Stephen Lapthisophon

Gallery 400, Chicago, USA

Gallery 400, Chicago, USA

Stephen Lapthisophon begins an essay accompanying his installation with the words 'I can't read my own writing'. This declaration could be read as an existential realization of self-alienation ('I am so depressed I can't trust what I say') or as a Postmodern admission of the failure of originality. Such self-reflexivity has always been part of Lapthisophon's ongoing investigation of language and art history through the constraints of Modernist ideology. But now this statement has taken on a new meaning; Lapthisophon has become legally blind, so he literally cannot read his own writing. For a visual artist and writer, losing the ability to see is a daunting challenge, to say the least. 'With Reasonable Accommodation' is, on one level, Lapthisophon's rumination on becoming what Americans have established under the law as 'disabled', and on another level, a loose metaphoric saunter through Modernism's doomed utopia, in which physical fitness and aesthetic rigour would cure all social ills.

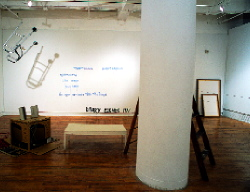

At first glance the installation looked unfinished. The space was littered with ladders, a couple of benches, strange ramps, cardboard boxes, coiled and dangling electrical cords, a blank blackboard, and photocopies and web print-outs taped to the walls. But after circumnavigating this conglomeration of stuff for a while, layers of meanings, allusions and associations began to accumulate. 'With Reasonable Accommodation' was more a weird obstacle course, resisting any single coherent reading; a scatter-art strategy that became increasingly logical. It was meant to simulate Lapthisophon's experience of frustration and discovery trying to figure out a new normalcy of blindness within the given constrictions of the non-impaired. An 'Information' sign dangled near the ceiling, divorced from any potential to make good its offer. In a cordoned-off corner a couple of paintings were leaning with their faces to the wall - access denied - near a small colour copy of a painting positioned just far enough away to be illegible. Cassette players emitted sounds that were garbled and barely audible. In the back cupboard Lapth-isophon shoved a bunch of crutches near the emergency exit.

These prosthetics are extensions of the human body to substitute for loss and improve mobility. By adding art-historical references to them, Lapthisophon suggests that modern art itself is an ameliatory device. A walking frame hanging from the ceiling recalled Marcel Duchamp's hat-rack ready-made, literalizing this earlier artist's conceptual leap into an aid for disabled bodies. The Arts and Crafts ideal that healthy bodies yield healthy minds was represented by a Frank Lloyd Wright table and a book by American theorist Roy Croft. Lapthisophon introduced the utopian urge of documentary/art photography with a degraded blow-up of Paul Strand's famous picture of a woman with a sign hung around her neck that reads 'blind'. Elsewhere, a tiny copy of a painting of Milton depicted the blind poet dictating to his daughter, a literary romanticizing of disabled-ness, that blinding light of transcendence.

This swirl of art allusions embodied in physical obstacles also included a bright Ellsworth Kelly-green ramp, shaped like a Robert Morris Minimal sculpture. Its shape taken from a wheelchair access ramp, the object was placed so that it led smack into a wall. Lapthisophon took Andy Warhol's (also appropriated) dance steps, re-placing them on the floor, but so near a large pillar that any potential dancer would be in physical jeopardy. This interplay between given systems seen in art styles - for example, Minimalist presence, Pop appropriation - was mapped on to the ways in which the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is being integrated into American social culture. Considered a victory for people with disabilities, this utopian urge tohelp the handicapped is now law, but actual implementation is hardly sufficient. Like Modernism's hopes, the social good of the ADA has been translated into strict codes, which are reinforced to maintain the law rather than really to help the handicapped. Lapthisophon references the services there are - readers for the blind, wheelchair bus lifts - only to reveal their limitations. The installation's title is taken from the ADA itself, which demands that the disabled should be served 'With Reasonable Accommodation'.

This stuttering, sputtering, earnest-but-still-ironic work is post-politically correct, and ripe for consideration in Disability Studies (a course now entering the academy). It is akin to that of Joseph Grigely, who investigates language and communication through his own experiences. But most compellingly, 'With Reasonable Accommodation' was a complicated space where blindness and sight could simultaneously occupy body and mind.