Catherine Opie

Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Catherine Opie greets visitors to her show at Thomas Dane Gallery. Gazing beyond the gallery window, she faces Duke Street, blue and black tattoos spilling from a grey striped t-shirt, decorating her forearms. Her knuckles catch the light, anchoring the work. Cathy (London) (all works 2017 unless otherwise stated) is calmer in tone than the artist’s seminal triptych of self-portraits depicting, respectively, a longed-for domestic idyll of a house and two women etched into hers back (Self Portrait/Cutting, 1993); Opie wearing a leather fetish hood, needles in her arms and ‘pervert’ bloodily inscribed on her chest (Self Portrait/Pervert, 1994); and Opie suckling her infant son Oliver, posed Madonna-and-Child-like, the scars of ‘Pervert’ still visible (Self Portrait/Nursing, 2004). Initially shocking, Cutting today is owned by the Guggenheim Museum's collection.

Spanning nearly 30 years, Opie’s career in fine art photography has been governed by explorations into communal, sexual and cultural identities. In 1991, her first solo show ‘Being and Having’ (a play on the patriarchal theories of Jacques Lacan) drew on her involvement in the San Franciscan lesbian S&M community. Placed before a yellow background, her friends wore moustaches, parodying gender stereotypes in cropped close-ups. For Opie’s Portraits series (1993–97) dominatrices, cross-dressers and drag kings were photographed against monochromatic backgrounds, referencing August Sander’s 'People of the 20th Century' project and the dignified tropes of European old master portraiture. (Opie has previously called images of her friends in the S&M community as her ‘royal family’.)

‘Portraits and Landscapes’, her current exhibition at Thomas Dane, while less political is no less attenuated in emotional substance. Made largely in 2017 in a rented London studio, the portraits pay homage towards artistic individuals whom Opie – a believer in tribes – holds in high regard. Using inky black backgrounds, these portraits acknowledge a mutuality between photographer and sitter – people who themselves ‘observe’ professionally. From David Hockney to Gillian Wearing, Rick Owens to Lynette Yiadom-Boayke, the works are titled with first names only. The effect is democratizing, eschewing celebrity status for individuals with fallibilities and frailties. In David, the fine piling in Hockney’s cashmere sweater speaks to the impeccably described fur collar in Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait of Sir Thomas Moore (1527). Within this dignified artistic lineage space is also made for Hockney’s personal narrative; age spots dust his cheeks, at his ear a hearing aid curves, while in his front pocket a wallet bulges, and a fleck of paint daubs his trousers. Generous and compassionate, of its time and timeless, the work bears witness to the aging body and gifted creative power.

Literature is significant to the way Opie thinks. Having been commissioned – and rejected – as a New York Times Magazine cover, her portrait of Jonathan Franzen (Jonathan, 2012) shows the author with his back to the camera, a copy of Leo Tostoy's War and Peace (1867) open midway in his hands. Light tones glisten in an arc amidst velvety darkness – from Franzen’s silver filaments of hair, to the threads in his jacket to the bone-white pages. More is revealed in the lighting of the book than in Franzen himself, alluding to his gifts in ‘lighting’ characters in his fiction. Dusty fingerprints on the pages of the book point to a history of use.

Opie understands that once something takes on iconic status, it risks being obscured by its own romance and mythology. The show includes a single landscape, Untitled #15, which presents an out-of-focus image of the white cliffs of Dover. Deliberately blurring the UK’s iconic geography, Opie invites us to re-engage with the cliffs and reverse their invisibility. The spectral image offers another form of light and shade in a room of charged, chiaroscuro-rich portraits.

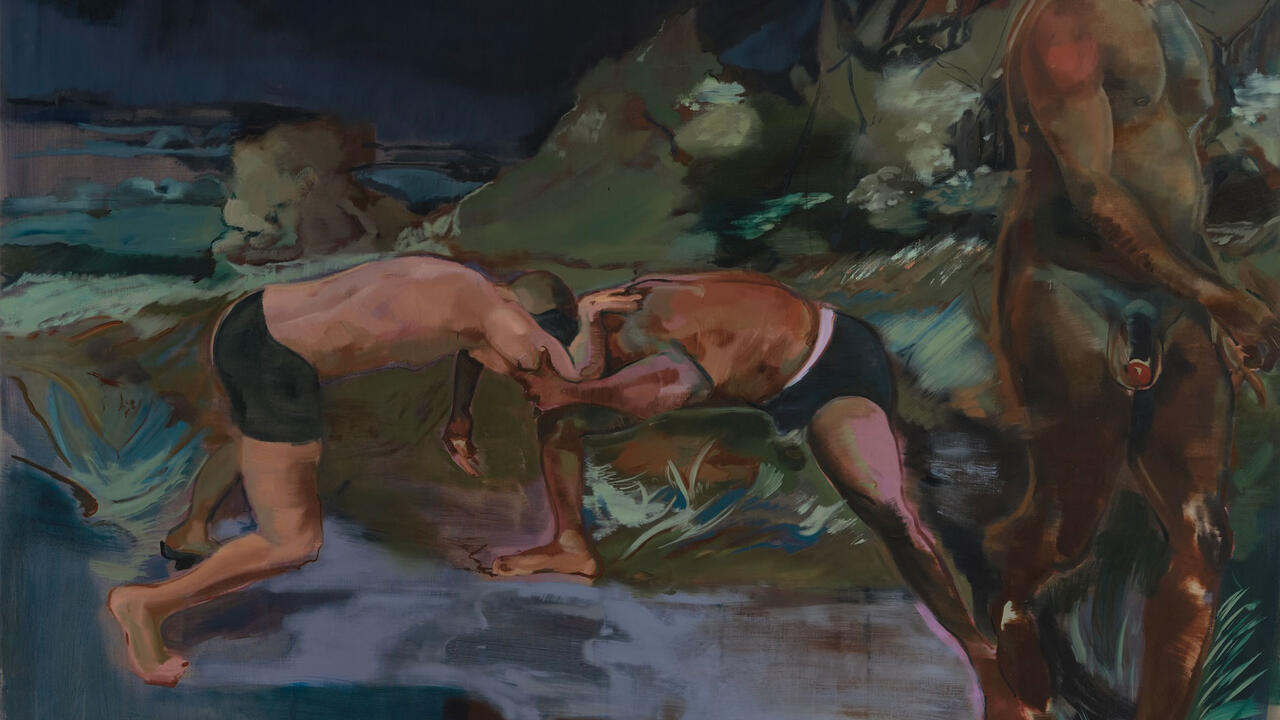

Main image: Catherine Opie, Cathy, 2017, (detail). Courtesy: Regen Projects, Los Angeles, USA and Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK © the artist