Watch This Space

This North West regional showcase comprised video and computer installations, with most having a flexibly interpreted idea of interactivity. It seems fair, then, to mention the gallery's highly interactive visitors' book, in which Liverpool's finest contributed their comments. These were unambiguously clear, ranging from E. Orme's 'Bollocks' through to Conni's 'Brillont' (sic), with the critical relativist midground represented by Eva Grindley's 'OK but my brother thinks its crap'.

Tending slightly more towards the bollocks rather than the brillont end of the scale was Michelle Wardle's intellectually decorative Object of Enquiry (1996). This consisted of a table behind which was projected an image of a hand-crafted bowl. Sewn onto the tablecloth, in beaded braille, was a text by Walter Benjamin (the famous blind bowlmaker), and elsewhere completely hidden beneath more braille were buttons which, if found by some fluke, engaged the projected image. Meanwhile, the image of the bowl presented and re-presented itself in differing perspectives in an unstated and disordered relationship with the participant, and in apparent indifference to the buttons pressed: disordering being the point. The artist's statement that the work encouraged engagement was, simply, untrue. The table-cloth remained pristine and unsoiled by the patina of human oils that one would expect from use by the usually button-happy E. Ormes, Connis and greasy frieze reviewers trailing through the gallery, now all traumatised by the painful artschoolness of this work and its dispiriting neglect of their interactive rights.

In contrast, Sera Furneaux's Kissing (1996) was extremely clear in its guidance towards involvement. The care shown to for the participant, combined with the work's shameless technical perfection (as opposed to the usual mock low tech), displayed an unusual concept of service which was surprising in its plain-dealing humility. The work comprised a sort of photo booth, called a 'kissing booth', where participants chose from an image database of others offering a kiss, and responded with their own. Beautifully pixellated, large scale images were then projected outside the booth, each in two second bites repeated six times. The choice of image to view was made using a touch sensitive screen, and this partly created the Disneyland Syndrome inherent in such art: the need to wait in turn. Overall, the effect was somewhere between Dick Jewell's Found Photos book of photo-booth images, and a super-large episcope projection. Kissing was sometimes beautiful, moving and funny, combining the sincere kisses offered with the high octane, anarchic contributions of Liverpool's genius, art-loving public. The booth scored about one kiss in five, the rest being raspberries blown at the camera, inane grins, earholes disappearing off screen as the Bash Street Kids fumbled in the booth, and the occasional mouthed obscenity offered as art criticism in the field.

Recipricocity and interactivity between contributors was lacking though, in spite of the artist's claimed intentions. The linear presentation, on one screen only, disallowed comparison or a sense of mutuality. However, the work was principally as interesting as the people in it, who, however, were very interesting. The human face is the most intriguing visual phenomena there is to other humans, and, in this sense, Kissing occupied the place traditionally occupied by portrait painting its delicate choices of image duration and repetition succeeding as a Bruegel might have. In the visitors book, the perceptive L. Scanlon described Kissing as 'FUN TO WATCH! NO BRAIN, NO IDEAS', which was a great compliment, when the concepts and conceits of current art practice regularly share a similar role to decorative paintings or baubles on mantelpieces.

Stephen Paul Connah's Breathless (1996) was slightly over self-importantly theatrical. Its interest in depictions of violence took the form of extremely transient images of the artist apparently restaging street killings as photographed by Weegee. These were shown before a projection onto a rag of the artist exhaling heavily, whose recording process had introduced a sibilant distortion into the soundtrack. Broken Toy (1996-97), comprising a disassembled TV corresponding to the crawling articulation of head, torso and legs of a child, was more interesting though. The head (the cathode tube) showed an infant's face responding in distress to trauma. Slowed down, the pitch of the child's wail was lowered until it became an adult's. Broken Toy's anthropomorphism introduced a conflict between an impulse towards parental care in the viewer and indifference to the insensate electro-gubbins of the TV.

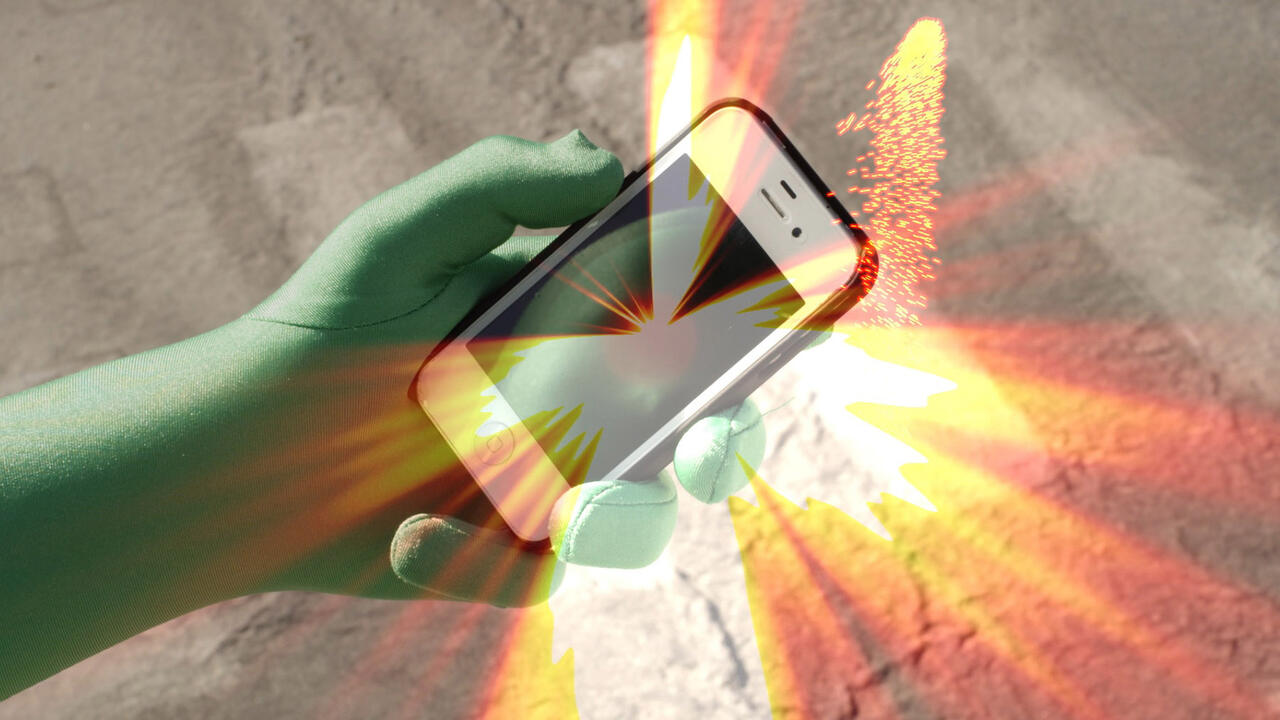

Finally, Katherine Moonan defiantly made a computer game installation, PC World (1996), in which there was, literally, nothing to play or interact with, and about whose legitimate target the sexualising of masculine techno-aggression it seems there's not much new to say; although a good deal of text was taken up by Moonan not saying it. Back-lit paper images of manufacturer's games characters and their ludicrous sales texts were faced by peno-centric, soft fabric control devices: floppy stitched satin games consoles, flaccid pink guns and limp joysticks. These, with names like 'Thrust Master' and 'Super Warrior', naturally failed to thrust or otherwise perform in the usually predictable manner. The male dominance impulse safely tamed by Moonan's didactic, static display, the streets of Liverpool may now be safe enough for Barbie Dolls to enjoy without harassment.