Frieze Masters Podcast Series 4, Episode 2: Mark Rothko and Fra Angelico – An Encounter in Spiritual Spaces

The second episode with Christopher Rothko, Carl Strehlke and Arturo Galansino is presented in collaboration with dunhill

The second episode with Christopher Rothko, Carl Strehlke and Arturo Galansino is presented in collaboration with dunhill

When Mark Rothko visited Fra Angelico’s frescoes at the convent of San Marco in Florence, he was ‘overwhelmed,’ recounts his son, the psychologist and writer Christopher Rothko. ‘That’s what he wanted for his viewer,’ says Rothko, ‘to look at his artwork as sources of inspiration, spirituality and contemplation.’

In the second episode of the Frieze Masters Podcast 2025, Christopher Rothko is in conversation with curator and art historian Carl Strehlke and Arturo Galansino, director general of Palazzo Strozzi, to discuss the affinity between Rothko’s abstract expressionism and the Italian renaissance, ahead of a landmark show of Rothko’s work in Florence in 2026.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and the Frieze Masters Podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with dunhill.

‘Rothko in Florence’ is on view at Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, 14 March – 26 July 2026

About the Speakers

Christopher Rothko is a writer, psychologist and son of artist Mark Rothko. He has written extensively on his father’s legacy. Carl Strehlke is an art historian and curator of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. They are joined by their host Arturo Galansino, art historian, curator, director general of the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and this year’s curator of the Frieze Masters Talks programme.

About the Frieze Masters Podcast

The Frieze Masters Podcast is back for 2025, bringing you seven conversations across art history curated by Arturo Galansino (Director General of Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi in Florence).

Entitled ‘Woven Histories’ and recorded live at Frieze Masters 2025, this year’s series features artists, curators and thinkers, whose conversations weave together geographies and chronologies, and challenge us to look at history in new and unexpected ways.

Topics range from the evolving relationship between fashion and art to the role of the archive in Black history, the last Mughals and their cultural influence in India and the enduring inspiration of the old masters and renaissance art on contemporary making. Speakers include artists Tracey Emin, Glenn Brown and Antony Gormley, museum directors and curators Nicholas Cullinan, Émilie Hammen, Elizabeth Way and Carl Strehlke, and writers Edward George, Matthew Harle, Christopher Rothko and William Dalrymple.

Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and the Frieze Masters Podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with dunhill.

Transcript and Images of Works Discussed

Emanuela Tarizzo: Welcome to series 4 of the Frieze Masters Podcast.

I’m Emanuela Tarizzo, Director of Frieze Masters, and this podcast brings you our Frieze Masters Talks programme curated by Arturo Galansino under the title ‘Woven Histories’ recorded live at Frieze Masters. Featuring artists, curators, and historians these conversation weave together geographies and chronologies, and challenge us to look at history in new and unexpected ways.

In this second episode, Arturo is joined by Christopher Rothko, writer, psychologist, and son of Mark Rothko, the American pioneer of Abstract Expressionism who died in 1970. And by Renaissance scholar Carl Strehlke, co-curator of recent exhibition on Florentine Quattrocento painter Fra Angelico. Together they discover two modes of artistic expression that are more similar than they seem.

During the talk, our speakers shared images of artworks with the live audience. Please visit the Frieze website linked in the show notes below to see the images they referenced.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with Dunhill.

And now over to Arturo to introduce this week’s talk.

Arturo Galansino: The title of today’s talk is ‘An Encounter in Spiritual Spaces: Mark Rothko and Fra Angelico.’ I’m very happy to have this talk today because it really embodies my programme at Plazzo Strozzi. We just have this unprecedented and acclaimed exhibition of Fra Angelico, you know the biggest ever, full of very important discoveries, which included a restoration campaign of 28 works, 150 loans coming from 70 venues all around the world, and, uh, very important reconstructions of dismantled alter pieces, literally cut in pieces during Napoleonic time, so for the first time the public will be able to see these alter pieces again.

And then the Rothko exhibition which is coming next Spring, which is about the relationship of these great 20th century masters with Florentine Renaissance culture. Rothko didn’t like to travel very much but he liked to come to Florence, it was a special place for him. And a special place was the convent San Marco where Angelico worked, and so we will have some paintings by Rothko hang alongside the frescos by Angelico in the cells of the monks in the convent San Marco. It's never happened again, and is a kind of dialogue, and homage of Mark Rothko to this great father of the Renaissance.

Ok, let's start with, uh, with our talk. I will just ask to our guests, starting with Carl, what are the highlights of the Fra Angelico exhibition? As I said, so acclaimed, so important and why this project was so necessary.

Carl Strehlke: First of all, if I had been, as a kid, wanted to grow up to be a curator and dreamed about the greatest thing I could ever do, I probably would've dreamed about this show. So thanks to you I was able to put this together with some of our colleagues in Florence and it, it was a really wonderful experience.

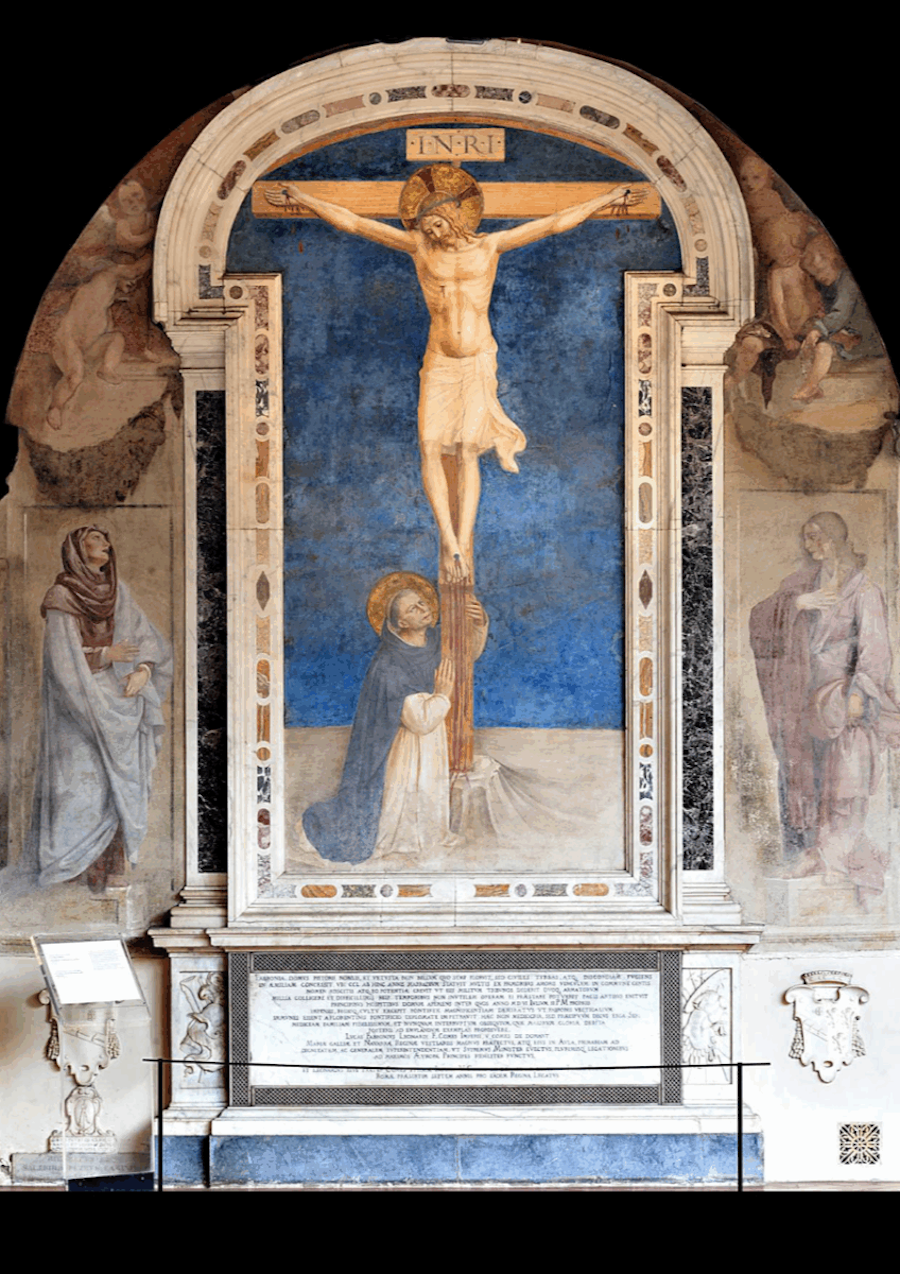

So what do we have here? We have a shot of one of the, uh, two places where the show takes place. It takes place in two areas of Florence. First, the Museo di San Marco, which is of course the Temple of Fra Angelico, where he was a friar in the convent there. And he also frescoed the cells in many other places in the convent.

And a whole other section of the exhibition takes place in the Biblioteca di San Marco upstairs off the dormitory, which was the great library, the first public library since antiquity in Europe, designed by Michelozzo and where we've brought back some of the books that were originally in the library was one of the greatest collections of humanist manuscripts.

And then there are 28 restorations, including this fresco in the cloister of San Marco, which has come back with this beautiful lapis lazuli background. And I wanted to concentrate on some of the things that we have at Palazzo Strozzi, where we have eight sections of the exhibition.

So what does the exhibition have? It has 150 objects in it by Fra Angelico, mostly, and some of his contemporaries. It comes from 70 different lenders from all around the world, largely Europe and North America. We had 28 restorations. So what we are able to do is bring some of the paintings from the Museo di San Marco to Strozzi, and it's really interesting to see people talking about them because you'll have Florentines going, “where's that painting come from?” Well, it's in the Museo di San Marco, but it's in a new context as a new lighting, and people have not noticed it before.

But one of the greatest things I think in the exhibition is a whole series of reconstructions. Alter pieces that were cut apart in around the Napoleonic period, which we have brought back and dispersed throughout museums or collections around the world, and we have brought back most of those altar pieces together, all the different parts. So here's a great, great altar piece commissioned by Cosmo De Medici around 1438 in the Church of San Marcos. It's the first Renaissance altarpiece.

There are 18 sections, 17 have been gathered together for this exhibition from nine different lenders. We've brought back the whole predella, the lower part of the altarpiece, showing stories of the two Saints, Cosmos and Damian from five different collections and other sections of the altarpiece.

And it was first of all, a great deal of study was put into this to be able to reconstruct it, digital reconstructions, which were made here in the United Kingdom under the University of Exeter, and now we have it on the wall and it's really something else.

AG: Thank you, Carl. Christopher, every exhibition on your father on Mark Rothko are global events given the importance in the art of 20th century. How will the exhibition organized in Florence next year differ from the previous ones? Okay. Less spoilers, but not too much. Okay.

CR: First of all, I have to say that while I agree with you that they are always global events, this is the first time that I can remember that we're gonna be the poor relation after seeing this Fra Angelico show, which is just extraordinary and historic, and there's no one who would've wanted to be there more than my father because he loved, as I will get to in a moment, Renaissance art and particularly the art of Florence.

But for Angelico, as we call him, the Alto Angelico, as the Italians call him, was in the firmament. So, um, incredibly, incredibly special. This exhibition is going to be in some regards, similar to other Rothko exhibitions, which is to say it's going to be chronological because, unlike Fra Angelico, who seems to be born a master, my father went through a 20 year period of being a, a figurative painter, which no matter how many times people see, a, a large retrospective, they forget about those works and they'll come up to you, say “Oh, I love those three rooms of the, uh, of the early work. I've never seen those before.” I said, “Judy, I just saw you five years ago in Washington, and there were two rooms.” And they don't remember because they have this very rectangular, my father was some sort of square. And that's what they think of.

So in some ways it will be a conventional Rothko show and that we will go chronologically through the figurative painting and surrealist painting and into the earlier transitional abstractions and finally to the Rothko that everybody knows, which will be beautifully represented with many examples both on paper and on canvas.

Uh, it will be quite a beautiful show, particularly because it's in the historic, uh, Palazzo Strozzi. So immediately we're putting him in the context of historical Florence. Now my father was a very reluctant traveller, never wanted to leave the studio, uh, only travelled to Europe three times in his life. All three of those times he went to Italy for the vast majority. Now he also ended up in England on two out of those three trips. And that's a very good thing because had he not fallen in love with England and the artists of England and the Tate Gallery and Turner, you would not have that great set of Seagram Murals at the Tate Gallery, which was a gift from him, how much he loved the English people and how much he loved the commitment to the arts here. So, but his first love was still Italy, and he spent probably between those three trips, seven or eight months, much of it in Rome. Uh, travelled through the south to Pompeii and Paestum, but he spent a lot of time in Tuscany and a lot of time in Florence.

So in 1950, his first trip, he came with my mother and he came back with my sister in my mother's womb. So, Italy’s good for lots of things, but, uh, in any case, he had been looking at Italian Renaissance art for a long time at the Metropolitan, at The Frick Collection other places in New York. He'd been reading, uh, particularly Bernard Berenson. And he was already looking at these works and trying to understand these artists, what they were trying to accomplish, and seeing, actually artists who were trying to do the same things that he was trying to do, but he sees them not necessarily iconographically doing what he's trying to do, but trying to solve the same questions of making paintings that are believable, making paintings that are immediate for the spectator, making paintings that breathe the same air that we are, and speak to the soul. Uh, so he goes, I mean, literally from sun up to sundown churches, convents, museums, back to churches, looking at every piece of art he can see in its context, and admiring the work, but more than admiring the work, trying to learn from these artists about how to solve these, these, uh, timeless questions, really.

So this is what this exhibition is different in that we will finally put Rothko in that context in the Florence that was so influential for him. We'll do it at the Plazzo Strozzi, which is again, a history lesson in and of itself, but we'll also do it back at San Marco where we're seeing Fra Angelico, but also my father came to San Marco and he came one day and looked at these frescos in these cells, and was just overwhelmed, not just with their beauty, but the idea of art that is specifically, explicitly for a spiritual purpose, and not just for the wealthy patrons, but for these monks who are every day using these as sources of contemplation. That's what he wanted for his viewer to have.

Artwork, looking at his artwork as sources of inspiration of, of spirituality, and again, for contemplation. So in five of those cells we are placing small Rothkos. I think trying to shout down Fra Angelico is a really bad idea, but hopefully works that will speak some of the same language that can have a conversation with the Fresco and hopefully the viewers will take away something from both of them. And then we'll also at the Laurentian Library put Rothko in the context of Michelangelo's, uh, dramatic stairway entrance. We'll talk about that again a little more later, but again, try to put him in direct conversation with the artists that he was looking at.

AG: Carl, the great Italian writer, Elsa Morante. She wrote in one essay that she was wondering whether Fra Angelico had been part of the Renaissance revolution. How does the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition demonstrate that Angelico was a revolutionary and in what did his revolution consist?

CS: Well, that was a good question by yourself and also Elsa Morante. She answered the question by saying actually that he was a moonwalker because she wrote that in 1969 during the time of a lot of protests in Rome, in particular student riots, and also the time that the man finally went on the moon. So she saw him as somebody going up into space, and she was very worried about the sort of religious aspect of, of Fra Angelico. I was a little uncomfortable myself talking about my little New England Purism comes out about that. But here I decide I had to confront it by showing you this, uh, wonderful picture of the figure of Christ as a king of kings, which comes from Livorno Cathedral, very rarely ever exhibited because it's on an altar in the cathedral in which you have this one-on-one quattr’occhi as we'd say in Italian, a conversation with Christ himself of a painting that's supposed to mesmerize you and make you meditate, and look at the Christ with this blood streaming down his face like that.

But what does Angelico do to communicate this and, which we have been able to do in the exhibition, I think, is to prove that even though he was a friar and even though he was a figure very committed to painting religious art, art that had a meditative aspect to it, he did it through completely Renaissance means. He, even here on this painting, you can see he was working with the fall of light, he was very interested in perspectival space. He communicated in dialogue with the major artists of his time, like Masaccio or Berti and Donatello, Brunelleschi in particular, Michelozzo. And so we have an artist who, yes, was a friar who was committed to a religious life, but who also was a Renaissance painter. And I think of him also very much in modern terms because he painted manuscripts for choral books, and he sang from those very choral books that he was painting, in front of an altarpiece that he painted. So it's sort of like a participatory art, a performance art that he was creating. And I think Angelico, as I see people going into the exhibition, you can come to him in many different avenues of thought about the subject matter he painted, about how he painted things, about his colour, about his way particularly of narration.

His predella panels, which have been brought together for so many altar pieces in the show, show him as a great, great raconteur, a storyteller who constructs his stories in these believable spaces, but also extremely human. Pope Pius 12th, who inaugurated the show, which was the last show we had 70 years ago, which happened in The Vatican, and also the Museo di San Marco, said that the myths about Fra Angelico praying before he painted, and completely devout are probably myths, but what he did was take the divine and he made it human. And I think this humanity comes out very well in, in the exhibition.

AG: Very true.

Christopher, you mentioned, um, your father's love for Italy, for our heritage, and especially for Florence. Could you tell us more about this relationship? Where are the places and the artists that, uh, of this tradition, Renaissance tradition, that your father loved?

CR: We could be here for an hour if I listed all the places that he went and that they were really like pilgrimages for him. But it starts in Rome, which he loves, in part because it's a little bit like New York. It's just crazy and bubbling and full of life all the time. But it also is so steeped in history. And he walked, not just through all the churches, again, having this conversation with the great Italian masters of painting in Fresco, but also through the ancient Roman history. And seeing this architectonic pieces, you know, the buildings that literally come up from the hillsides and these stones that still formed portions of modern Rome.

So, strictly during the years that he was so preoccupied with the myth as a subject matter, because again, it spoke to humans across cultures. These myth reoccur all these different cultures, but also to that sort of longstanding basic core humanity that, uh, he was reading Nietzsche at the time, the Birth of Tragedy, these tragic themes that run throughout our lives, run across cultures, and here he saw it in the landscape in Rome. So that is his starting point, and he goes to Rome on every one of these trips, but there were other very important destinations for him. Pompeii, seeing those roots, but also seeing, uh, The Villa of Mysteries, uh, and that deep saturated red there, he makes very clear informs a lot of his painting, from the late fifties on. The sensuality and also, uh, he so responds to Fresco because it's the idea that it’s joined to the wall, it's part of the architecture. Uh, there is this kind of relationship between what we're standing and move through and what has been presented to us from the artists.

And that's something, uh, that he takes into the sixties with him when he's largely working on public commissions, as something that travels with him through time and, and a lesson that he learned, and particularly in Florence, because, in San Marco, but in so many of the great churches, the frescoes that, you know, were done in many cases at the time or in conversations with the architects who design the churches, and the idea that you create a sacred space, and that’s something you don't just look at, it’s something that you feel.

I know that Assisi was very important for him, another spot. He also went ironically to a non -Roman site, but to the Paestum which is actually a Greek site, but on the, uh, the coast not far from Pompeii, and spent, uh, a couple of days there and realized how directly influential on his own painting these architectural, these spiritual sites, places that were made not just for looking at, but for existing in, how much that influenced his own painting.

Again, people think of my father strictly as an abstract painter, and here's the irony, once he's painting rectangles he aptly says he's not an abstract painter, he is painting real objects, part of everyday life. When he's painting these, uh, figurative paintings in the 1920s and thirties, he's already talking about himself as an abstractionist. So, it's not just that he's a contrarian, but that he wants to, not necessarily capture the specifics of the scene, but to capture something that speaks to us as human beings, a human feeling. Uh, and that's a more abstract concept than depicting something.

But we can see in these examples that he's very much looking to European examples. So, we have basically a constructed triptych of small Rothko panels. The left one is an odalisque, his own version. This painting is all of about, uh, oh, maybe 12 inches tall on a gessoed panel. So he is going back to a historical method, making that one, the one in the center, which depicts two women at what I imagine is a window in Venice. At this point, he has not been to Venice, it's probably somewhere on the lower East side of Manhattan, but it could be Venice. And again, this is a small, small gessoed panel. And the one on the right, it's as if he’s recreating the Vera painting. This is known as the Portrait of Mary. And, uh, the reproduction really does not do it justice. That blue dress is just so sensual. It's like out of a Fra Angelico painting, that sort of lapis lazuli kind of colour, and you just feel so much the texture both in her coat and her dress. It's as much about the feel as it is about the colour.

And he's, even though he's not been to Europe yet, I mean, he was born in Latvia, but he hasn't been there as an adult. He's looking at these European examples and learning from the masters, and trying to capture something that is not just a visual experience. It's, it’s a full body experience in how you interact with the painting.

AG: And do you think that this figurative production of your father should be better known?

CR: Absolutely. I rarely do exhibitions or even cooperate with exhibitions that are not showing all aspects of the work. Uh, it's not that I don't think that with his quote unquote “mature language” that he didn't discover ultimately, a more powerful means, a more direct means of trying to express these basic human emotions, trying to have this full body experience. But he's already after the same thing here. And these paintings are quite beautiful in their own right, but they also, if you look at them a little while, they're, they're doing very much what his later paintings are doing. He just hasn't, I think realized the importance of scale yet, and that sometimes the details that he's so careful with in these paintings, ultimately could interfere with this bigger message, this more philosophical, this more spiritual message, the conversation that he's ultimately interested in having with the viewer.

AG: Let me say, for me was a, a real discovery when I saw this big section you had last year in Paris was a very strong experience and uh, I look forward to displaying many of them, uh, at the beginning of the show in Florence.

Let's stay with you, Christopher. So you mentioned the figurative sources of your father. Now I would like that, uh, you tell us something about the relationship with your father, with the space. Can you tell us something in particular about the spiritual space and your father's relationship with sacred architecture?

CR: Yes, and it's ironic because he himself was pretty close to an atheist, but deeply spiritual despite that. And it was definitely a, a means of communication for him, this, the spiritual. And the last decade of his life, really a little more than a decade, is, is largely occupied by three large mural commissions. The, quote, unquote “Seagram” paintings, which ironically, painted for the spiritual space, uh, known as the Four Seasons Restaurant in, uh, New York. But this is why he ultimately withdraws from that commission because he had created, and I think perhaps with a little help from the people who commissioned him, that being largely Philip Johnson, the architect. He had created an idea about where this was going to be installed. When he finally went and ate there, he realized that he had painted for, as he realizes, a Greek temple, not, not for the Four Seasons restaurant.

So he withdraws from that commission, but in the process of making 33 paintings for a five-painting commission, he realizes that he is trying to communicate on, not just a grander scale, but on a more basic, human, elemental scale. And what he's looking at for that is not just painting, but he's looking at architecture he's creating a space. So, for these paintings, they are not only large, but they're darker than what he had painted before. He realizes that the language of the spirit, and the language of installation is not about grabbing you as you walk by in a museum, or making some collector want to buy something. He needs to slow down the conversation, have something that sort of seeps into you slowly, and that's what architecture does. When we're in a space, we can feel uplifted, we can feel hunched over by the scale or the solemnity of the space. It's not something we're even conscious of. Well, he wants to work on that pre-conscious level.

So, as I'd mentioned, he'd spent a lot of time in 1950 going into churches, and sacred spaces, and ancient sites. And it's something that continues to resonate through his paintings. So he reiterates for his Harvard Commission, which is less well known, figuratively some of that Seagram commission. So this is just a very simple white, gated rectangle on a burgundy background. This is actually a study that will be in the, uh, Palazzo Strozzi uh, exhibition. But, uh, you can see it's simple, but it's also very rugged. These are like the ancient pillars of a temple. These are something he would've seen in Rome. This would be something he had seen at Paestum, and that sort of solidity, but also that invitation of something to walk into, walk through into a different sort of space. That's the sort of feeling that he is after for, again, much of his career.

And this will actually finish the commission he gets in 1964 to create what is now known as the Rothko Chapel, which he spent three years of his life on, and actually paints the paintings relatively quickly. But he takes a studio space that, uh, he can mock up three walls of those murals on the walls because he's not making paintings, it's the only time in his career that he actually does not paint every aspect of the painting, he has assistants, execute some of these extremely large panels. But he's creating a place, he's creating a space. And this is again, um, something that had resonated with him for all his travels through Italy. Walking into spaces, and yes, there's great artwork hidden in one of the side chapels, but the great artwork is just also being in that space.

Each one of those little doorways is an entrance into a small cell, and he loved the human scale of it. He loved that you walk into this little cell and there's a beautiful Fra Angelico fresco there, and he was really moved by it. He allowed a morning to spend in there and he came back the next day. He couldn't get it out of his mind. Again, the sense of the simplicity, and just also nothing to interfere with you and that sacred experience of the art. And that's what he was always trying to communicate from, from really that moment forward.

AG: Carl, can you tell us something about, you know, the metaphysical power of this space that Angelica was really involved, and he also invented one of the very first, I will say site specific installation, no, the Madonna delle Ombre, The Virgin of the Shadow. Can you tell us about this?

CS: Well, it's interesting, first of all, hearing Christopher talk, because he was talking about how your father worked and how his mindset and how he thought, and it made me think, well, I could maybe describe Angelico doing exactly the same sort of things, and thinking out artistic problems, and spatial problems in much the same way.

And of course, here the dormitories of San Marco, which is on the first floor, when you see, you go upstairs on the upper level there. And people come into this space and you might be chatting as you go up the stairs or something, and it's very funny, all of a sudden everyone goes quiet for a second, even the school children, because you're immediately, you're not even sure where you are exactly. It's this space in which you have all these rafters, which are the 15th century ceiling of this space. And then these cells as you go by, and it's almost very mysterious. It's like those Christmas calendars you have to open up one after the other, and you're not sure what you're going to find.

And so each cell has this immediate impact. The people who look at them as you go in and you can just go in a certain way, and you begin to wonder about who lived there. Actually, everyone's asked me, first thing they ask is, “oh, where's the bed?” or “where was the desk?” or “where was the seat?” And because they want to know how they experienced that painting.

One of the things that's interesting about this, about seven times a day, all the friars had to leave their cells or leave their workspaces wherever they were, and go down to the church to go to liturgical services, at choral services, which they sang in Latin, the, uh, Psalms.

And so you would go by, you'd line up as you're going past these, uh, cells. It'd be like a flip book. You'd see a little bit of each image in each cell, and you sort of go across the whole, uh, gospel story of, of Christ or something. Each frier had their very private relationship with their painting, but then you had this very communal thing in which you're going by and looking at them every day.

And some of the paintings in the corridors, which are also done by Fra Angelico, they have inscriptions, say, “please bow your head as you go by”, or you look at The Madonna of the Shadows, which is related to a window at the end of the corridor. And so all the shadows are as if they're the shadows being cast from the window itself, or more frequently you'd see at night with an oil lamp or a candle.

Already today when you go up there, it's this very magical experience with Fra Angelico and, uh, this space, and it's hard to get out of the mind. And frequently, like Mark Rothko did, people go back the next day, I find.

CR: Just throw in, speaking of the modern, uh, you know, when we think about late 20th and early 21st century buildings, we often think about buildings where all the bones and structure are exposed. Well, look at this, uh, a few years earlier than the 20th century, and we're just, no attempt to hide it, it's just there. It's part of the space.

CS: Yeah, also because you think of the Michelozzo, or Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, this very public complete architecture and it's actually amazing. This is, dates from 1438, and you're in this kind of domestic architecture, con, conventional architecture with this exposed building. Everything is all the structures right there in front of you.

AG: Let's stay with you, Carl, for this last question. Uh, you know, you've wrote an article for the Frieze magazine about the, you know, the, the importance of Angelico imagery on modern artists from 19th and 20, and 20th century.

Could you tell us more about that? And in your view, what defines Angelico's modernity?

CS: Well, Angelico became a popular artist, it might say, in the 19th century with the Nazarenes, Queen Victoria bought painting by Fra Angelico. Ruskin adored Fra Angelico. But then it's really the French and among the foreign visitors, the Museo di San Marco, even still today, the French are the most numerous. And I think partially responsible for that is artists like Manet and Dega who both went to, who first of all had seen Angelico at the Louvre, because it's the great Coronation of the Virgin at the Louvre, brought to there during the Napoleonic era. Never returned to Italy, and still one of the great masterpieces there in Paris.

But then we know that they drew in the cells and other frescos in the convent. So you see Manet creating a print after Fra Angelico, which is a very incredible thing to do around 1863, or so. And then we have just many, many artists going to the space, going to look at Fra Angelico’s paintings. One of the more interesting I'd say is Bob Thompson, who is a black American artist from Chicago. Who got a grant from the Ford Foundation to go travel in Europe and he wanted to see and study the old masters.

And the two ones that he liked the best were Fra Angelico, and the other great master was tracks. Many of contemporary artists was Piero Della Francesca, obviously. And this is the one in which he kind of does an interpretation of the Strozzi altarpiece, which is by Fra Angelico, which is the first work in our exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi. And he really absorbed, I would say, the whole colour gamut of Fra Angelico’s palette, and created a palette of his own. Very bright colours.

We have an interpretation in a gallery here in London by Richard Hamilton, a naked woman on a telephone with a window on the side, which is really his interpretation of the great fresco of the Annunciation, which is in those corridors that we were just looking at.

And I like this particular photograph of this painting by Angelico because you see a part of the painted architecture frequently, which is cropped out of the photographs. And what I think really attracted Richard Hamilton was looking at this as the architectural space, and he creates this photographic print right there, and likes to show all parts of the architecture that we were seeing before, like the air shaft, and the light and everything else. And I think he's relating to that in doing something in place and working with this perspective from an angle.

And we have the director of the Fitzwilliam Museum here, but I didn't know he was coming when we put this in, and they did recently, the Fitzwilliam Museum, a, a small installation of a painting by David Hockney, which is actually a copy of the Fra Angelico fresco, the Annunciation. It's now on display in Florence at the Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella.

But the Fitzwilliam has one of Angelico's greatest drawings, which was acquired by the Fitzwilliam couple of years ago, which shows that same painting I showed before, the Deposition of Christ, from the Cross. And there is David Hockney, just grooving on that drawing. And I think, um, I think artists just like Fra Angelico. I mean, that's the best thing to say about it rather than trying to get too spiritual or, or too, uh, site specific about it. But it's something that artists and also the public enjoys. And seeing that in the first two weeks of the exhibition, um, people are spending a lot of time just looking.

AG: Thank you, Carl. Thank you Carl. And what are your expectation, uh, Christopher for, uh, next year's show?

CR: This is something I've tried to do for almost 15 years now, and to have my father's work in direct conversation with the city and the artists that inspired so much of it is incredibly meaningful to me, mostly because I know how meaningful it would've been to him. But I think people who come to see it, they will not be able to help themselves, they'll be incredibly moved by the experience of seeing it in Palazzo Strozzi, seeing Rothkos in the context of San Marco and Laurenziana.

I think it's going to be, um, uh, again, my father would talk about a tactile experience. That it's something that will touch you again, not just your eyes, it's going to be a full body thing. Something that you will, well, please don't touch the paintings, but you will be touched in a way that makes you feel like you will have touched the artwork.

AG: Thank you very much. Thank you, Carl. Thank you, Christopher.

ET: Thank you for listening to the Frieze Masters Podcast. Next time, Edward George and Matthew Harle discuss black cultural memory, and the powerful role of image archives.

“Its sort of infinite potential, because of its unfinishedness, is quite evocative, has its own energy.”

“Some of these images have a life beyond their own kind of timespan, and they beg all sorts of questions that are more to do with race and social history, than they are to do with art history.”

The Frieze Master Talks programme and podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with Dunhill. The Frieze Masters podcast is a Reduced Listening production.