Class Languages

‘Klassensprachen’ engaged artists, writers and publishers in soul-searching around the interlinking of class, language and political change

‘Klassensprachen’ engaged artists, writers and publishers in soul-searching around the interlinking of class, language and political change

‘Klassensprachen’, or ‘Class languages’, is a multiplatform initiative comprising a two-month long exhibition, a two-day series of debates and a magazine, which will be published at the end of September 2017. An independent and collaborative effort among five German curators, its opening events took place 20-22 July at District, a non-profit space in Berlin, and brought together artists, writers and publishers to discuss the interlinking of class and language, via this productive but never clearly defined term.

The title of the project was inspired by the work of the linguist Valentin Voloshinov, who in the 1920s pushed for a Marxist understanding of language, arguing that the ‘struggle for meaning’ is inseparable from class struggle. Alongside a quote from Voloshinov, the press materials observed that in dictionary entries, initials represent terms after their first mention and as a result ‘Class, class struggle, class contradiction, as well as crisis, catastrophe and colonialism turn into C.’

The idea of a capital ‘C’ (or ‘K’ in German) as a stand in for established orthodoxies was a generative one for the first speaker, the writer and poet Juliana Spahr. She read a text which traced the influence of private foundations on the establishment of what she called ‘Capital L’ or ‘C’ literature – a class of literature in the US that is created through the selective handing out of awards, residencies and grants. Her response to ‘C’ literature was the creation of a spreadsheet which included the names of every person in the US who received a prize of over USD$10,000 from a private foundation since 1917. Watching her piece unfold, it wasn’t a shock to discover that it is usually necessary to have a college degree to create ‘C’ literature (only 200 people of 4925 did not), nor that more than half of degrees earned by these writers were awarded by 20 colleges, nor that even outside of these select colleges only 6% of students came from the poorest quartile of family income, but it was still a depressing revelation. As Spahr dryly observed, ‘all sorts of humans have arranged words since words first got arranged, it seems that there is nothing to suggest that a certain socio-economic status makes one a better arranger of words.’

Like Spahr, the translator, writer and poet Monika Rinck created a new piece in response to her invitation. It’s one that I found less accessible, partly due to its stream of consciousness format, but also because of its speedy delivery that frequently switched between English and German. However, through the subsequent discussion between Rinck and Spahr, hosted by two of the project’s curators, I understood the text to be a result of Rinck’s desire to ‘have the courage to publish more occasional poems on several occasions’ even at the risk of ‘publishing bad poems very quickly’. In other words, to create poetry which could be more responsive to the current political climate without it turning into journalism.

Moving away from the expectations of professionalism to grasp at something more spontaneous and informal emerged as a common thread throughout the programme. The curators of ‘Klassensprachen’, all of whom are either employed at well-respected art institutions or universities – including mumok in Vienna and the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich – kept returning to this idea, and I suspect it was also the reason they chose the lesser-known District as their venue. It was reflected in the exhibition design too, which contrary to the many well-known artists who took part (like Ryan Trecartin, Isa Genzken and Peter Wächtler), featured moveable walls more usually found in student exhibitions. Although it’s hard to say for sure, it seemed likely that this more intimate setting allowed for a freer, less guarded discussion between the participants in the ‘debates’.

As anecdotal evidence, I offer the rather startling outburst from the artist Josef Strau during the last panel, on writing as an aesthetic practice. Apparently inspired by his fellow participants Justin Lieberman and Rachel O’Reilly, Strau announced: ‘When I was younger, I thought it was always the most important thing to be a political artist and writer, but somehow when I was 40, I gave up. Now I make these silly writings and these sculptures of crocodiles’ – referring to his signature ‘letter tunnel’ (K Tunnel, 2017) piece in the exhibition – ‘but now I say something political.’ He then told the audience a story of observing (alleged) police brutality a few months ago, which he recorded on his phone and was subsequently threatened by an officer for doing so (in Germany, police like all other citizens control the rights to the distribution of their image). Strau went on to rally against his lefty art world friends that are quick to turn discussions to the shortcomings of American democracy (it’s now almost impossible to go to a talk or conference in Berlin without the talk turning to Trump) but who turn a blind eye to issues in their own country.

Throughout the weekend, ‘Klassensprachen’ never really came together for me as a conceptual framework, but as an initiative to stimulate discussion on art, language and politics more generally, through its eclectic mix of speakers and a relaxed atmosphere, it offered a fascinating insight into the soul-searching that many artists and writers are doing in response to renewed calls for art to effect political change.

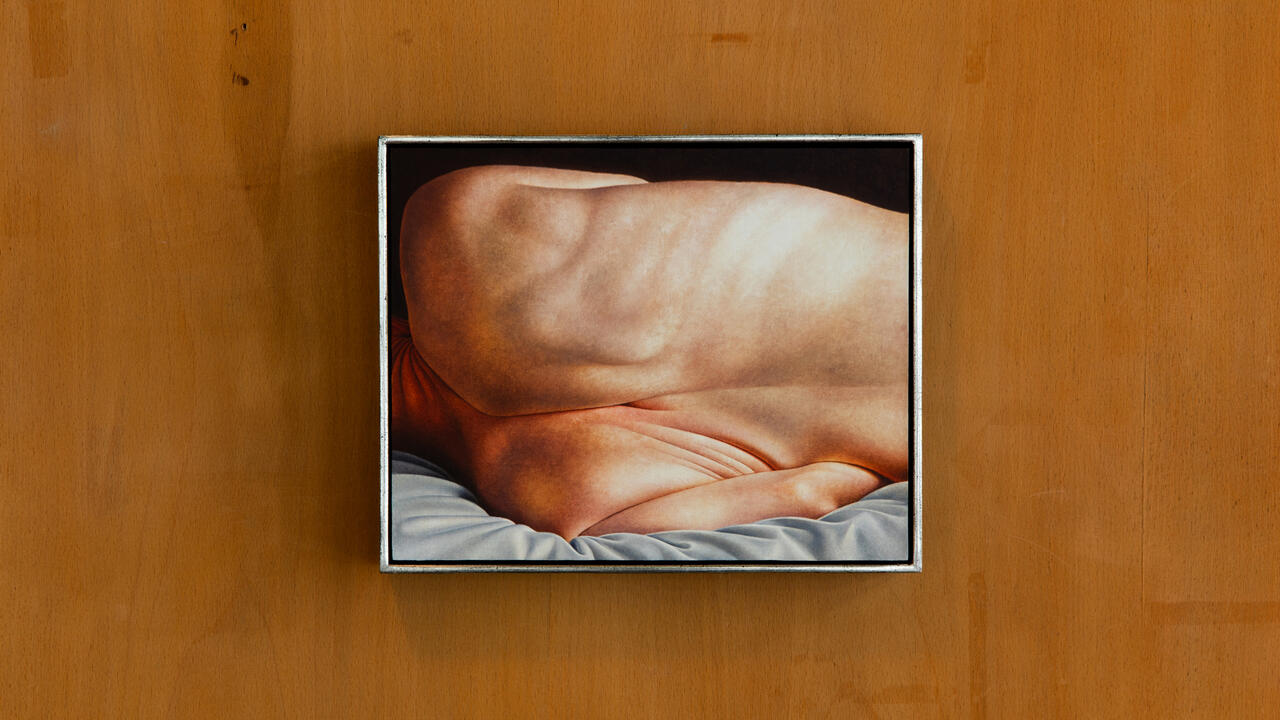

Main image: Gerry Bibby, Auto Fictions, production still, digital collage, 2017. Courtesy: the artist