's festive grotto if they want to keep their illusions intact; the rest of us, with few illusions left to lose, are unlikely to be shocked.

McCarthy parodies the dumbing-down and degradation of modern life, showing individuals and their relationships on the slide from humanity to inanity. His whole act is a ruined childhood, repeated, again and again, throughout his work. Amusing though he often is, McCarthy doesn't exactly have a light touch, always taking things to an infantile extreme. His obligatory jokes-too-far, his buffoonery, are no laughing matter. It is all extremely painful, achieving a level of crassness intended, I presume, as some kind of burlesque assault on commercial culture.

But what we would like, generously, to see as critique of one sort or another, all too often gets confused with the thing it is trying to attack, deluding itself that it is actually subversive. The tragic tales told by Tony Oursler's weird and winsome talking heads invite our complicity, our sympathy, our empathy, but sometimes we still end up laughing at them, as though they were a freak show. When Katy Schimert, in a work titled The Oedipal Blind Spot (1997), writes on the wall that 'The mouth drools darkness into the ear that mutters to the mind about a murder of origin and body of desire', we can only hope that she isn't being serious. But do we know what serious is any more. How can we tell?

This is the tragedy of modern art, and one that can easily turn into farce in a show as big and unwieldy as the Whitney Biennial. It tries, inevitably, to do too much. But it is a significant event, and those forming the lines around the block at the opening surely hadn't come merely to carp as they queued for a gratis bottle of Beck's famous diuretic beer.

Including around 70 individual artists working in just about every feasible medium, with hours of film, video and live performance to take in on top of the gallery displays, this Biennial is a checklist of everything: the cosmos, nature, the individual and the group, the human psyche, sex, memories and personal histories, dreams, mad science and metaphysics, costume dramas, the anonymity and alienation of present day urban life. But always - to the credit of Neri and Phillips - we are returned to the individual outlook of the artist, the view from inside.

The curators, in a conversation which stands as a catalogue introduction, talk about art as a 'sanctuary of the imagination ... a place between the self and the world that the viewer can enter too'. In Neri's terms this is a place 'that affirms the humanistic importance of storytelling'. Uttering such sentiments without embarrassment is brave - whether or not they are true, and whether or not the language jars - but not all stories are worth telling or worth listening to, unless, like a shrink or a critic, one is paid to attend to them.

Expatriate Englishman Matthew Ritchie has written a screed of cosmic new-age drivel on the wall next to his peculiar, diagrammatic paintings, but rounds off his text with the proviso, 'If you believe that, you'll believe anything'. Oh, but people do believe anything, as the sales of all those 'Heal Your Life' manuals undoubtedly testify. Ritchie's paintings seem to present an all-encompassing world view. The sneaking suspicion that none of it adds up to very much, and that these might not be very interesting as paintings, is less to the point than the display of the man's imagination; the complexity of his mental architecture is all.

Much of the work in the Biennial - which is, after all, a touchstone of the diversity of the American artistic psyche - leaves us with the sense that modern living, let alone art, is too complex to be made sense of, except by way of fictional narratives, or in fragments and glimpses. In this regard, stories are more useful than theories, but states of mind, conditions, moments, scraps of experience, an enigmatic or poetic image (rather than the complete poem, or an entire novel) are the likely starting points for a work, and are more memorable for the viewer than the whole story. Louise Bourgeois' old frocks and scarves, dragged out and hung up as part of her latest, terrifying sculptures, stick in the mind as much as her copulating, headless woollen couple, or her soft, woven and patched torso-dolls; John Shabel's stilled, telephoto glimpses of the anonymous passengers on a plane, framed in their cameo portholes as they wait for take-off; Zoe Leonard's fake photo-album of an invented black singer and actress, presenting a life that never was - picnics and performances that didn't happen, happy couples that never were - all these objects and images beg rather than tell stories, and are the more redolent for what is left unstated. The amassed evidence of small incidents and trifles - chance encounters, views of a city, glimpses of other lives, small corners and details - this, surely, among the souvenirs and snapshots, is where the stories begin to unfold.

Artists don't just create objects or paintings or fictions, they create themselves. And we, almost inevitably, try to imagine the life behind the work, even though the fictive author we're creating is never who we think it is. Jason Rhoades, for example, comes on as a mad inventor, the kind of guy who'll come around to fix your washing machine and leave you with an automatic, windmill-driven sheep-shearing machine that glows in the dark and plays the Moonlight Sonata, when all you really wanted was a washer changing and a new pump.

His installation is a huge stockpile of home-made and catalogue-bought hardware, filling a long cul-de-sac. What is it all for? No one knows, except Rhoades. We walk round the perimeter, disentangling details from amongst the seaweed of electric cables, the piles of junk, the drums of chemicals, the pipes, lumps of extruded foam, the band-saw, the home-made wooden computer keyboard, the cardboard bazooka, the smoke machine and the disco lighting system. Sometimes the lights flash on and off, the mirror-ball spangles the walls and smoke fills the air. It feels like a party, but nobody's dancing.

Chris Burden spent five years completing his vast table-top Pizza City (1991-96), one of the main attractions of the Biennial and, in its way, one of the least assuming. If Burden weren't an artist, he'd be regarded, from this work, as one of those dysfunctional reclusive types who undertake some nerdy, grandiose project in the back bedroom, to keep the lonely mind from thoughts of sex, to stand in for human relationships and to create an illusory sense of power and control in an altogether too hostile world.

Burden's toy city has a harbour, an airport, highways, an industrial zone, a business centre, wealthy hill-top suburbs. It is astonishing, with unending, captivating little details. A torpedo is coursing across the harbour and a paddle-steamer floundering in the spume of a wonderfully articulated scrap of bubble-wrap; there's a military stand-off beside an Iraqi airliner at the airport; a happy caravanner sunbathing on a cork bluff, and traffic heading out of town. Pizza City is everywhere and nowhere, a city built out of other cities, a conglomeration whose coherence seems complete until we start to compare one street with another, the scale of one building with the next, or notice that the Lloyd's building and the Empire State are in the same town, along with oast-houses and Swiss chalets, and that the Iraqi plane shares the runway with a Stealth bomber and Concorde.

Ilya Kabakov's life-size reconstruction of a therapy unit in a Russian hospital, a line of 'treatment rooms' behind the creaking doors lining a long corridor, is no less meticulous. His installation isn't much different from interactive real-life history exhibits that museums build in order to make the past more vivid and accessible. The crowds charging through it, on my last visit to the Whitney, probably came out as unenlightened as they were when they went in, except that they could say they got a feel of what Russia was like, and a glimmer of lives not so very different from their own, in another country, another time. Whether they were affected by the experience is another matter.

But the images that I want to be left with tell no story outside their own passing presence. On a screen, a tortoise sits in the grass. The tortoise is a very boring creature, and for a long time it does not move. Eventually it heaves itself up and out of the picture. The camera follows, but gives up: the animal has a long life, and we don't have time for much of it. Burt Barr's vignette of the slo-mo tortoise is followed by William Forsythe, in a beautifully shot and cut solo dance. Forsythe's ballet seems all the more explosive after the interminable interlude with that damned reptile. At the end of the dance Forsythe, with an exquisite gesture, turns to face the camera and feels the pulse in his arm. For seven minutes, life has quickened; it's time to stop. The last moments of Forsythe's performance are incredibly touching, but I can't tell you why. A third piece begins, in darkness, with a confused beat, an unsteady, jerky clattering, and the softer shushing of car tyres on the street. The image brightens up to reveal David Hammons under the streetlights, kicking a galvanised bucket around the neighbourhood - bouncing it off a wall, dribbling it across an intersection, sending it skidding and clanging by passing strangers, tapping it along the sidewalk, finally flipping it up and into his hands. He ends with a smile.

Oddly, no one has started up a cult focusing on the redemptive powers of contemporary art. Unless, of course, they have, and we're all already in it. But instead of beguiling, confusing and deluding us with stories about benevolent aliens, or telling us there's an escape from the wretchedness of earth-bound life (or even from ordinary human unhappiness), the best art tells us nothing about anywhere else except where we are, here and now. There's no story other than the one we're in, nowhere else to go.

It's getting dark. That euphoric feeling I had earlier has worn off. I can hear an old Appalachian tune played on a steel guitar. I think it's called 'The End of the World', odd for such a jaunty memory, and strange too that it's just a good-ole-boy and his slide. I expected angels, or some telepathic call. Someone called Bruce Nauman recorded it, and put moving pictures of the guy playing the guitar in a little black room at the top of a building, where lots of people would come especially to see it. This and lots of other things - the pictures of growing up in Watts; some photographs kids took of their dreams; a sanatorium for old folks where they could remember stuff; some dirty pictures that don't turn me on and a grubby old shack with a man with a beard who does a lot of grunting. And that Louise what's-her-name, the one with the dolls fucking and the old dresses. That's like ma's dressing room where I used to sneak in. It all brings back memories. But I like the paintings of the night and the stars the best. There's the comet, but it never comes any closer. If I'd known about all this before I would never have listened to all that kooky stuff about spacemen. I liked it here.