Jean-Michel Basquiat

Barbican, London, UK

Barbican, London, UK

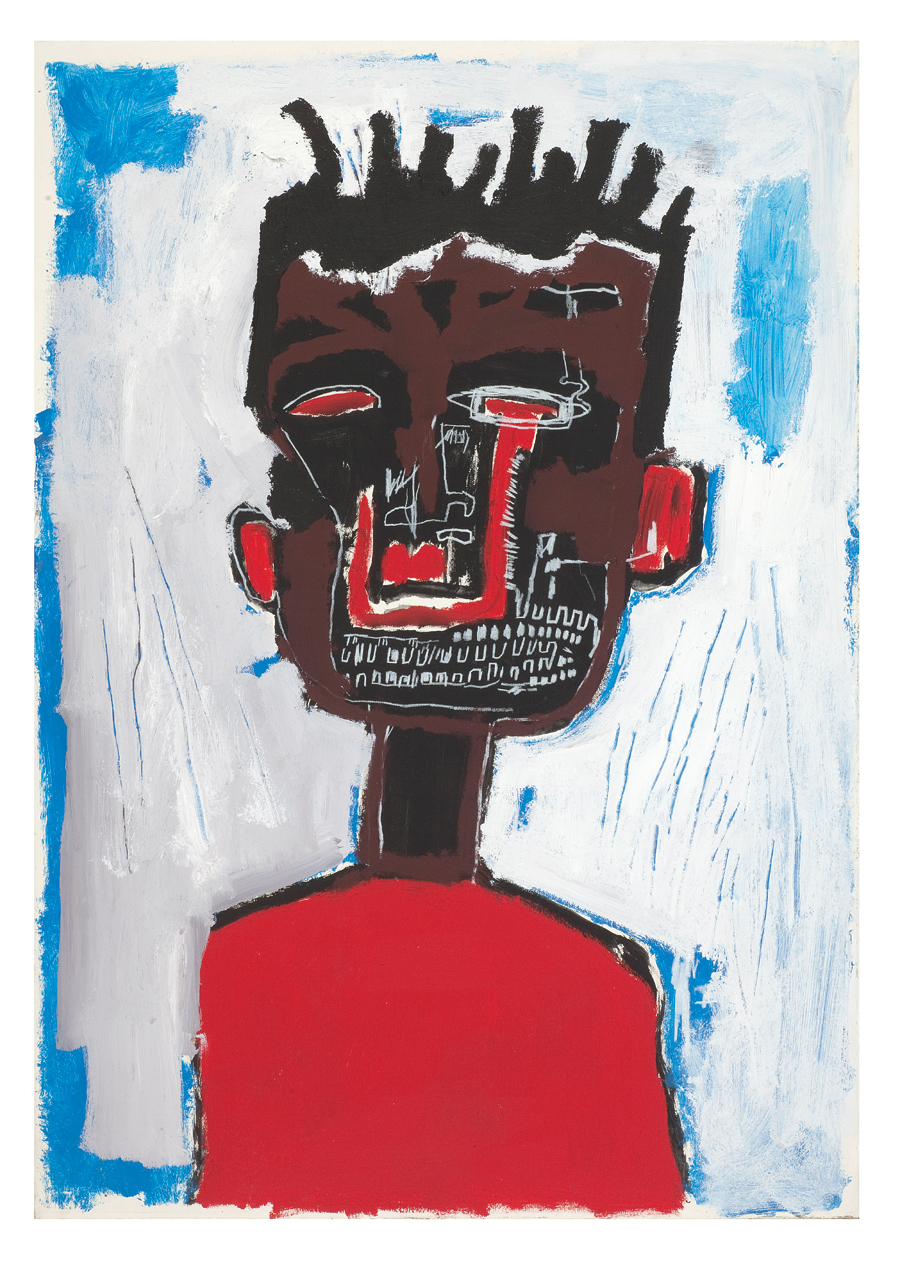

Not long before Jean-Michel Basquiat died from a drug overdose, in August 1988, aged 27, the prodigious African American painter reportedly told a friend: ‘I’m not a real person, I’m a legend.’ You don’t need to see ‘Boom for Real’, his first UK retrospective, almost 30 years later, to know this wild-eyed claim has come true. Once upon a time, he was a runaway teen who tagged SoHo by night under the prankster codename Samo; now his canvases are a symbol of drool-inducing lucre. Untitled (1982), a deranged study of a head, set an all-time auction record for a work by an American artist when it sold for USD$110.5 million at Sotheby’s New York in May. ‘Boom’ is right. Supreme and Converse have produced limited-edition swag covered in his various trademarks (crowns, masks, bones); A$AP Rocky and Jay-Z have offered shout-outs to his ghost. Phoebe Hoban’s biography of the artist, Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (1998) is so loaded with decadence and disenchantment that it frequently reads like Arthur Rimbaud’s poem, ‘A Season in Hell’ (1873) retold for the 1980s. (‘You sorcerers! I placed my treasure in your hands!’) He’s gone beyond the big time to enjoy the afterlife of a mythic character, just like his two heroes, Charlie Parker and Andy Warhol. But alongside the money and fame, there’s a whole complex of myths and demons circulating through the work. ‘Famous’ is scrawled in one painting on show from 1982, its shape reminiscent of a tombstone.

An odd curatorial lacuna means ‘Boom for Real’ tilts almost entirely towards the early part of Basquiat’s career, revealing few works created after 1985. Even if he was getting wrecked, some of the late pieces are exceptional: Eroica I (1988) with its forlorn inscription, ‘Man Dies’, looping like a chant; or Riding with Death (1988), which darkly conjures the Reaper on a skeletal horse. The paintings on show amid an awesome collection of ephemera (including such rarities as signed artwork for Rammellzee and K-Rob’s record Beat Bop, 1983) sometimes feel like background evidence used to illustrate the razzle-dazzle of Basquiat’s artfully cultivated legend. We chase the artist’s spectre from room to room, loping, super-cool, through lower Manhattan in the semi-documentary Downtown 81 (1981/2000), mumbling to Glenn O’Brien on TV Party (1979–82) or goofing around with Warhol the extraterrestrial on his knee, who chats to him as if he’s a dumb midnight cowboy: ‘What’s your last name, sweetheart?’ Such focus is a hot tribute for an artist who craved fame, studying biographies of his favourite jazz cats like religious codices: the life and work entwined in the style of some killer chimera.

Basquiat was a drug-gobbling puer aeternus but he was also a weirdly paradoxical character, undone just as much by Reaganomics permitting the byzantine trade in his paintings as by the high-grade southwest Asian heroin swamping the Lower East Side in the early 1980s. He’s the embodiment of that fabled era before the Big Apple was rotten with plutocrats, yet representative of the corporate future to come. The father-son and/or homoerotic trappings of his hook-up with Warhol still fascinate: vampire Andy was sucking young blood to survive and yet the two misfits found an eccentric kind of solace in each other.

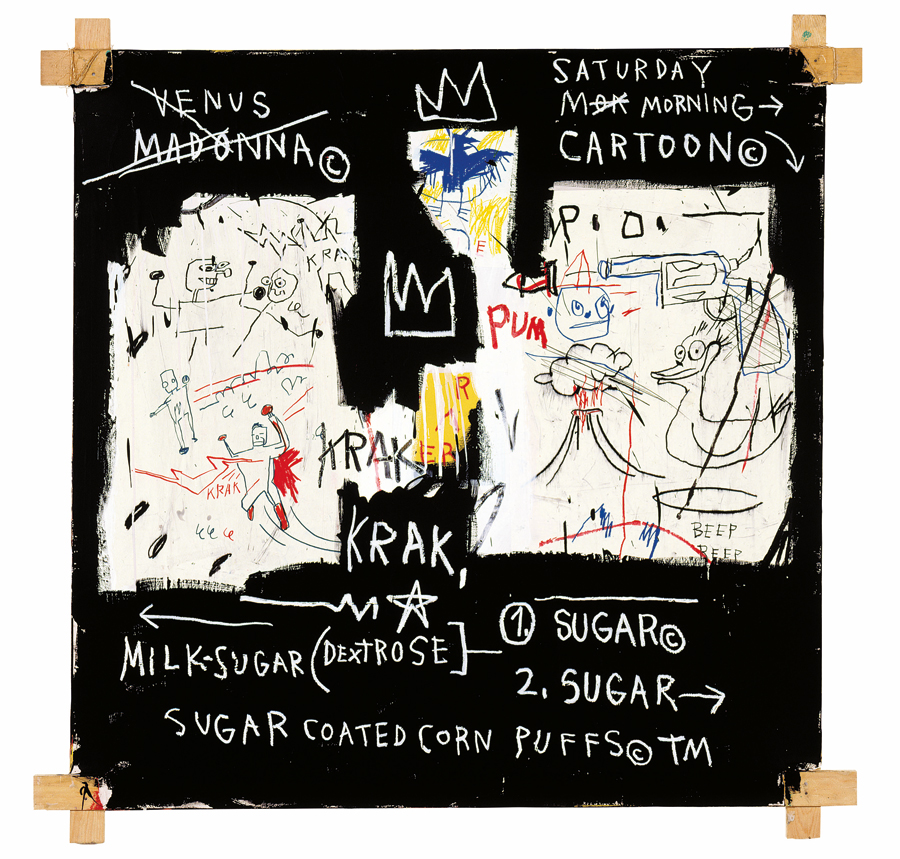

Back in 1982, the critic Rene Ricard discerned that Basquiat’s ‘earlier paintings were a logical extension of what you could do with a city wall’. His canvases are experimental zones where he explores the picture as an exploding galaxy of information (Pegasus, 1987) and the portrait as some digressive freak-out: Five Fish Species, 1983, dedicated to William Burroughs, is littered with factoids, quotations and dates drawn from the master’s dark biography. They operate like fields of strangely musical noise: words repeating, odd mixtures of art brut or antique material in duet, favourite themes (fame, death, cities, economics) resurrected or ripped apart. Skunks, leeches, Titian, boxing matches, dogs, Straight, No Chaser (1965) by Thelonious Monk, notebook scrawls about ‘the germs on a spoon behind the oven’: Basquiat turns his brain inside-out in encyclopaedic fashion. This data is also a wormhole of personal code and allusion: severed ears, the word ‘tar’, a feast of snakes hinting at poisons in his system and creeps trying to win his fortune. Sometimes he finds sucker-punch eloquence in drawing little more than a bone or tooth.

The same contrary energies are at play through his raid on art history. Basquiat figured out early that painting could be a patricidal game. (Hoban’s book seethes with his alternate bad feelings towards and eagerness to please his father.) For Untitled (World Trade Towers) (1981), he stages what he calls elsewhere ‘a flashback to his childhood files’ – revisiting the moment when he was hit by a car, aged seven – in the spirit of Cy Twombly with amphetamine psychosis. But for a few gobbets of blood-red gore, the scene is all scary monochrome: electrified Roman numerals mix with wonky alphabets and blurred shadows. Leonardo da Vinci’s Greatest Hits (1982) maims juicy parts of the genius’s back catalogue, turning the head of Vitruvian Man (1490) into a blast of static. Homage deforms into parody: wicked jokes at the expense of dead elders.

The raw facts of being the rare black kid within the white art world are also at play in his rambunctious attitude to the canon. (One creepy tidbit sees him alter a headshot of Warhol, creating Drella in blackface.) He provided acid commentary on the art world’s crook economics and ominous exclusions from the beginning. Site-specific riddles, Basquiat’s Samo graffiti comes from the same wish to unsettle or seduce the bougie crowd. A room of Henry Flynt photographs track him like a character from downtown folklore, half secret agent, half ghost, the cryptic one-liners appearing between cracked windowpanes and filthy paving slabs, words faint as ectoplasm: ‘Samo as a result of overexposure’. (Is the critic Greg Tate correct that everybody should hear ‘sambo’ stashed inside ‘Samo’, short for ‘same old shit’?) Like Warhol, Basquiat was always conscious of art’s proximity to prank. He scribbles factoids about his big daddy predecessors on brown paper for Untitled (Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Duchamp, Pollock) (1986–87), knowing his hand transforms mere art historical rehash into treasure. It indicates his typical wily self-consciousness about his status as a commodity – Basquiat garlanded his work with copyright symbols – but also his fixation on art history and whatever afterlife it assures.

Everywhere there are apprehensions of death. His final piece of graffiti reads ‘Samo is Dead’. Against the backdrop of Confederate statues crumpling on live feeds and American football players kneeling through ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’, Basquiat’s commemoration of black cultural royalty feels courageous but it’s also haunted by certain sinister phantoms. He exults Parker and Jack Johnson, the first African American heavyweight champion – dissolute figures whose self-immolating antics he purposefully mimicked. In an untitled 1982 self-portrait Basquiat pictures himself as an ogre in the boxing ring, arms raised in triumph. Haloed with thorns, the face is strange, maybe belonging to a cow stripped of its flesh or a reveler bleached white for carnival in Haiti. The next year, the face transforms into a black mask, alone in who knows what wilderness, with no substance beyond the holes signifying eyes. His dead stare is terrifying but his hyena teeth stay bared in a bloody grin. The dream of a dead future is outlined in one notebook page (‘time to Greyhound and come back a drifter’); on another ‘firecracker’ is carefully written and crossed out.

Main image: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, 1982. Courtesy: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, licensed by Artestar, New York; photograph: Studio Tromp, Rotterdam