‘The Brutalist’: A Phenomenon, Not a Monolith

Far from cold or concrete, this celebrated film pulses with raw emotion, fuelled by the passions and worldview of its creators

Far from cold or concrete, this celebrated film pulses with raw emotion, fuelled by the passions and worldview of its creators

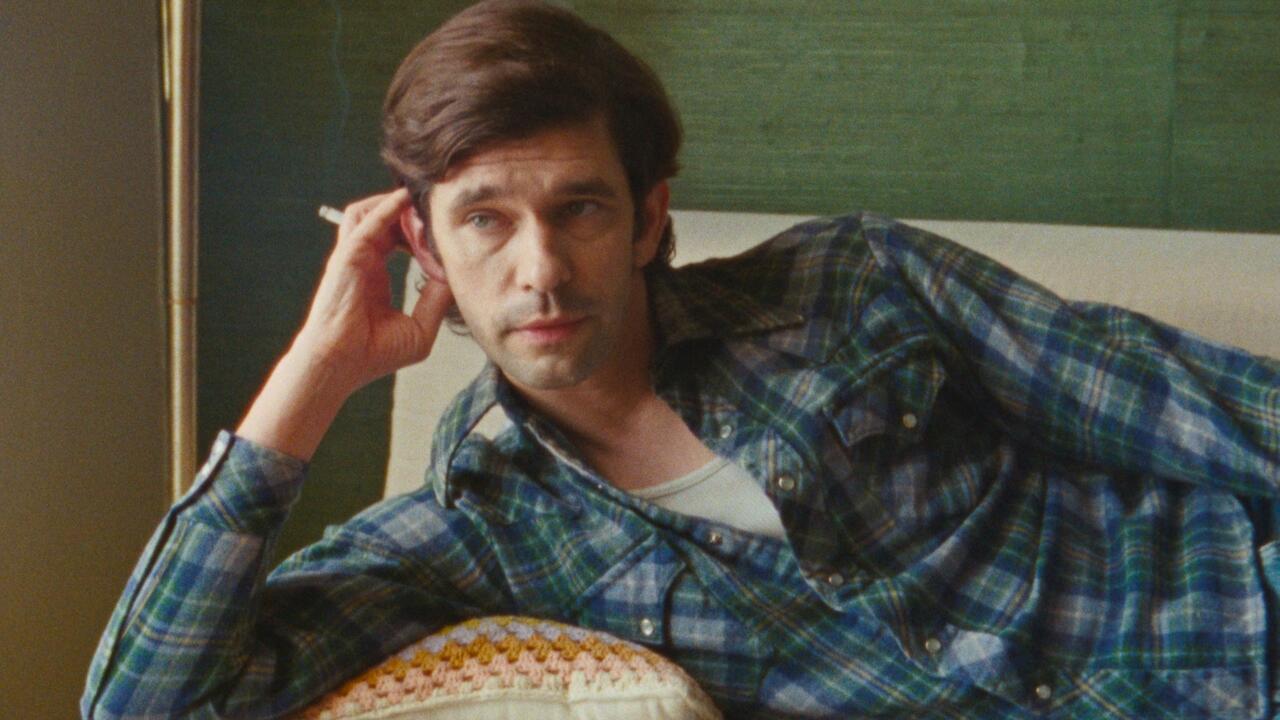

The Brutalist (2024) is director Brady Corbet’s most personal, political and impactful work. Despite only entering general release in the US and UK this week, it is already a phenomenon: its seven-year production period, relatively minimal US$8 million budget, 70 mm film reels, and three-and-a-half-hour running time have become as much a part of its mythos as the struggles of its crumpled hero, László Tóth (Adrian Brody).

The story follows Tóth – a gifted Jewish Hungarian architect who, having survived the horrors of Buchenwald, relocates to Pennsylvania after the war – as he assimilates into a waspy enclave at the heart of the American steel industry. Taking a job at a furniture store owned by his cousin Atilla (Alessandro Nivola), Tóth creates Bauhaus-inspired designs that prove too foreign for the local clientele. A fateful meeting with the industrialist Harrison Lee van Buren (Guy Pearce) initially ends badly, but both men are quickly hurtled towards their shared, uncertain future. Tóth accepts a commission to build a grand community arts centre overlooking the town, but his uncompromising vision soon grates against the cold realities of commerce. After a dizzying rise, the film grows in complexity in the second half with the introduction of Tóth’s wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), and their niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), with Corbet weaving a tale of creative partnership and dogged love into Tóth’s fading American dream.

The Brutalist is not as monolithic as all that would lead you to believe. Incorporating expertly placed newsreel footage and benefitting from the driving sweep of Daniel Blumberg’s phenomenal score, Corbet expresses great strides of American progress while keeping his film’s emotional focus as intimate as the blood in his veins. As the film nears its intermission, Tóth asks Van Buren, ‘Is there a better description of a cube than that of its construction?’ It’s a telling question that speaks to how Corbet has precisely orchestrated the film to reflect the architectural ambitions of its protagonist.

I found myself less bowled over by the film’s big swings than by its quieter moments

Reviewing the film for Empire, Jamie Graham was one of many to compare it to Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007). I see in Tóth little of the greed that marked Anderson’s protagonist, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis), and even less of his cruelty. Filmed on 35mm by Corbet’s longtime cinematographer, Lol Crawley, The Brutalist’s dazzling, much-touted opening shot ends on an inverted image of the Statue of Liberty, hanging like the Sword of Damocles. Yet, despite this ominous introduction, it’s not a film that wallows in solemnity, nor does Corbet deny his characters moments of triumph and joy.

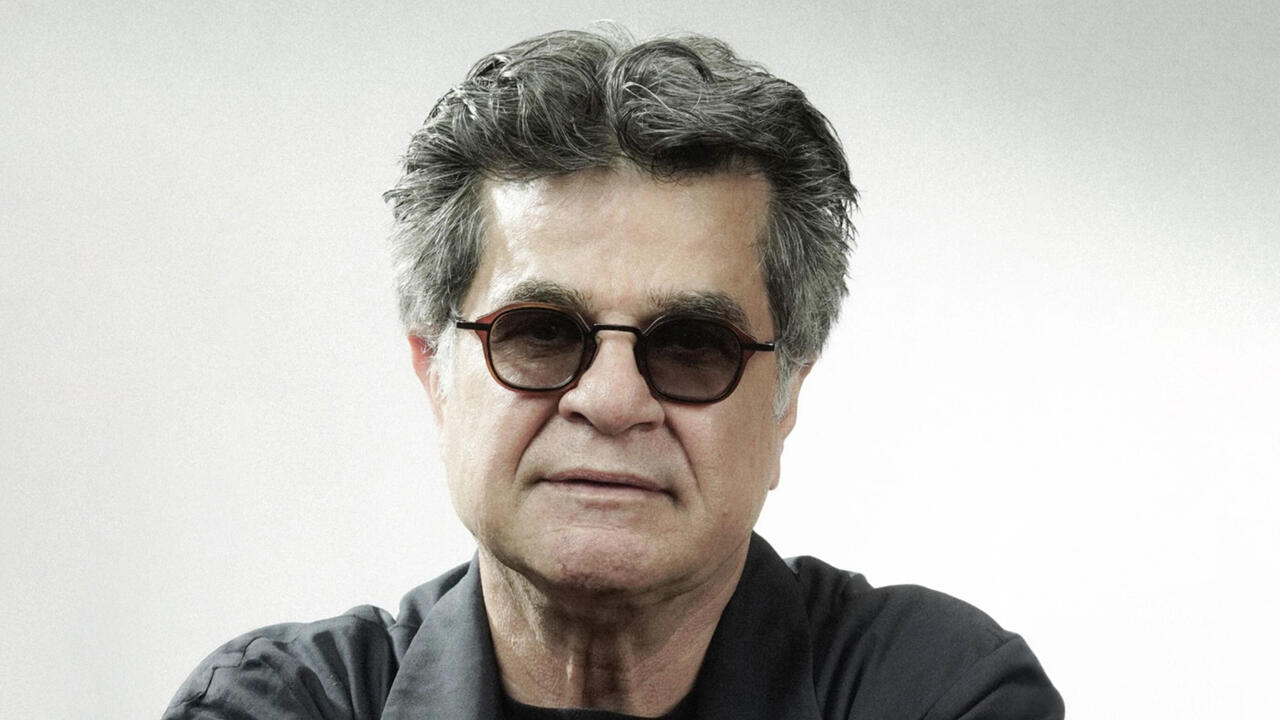

More than two decades since his breakout acting role in Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen (2003), Corbet is now a strong contender for the Best Director gong at the upcoming Academy Awards. In the early 2000s, he became known as the go-to clean-cut American for European provocateurs, including Michael Haneke (Funny Games, 2007) and Lars von Trier (Melancholia, 2011). Those filmmakers’ more puerile and playful tendencies clearly informed his first two directorial features, The Childhood of a Leader (2015) and Vox Lux (2018). Both films are brazen explorations of the relationship between fame, infamy and violence, a subject he returns to in The Brutalist, which completes a trilogy of fictional biopics.

Corbet’s partner, Mona Fastvold, co-wrote all three films, and it’s hard not to read something of their working relationship in Tóth and Erzsébet’s on-screen dynamic. At the recent Golden Globes, The Brutalist won in the categories of Best Motion Picture and Best Director. Reading endearingly from notes on his phone, Corbet concluded his speech with a dedication to Fastvold, and their daughter, Ava, who was shown crying tears of pride in the audience.

Award ceremonies do have a way of changing the general mood around a film. After receiving the Silver Lion for Best Direction at the 2024 Venice Film Festival, The Brutalist recently received criticism, including a negative review in The New Yorker, where writer Richard Brody raised issues about its positioning of Israel. As it enters the business end of awards season, however, Corbet’s film already seems to have weathered this and several other storms. Watching it for a second time recently, I found myself less bowled over by the film’s big swings than by its quieter moments: the way Blumberg’s score calms to a gorgeous, tinkling piano whenever loved ones reunite, for instance, or the delicacy with which the quarry master cleans the marble in Carrara, whispering to it like a sacred object. The Brutalist is neither cold nor concrete. It is a deeply felt film rich in its creators’ passions and worldview.

Main image: Brady Corbet, The Brutalist, 2024, production still. Courtesy: Universal Pictures UK