Art Weekender – Bristol and Bath

What was once – last year in fact, on its first outing – known as Bristol Art Weekender, this year, became Art Weekender Bristol and Bath. I can’t help wonder about this sudden merging of the two cities, especially given their divergent art scenes. It has the whiff, perhaps inevitably, of a short cut rather than a genuinely collaborative undertaking, which is a shame because overall the event felt stretched and unevenly spread as a result. Bristol to Bath: Life Drawing on Trains (2015), a drop-in event run by Bath Artists’ Studios, attempted to bridge the gap between the two cities. Though if, like me, you wanted to catch as many as possible of the 50 plus events happening over the weekend, a car was the only way to do it.

What was once – last year in fact, on its first outing – known as Bristol Art Weekender, this year, became Art Weekender Bristol and Bath. I can’t help wonder about this sudden merging of the two cities, especially given their divergent art scenes. It has the whiff, perhaps inevitably, of a short cut rather than a genuinely collaborative undertaking, which is a shame because overall the event felt stretched and unevenly spread as a result. Bristol to Bath: Life Drawing on Trains (2015), a drop-in event run by Bath Artists’ Studios, attempted to bridge the gap between the two cities. Though if, like me, you wanted to catch as many as possible of the 50 plus events happening over the weekend, a car was the only way to do it.

Situations, the organization that runs the Art Weekender, also produced the most heavily publicized event of the weekend: Sanctum (2015), Theaster Gates’s long awaited first public project in the UK. Within Temple Church – a little known, bombed-out ruin in the heart of Bristol – Gates has assembled a chapel-like structure. This is a simple and homely thing, a peaked hodgepodge of reclaimed materials, mainly timber, sourced in and around the city; its aesthetic has something of the up-scaled allotment-chic. The project, which runs for 24 days and will be open 24 hours a day, will see over 550 hours of continuous performance. But its scale and ambition – as well as the accompanying glamour and press coverage – risk dwarfing the rest of the Weekender. The intentions behind Sanctum are honourable: to gather together the city’s physical materials and its citizen’s voices, and to provide a focus on inclusive and unexpected encounter (since the line up is a secret). But, as is so often the case, when you take the theory off the page and into the real world, the ethos doesn’t quite translate. Over the time that I spent there, the extended overlaps and patchy performances felt like an average open mic session rather than anything transcendent, transformatory and thought provoking.

‘Amalgams’, 2015, documentation of performance. Photograph: Max McClure

But the Weekender wasn’t all about Sanctum. In fact, a stone’s throw away from Temple Church, Britain’s oldest Methodist church played host to another artist’s takeover on Saturday night. ‘Amalgams’ curated by Sam Francis, Rhiannon Jones and Benjamin Owen (as part of the sound and image collective Onomato), filled the small candlelit John Wesley chapel with sonorous improvised choral, electronic and instrumental textures alongside and in response to experimental film. The films and performers were positioned in various corners of the space, inviting you to explore it. I’d seen and enjoyed a number of the films before, but newness wasn’t the point here. In fact the works I had seen, such as Louisa Fairclough’s Bore Song (2011) and Rod Maclachlan’s Paint Can (2008), were heightened by the hushed atmosphere, darkened space and surrounding soundscape. What particularly marked the evening out was its low-key and considered intimacy; its slowly unfolding rhythm was a quiet challenge to traditional structural relationships between film, sound and art installation.

Holly Davey, Here Is Where We Met, 2015. Photograph: Max McClure

This is the kind of event that Weekenders are made for: experimental and artist-initiated performances or installations in unusual spaces. Here is Where We Met (2015), a newly-commissioned sound installation set in the hidden, disused and overgrown Cleveland Pools in Bath, then, had all the ingredients to be a success. Except that it wasn’t. Accessed by means of a steep, easy to miss pathway from the street, a sound piece emanated from a boarded-up amphitheatre-like building that framed the bigger of the former swimming pools. But the audio itself – a rather predictable nine-minute loop of the sounds of children playing, water dripping and trains rushing by – felt like a missed opportunity. What could have been an audio exploration of the pools’ nooks, crannies and stagnant water instead felt like an exercise in nostalgia.

Elsewhere, there were some interesting artist interventions within the cities’ museum collections. Alexander Stevenson’s Quilt Cowboy (2015) greeted visitors in the downstairs hallway of the house of the American Museum in Britain, near Bath. The costume is quite literally a poster boy of the American film industry, constructed from a quilted patchwork of blown up and stitched together film posters. It stands like a suit of armour next to a film showing Stevenson himself exploring the museum while wearing the quilted costume. In the film the cowboy’s movements are comically laboured, stilted and encumbered by the quilted suit’s lack of give. He is filmed drawing his quilted guns at a reflection of himself in a mirror in the museum’s New Orleans room; in another scene he stands as if cheek to cheek with a statue of Abe Lincoln and later, he disappears into the distance, romantically running over the crest of a hill in the museum’s grounds. But these stereopyical gestures are wittily undercut by the complete absence of physical threat or violence, the hallmarks of the classic Hollywood Western. In the film, the quilted cowboy feels alien, much like the museum’s extensive collection of American folk and decorative art itself, housed in a Georgian building and nestled in the very English Somerset landscape. He is out of place, like an anachronistic patchwork puppet, pictured as if seeing the world for the first time.

Alexander Stevenson, Quilt Cowboy, 2015, installation view. Photograph: Max McClure

Two evening performances, one at St George’s and one further up the hill at the Bristol Museum, were wildly different. On Saturday night Theaster Gates confounded his mainly white, middle class (and I’m guessing largely atheist) British audience by bringing American gospel tradition to what was billed as a performance lecture, belting out, in his words, ‘all the hymns that [he] could think of’. The audience was baffled: I wondered whether Gates was for real, whether to clap between songs, how long he was going to keep it up. And Gates knew it. The evening, however, wasn’t played out entirely in spiritual earnest. It was interspersed with, albeit uncertain, comedy as Gates mumbled or hummed words he couldn’t remember, or overdid his emotive delivery, shifting between musical styles from faux opera, to choral to rock and roll. He sang unaccompanied for almost an hour before gently encouraging the audience to join in, which, in the end, it did. This was one of those coming together moments, however fleeting.

In contrast, Sunday night’s lecture Cunae was led by Andy Holden and his father, Paul Holden, an ornithologist. Granted complete access to the museum’s little-explored nest collection, the duo performed a kind of straight show-and-tell round up of their interest and enthusiasm in birds and their nesting habits. The materially sensitive and complex structures of nests allowed Andy to draw a parallel with the process of making art, but the real subtext here was the relationship between father and son – of co-dependence, reciprocity and cooperation. However, Andy’s references to ‘ecological thinking’, the ‘cosmic confidence’ of nest structures described as ‘scribbles and scratches’, and ‘drawn into the trees’ felt cursory and left me wanting more.

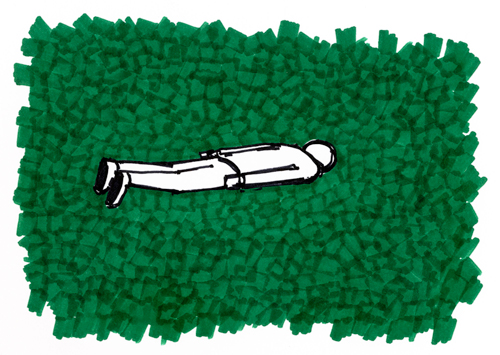

John Wood and Paul Harrison, Erdkunde: The Study of the Earth, 2015, video still

John Wood and Paul Harrison’s quirkily delivered lecture/performance, also at the Bristol Museum, on the other hand, was full of witty insight. Erdkunde: The Study of the Earth (2015) – the result of research undertaken in the museum’s geology archives – is a large-scale projected film surrounded by extensive research notes that are pinned around the gallery walls. Here the classic show-and-tell lecture format was turned upside down as the duo splintered the relationship between words and images, inducing thought through disjunction. Their work has the feel of a children’s picture book in which simple sentences accompany illustrations or actions. Erdkunde’s written captions, however, function to disconnect rather than explain. Museum labels and gallery texts, typically conceived as serious objective conveyors of information and clarification, are never neutral, as Wood and Harrison’s often comic captions make clear: ‘The most sheepish’ reads the caption as a large hand appears on screen directing our attention to the only sheep in a collection of toy animals; ‘The most important’ reads another, as that same hand points to the shorter of two pencils laid out side by side. There’s a poetry at play here. Art writers (and readers) take heed: what we choose to point out is rarely accidental; what we choose to ignore is usually deliberate. Language is loaded.