Jay DeFeo

‘Sixteen Americans’, the 1959 exhibition curated by Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is often held up as the defining exhibition of the American postwar avant-garde. Artists such as Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson and, especially, Frank Stella purged the formalism of their Abstract Expressionist predecessors of any remaining spiritual or psychological inflections, paving the way – or so the story goes – for Minimalism and Conceptual art. But that’s never been the whole narrative of American art. In fact, it wasn’t even the whole story of ‘Sixteen Americans’. That exhibition also included an unjustly overshadowed artist from San Francisco, Jay DeFeo, whose wholly different approach – expressionistic, literary, allusive and deeply emotional – was finally on full view in this first-ever retrospective. (Although this exhibition was organized by the Whitney, it was initially staged at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art last year.)

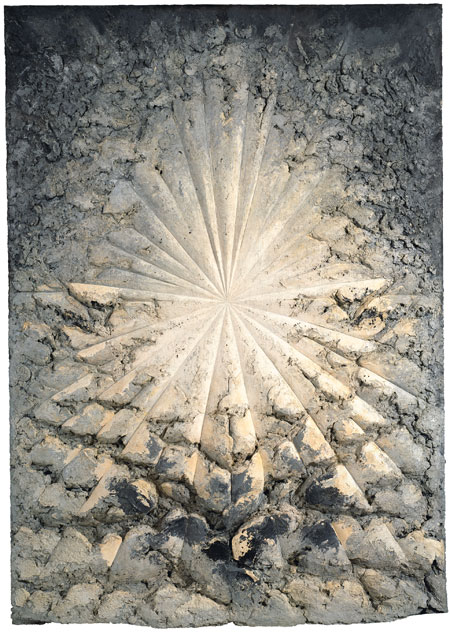

DeFeo, if she’s known at all these days, is remembered for just one work: her Brobdingnagian painting The Rose, now in the Whitney’s permanent collection. Absurd and magisterial by turns, weighing more than a tonne, it’s as much a sculpture as a painting – as the white impasto got thicker and thicker, up to a foot deep towards the bottom, she carved the pigment with a chisel to produce a radiating botanical form. DeFeo worked on The Rose for eight years, from 1958 to 1966, and might have gone on longer had she not been evicted from her apartment. The painting had to be removed via forklift; as fellow San Francisco artist Bruce Conner documented in a revealing 1967 film, The White Rose, the movers had to excise a window of her building to haul the painting out.

The exhibition catalogue includes photographs of DeFeo posing nude in front of the in-progress Rose, arms outstretched and with a Hebrew letter superimposed on her chest, in case you doubted her spiritual rhetoric. Yet to my eye The Rose is more successful as a marker of an artist’s single-mindedness than as a standalone art work, and the Whitney’s over-the-top presentation of the painting – in its own black gallery and illuminated by spotlights – seemed to confirm that DeFeo’s chef-d’œuvre asks to be venerated like a holy relic rather than beheld as an autonomous painting. So the true value of this exhibition was its expansion of the terrain of DeFeo’s career, and the isolation of The Rose in its own gallery made it possible to look at her other, more engaging work from that period with full attention. Intricate paintings such as Origin (1956) and The Verónica (1957), both of which were included in ‘Sixteen Americans’, recall informel painting of the time with their limited range of colour and flowing, protruding marks. And large, swooping drawings like The Eyes (1958) reminded me of such psychologically engaged Modernists as Louise Bourgeois and Lee Bontecou, not the sort of figures I’d put alongside the vainglorious Rose.

DeFeo’s work from the 1970s and early ’80s, almost unknown before this retrospective, displays less intensity than her early work but may be more rewarding for that. Her first paintings after The Rose depicted, of all things, a dental bridge composed of her own teeth and false ones. ‘My model … out of my own head!’, reads a caption she typed on one 1971 study and, indeed, the teeth works can be thought of as both a surreal repurposing of an everyday item and an index of one of her recurrent illnesses; DeFeo suffered from periodontitis, allegedly from inhaling chemicals while making The Rose. She also worked in photocollage, sometimes featuring the dental bridge, as well as more traditional black and white photography. (I liked one adorable shot of her dog, named R. Mutt, a perfect collision of the canine and the Duchampian.) Later graphite drawings, of swimming goggles or a camera tripod, exhibit much more delicacy than the earlier, more expressionistic work – and the imagery’s iteration over half a dozen or more drawings only amplifies its oddity.

In her last years, having been diagnosed with lung cancer, she turned to producing small and delicate linen paintings composed of a narrow palette of greys and beiges, as well as modest drawings torn from a spiral notebook, some as simple as an ellipse and a check mark in a sea of white. These last works lack the energy of her early paintings or the weirdness of her 1970s output – but that almost didn’t matter at the end of this illuminating retrospective, which argued persuasively that DeFeo deserves to be understood for the entirety of her career. Beyond rigid formalism, and beyond New York too, dozens of stories remain to be told about the American postwar generation, and this show was a welcome contribution to that still-delayed project.