Shop of the New

Zurich’s legendary Dada venue, Cabaret Voltaire, now includes a shop selling ‘Fair Trade’ T-shirts

Zurich’s legendary Dada venue, Cabaret Voltaire, now includes a shop selling ‘Fair Trade’ T-shirts

For your next trip to Zurich consider a visit to the Cabaret Voltaire, mythical birth-place of Dada, where artists with pointy hats and thunderous nursery rhymes changed the course of art history. The venue is now an art space dedicated to a critical Dada makeover for today’s context, located in the age-old Niederdorf neighbourhood, with its cobbled streets and antiquarian bookshops. In terms of blending in with the surroundings, you would think that Hans Arp readings and costume re-enactments would suffice. But for some years now the picturesque Old Town has been defined more and more by teenagers in Marilyn Manson T-shirts buying decaf frappuccinos or veggie falafels. A strong example of patrician solidity melting into air, of commodification forcing proto-bourgeois barbarians to capitulate – something the Dadaists might have actually applauded, simsala-booming happily away at the Starbucks staff. The cash-strapped Cabaret team, for its part, has decided to build on this and to beat gentrification at its own game by locating a T-shirt shop at the front of the space and inviting me to ‘curate’ it as part of the exhibition ‘Radical Chic’.

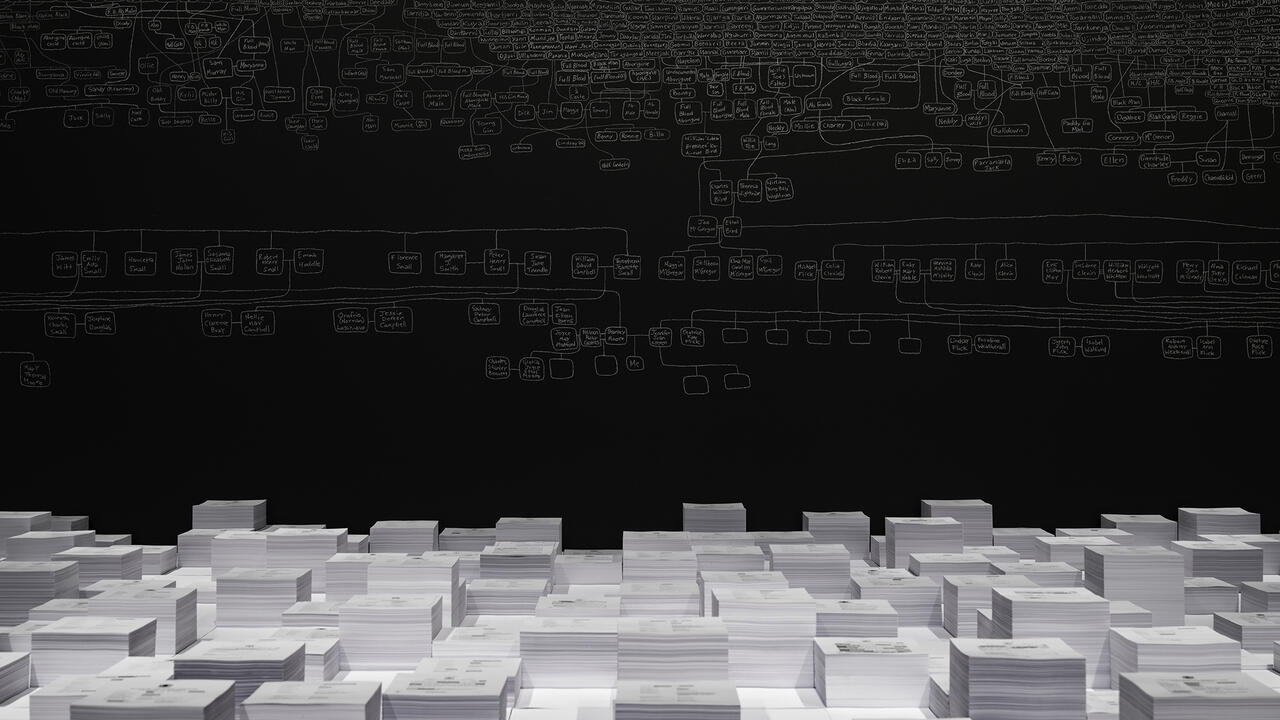

Notions of art branding and alienation-as-an-opportunity are now an integral part of post-Warholian artspeak – from the grinning apocalyptica of Boris Groys, who claims that in a ‘post-discursive’ era of total art market triumph the only way for art to be critical is to be self-reflexive as a commodity, to the various strands of palest pink Marxism like my own, focusing intently on tortured commodity fetishism discussions since the economic history and conditions of production stuff is so much harder to understand. Then you have art historian and part-time management-consultant Wolfgang Ulrich saying the only reason art has more credibility than advertising is that it has had a head-start of a couple of centuries (cf. Ulrich’s and other contributions to Art & Branding, 2006). As if to say: ‘Stop worrying about the ethics. They will go away.’ The thing is, they won’t. Not really. In his book Postproduction (2002) Nicolas Bourriaud paraphrases Liam Gillick to suggest the art-shop paragon had shifted from the 1980s’ designer store to the second-hand shop. A good point, but not quite up to date, which is why, at the Cabaret, we opted for the brand universe of ‘Fair Trade’. A goody-two-shoes, cosmopolitan, Radical Chic, educated middle-class-type thing, something much more ‘contemporary art’ than Gucci or a flea market. We offered Helvetas Fair Trade merchandising, along with art works by Christoph Büchel, Samir Felt, San Keller, Kate Rich and Superflex, and other appropriate paraphernalia, including T-shirts bearing radicalesque iconography by various artists, curators, designers and Cabaret staff.

Fair Trade relies heavily on the packaging I once termed ‘Body Shop Hermeneutics’: that flattering sense of ideological superiority through critical consumption. To generate this auratic surplus, a strict set of moralized directives addressing everything from child labour to pesticides is necessary, criteria just as misleadingly simple, and just as misleadingly redemptive as, say, ‘site-specificity’, ‘institutional critique’, ‘self-reflexivity’, ‘open-endedness’ or ‘docu-fiction’ in the arts.

Tellingly, Fair Trade is now falling victim to its own success. In their book The New Spirit of Capitalism (2006) Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello demonstrate capitalism’s aptitude for updating itself by listening closely to its harshest critics, which is why today the enduring misery can easily be contained, thanks to the notion that we live in a society that is dynamic, creative, tolerant, self-critical, free and authentic. Turning to the Fair Trade phenomenon, the authors argue that its recent loss in market appeal lies not in the occasional scandals revealing fair-play deficits but precisely in its standardization and profitability. Since authenticity is traditionally defined as that which is done without ulterior motives and which transcends calculation and self-interest, the challenge for Fair Trade is to prove that profit and sincerity aren’t mutually exclusive.

But what it lacks in ‘earnestness’ it makes up for in ease. Fair Trade is absolutely painless. Everybody wins. Fair Trade corporation Max Havelaar brandishes Un plus pour chacun – ‘a plus for everyone’ – as its slogan and is named after a 19th-century Dutch emissary in Indonesia who struggled not for decolonization but for an enlightened type of empire. Critique without conflict, profit without exploitation, solidarity without wasting time. This is the ‘binary fluffing’ inherent in every tradition appealing to ‘ambiguity’ as a high value, from advertising (Marlboro is familiar and outlandish, relaxing and wild) to artspeak (Mike Kelley is patently opaque, intricately simple). Politically, what emerges from the fluffing is the redemptive promise that if only we were more ‘fair’ and ‘critical’ in our consumer habits, painful questions of redistribution and political justice would be unnecessary.

Tirdad Zolghadr is a critic and curator based in Zurich.