Olivia Plender

Incorporating elements from 19th-century occultism, 1950s’ trash novellas, early Socialist youth movements and the films of maverick British director Ken Russell, the work of Olivia Plender was never going to be easy to pin down. Presented over two floors of the artist-run Castlefield Gallery, her UK solo début, ‘The Medium and Daybreak’, was less of a simple introduction than a mini-retrospective – a run-through of Plender’s practice, and interests, to date.

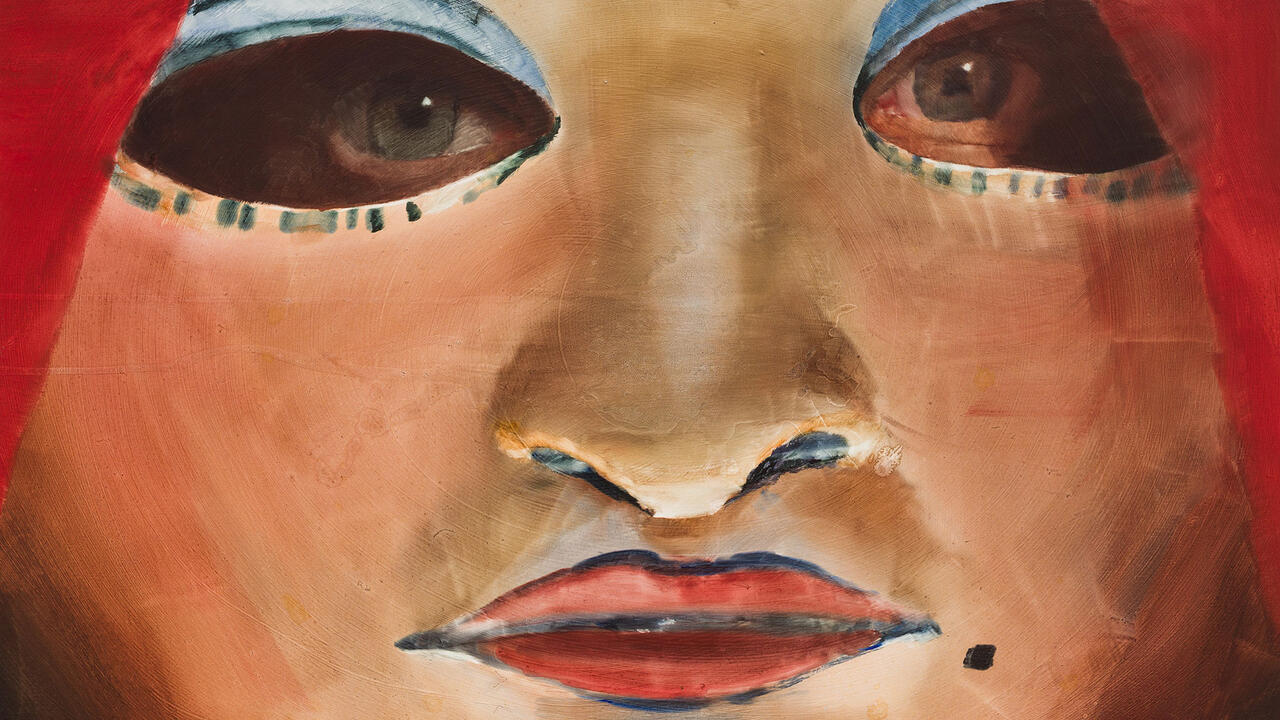

First up were her drawings: grey, spindly pencil sketches that decorate everything from posters and advertisements to the pages of her own comic book. The Masterpiece – started in 2003 and now on its fourth issue – is published in small editions, either given away for free or sold for nominal amounts. It looks like an endless sequence of images clipped from film stills, driven along by a script pulled straight from the pages of an American-style thriller. Set in the seedy underworld of postwar London, it tells the story of Nick, a hapless young painter who sets out to create the mythical art work of the title. The already fragmented storyline quickly descends into chaos, as Nick finds himself trapped in a haunted mansion with mysterious rituals going on around him.

This eeriness extended into a new installation based on research undertaken at the local Manchester People’s History Museum. In the downstairs gallery Plender recreated the interior of a spiritualist church: a monument to the 1850s, when northern England was gripped by a craze for the new religion freshly imported from America – offering believers a means to communicate with the dead. Reminiscent of a film set, or an informative historical display, the church came complete with séance table, commemorative banners and the spiritualist code pinned up on the wall. Viewers peered into the space through windows cut into the MDF construction. Plender also included a slide-show featuring photographs of the religion’s key players as well as items found during her studies.

If the chapel was Plender’s most recent quasi-sociological project, there was evidence that her investigative gaze had already been put to use earlier. A second display was based on a residency at Grizedale Arts, dedicated to the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift. This dubiously named organization was set up by a visionary socialist in the 1920s. At least, that much we learnt from an accompanying, unsigned article placed in among the other items. Described as a ‘renegade group of boy scouts’, the Kindred apparently organized campfire trips to the countryside, sanctioning back-to-nature ideals and pacifist free-living, partly in opposition to the military-style activities of Robert Baden-Powell.

Plender went to some lengths to try and get viewers to imagine what such a grouping would have been like. She showed old photographs of the Kindred, alongside reconstructions of the costumes they wore – designs based on Constructivist sportswear, topped with colourful, pointed felt caps – as well as ceremonial flags and a photocopied handbook with illustrations drawn by the movement’s leader, John Hargrave. Three of the photographs looked conspicuously contemporary: a group of figures walking along a village road, wearing the costumes and merrily waving banners in the air; documentation from an event organized by Plender at Grizedale Arts in September this year.

Jaded Modernism, US spiritualist invasions, representations of old-fashioned

artistic ideals: it all sounded like an intriguing prospect. While many artists have recently relied squarely on the 1960s and ’70s for their reference points, Plender seems to be intent on looking back even further for inspiration. Quite what was the purpose of all her activities, however, was difficult to ascertain. The Kindred could be interpreted as proto-hippies, an early premonition of what was to come, but also as a stirring example of the avant-garde merging into a form of grassroots activism. Likewise, enthusiasts claim that The Masterpiece is a project that ‘questions the making of art’, but it could equally be seen as a vehicle for the artist’s elegant and decorative designs.

Whether Plender is conjuring up forgotten chapters from the past or reinstating the reputation of the more recently marginalized – designing posters for a public interview with Ken Russell, for example – her work points to a world in which culture is constantly being lost, forsaken and often just a short library trip away from being rediscovered. Religious fervour, heroic struggle and single-minded idealism have all taken a bashing in art over the last 50 years; whether or not that is a good or bad thing is a matter of conjecture. Perhaps Plender will start a fanzine on the subject.