FRONT International Is All Climax and Scant Resolution

The second iteration of the Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art asks what art can do in an increasingly fraught political climate, but simply offers symbolic gestures

The second iteration of the Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art asks what art can do in an increasingly fraught political climate, but simply offers symbolic gestures

Fastened inconspicuously to a chain-link gate and leaning against a toppled truck is a small Sol LeWitt folded paper drawing (Untitled, 1973). Above it hangs a vivid Horace Pippin painting of an a cappella quartet (Harmonizing, 1944). Such is the fraught composition of Ahmet Öğüt’s Bakunin’s Barricade (2015–ongoing), a realization of socialist revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin’s unfulfilled 1849 proposal to barricade the Prussian forces with paintings from national museums. On view for the first time outside Europe and drawn from the collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum in Oberlin – one of the many sites of the 2022 FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art – Bakunin’s Barricade, if requested, must be loaned for use in ‘extreme economic, social, political transformative moments and movements’, according to a contract that hangs adjacent to the installation. That political artworks by Alfredo Jaar, Barbara Kruger and David Wojnarowicz are also affixed makes Öğüt’s work read as an exasperation: if art seems only theoretical against oppression, we might as well use it as a literal line of defence.

Titled ‘Oh, Gods of Dust and Rainbows’ – inspired by Langston Hughes’s poem ‘Two Somewhat Different Epigrams’ (1957) – this second iteration of the triennial features 100 artists across more than 30 locations and responds to the recent hard-right political turn in the US with the premise that art is a form of healing. A framework that repeatedly asks what art can do, however, stretches metaphors thin. And, while much of the work boldly resists oppression, the triennial as a whole is all climax and scant resolution.

In a glass-box gallery at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Firelei Baéz revives the ruins of the Sans-Souci Palace in northern Haiti (formerly the residence of King Henry Christophe, a war hero in the country’s revolution for independence in 1804) with a series of blue arches springing from the wall stencilled with raised fists, broken chains and black panthers. Titled the vast ocean of all possibilities (19°36’16.9”N 72°13’07.0”W, 41°30’32.3”N 81°36’41.7”W) (2022), the installation is akin to an unconvincing stage set – its decay too fabricated, its detritus too neat – upon which these symbols of resistance unfortunately become decorative. A similar embellishment occurs in Devan Shimoyama’s February (2018), a silk flower hoodie honouring teenage racial-violence victim Trayvon Martin, which opens the Akron Art Museum’s group presentation. Ostensibly a touching act of remembrance, ultimately the work feels superficial. The silk flowers add beauty to a culturally and often tragically loaded garment, yet make it a saccharine distraction, like a luxury good.

Positioned in the narrow space of The Sculpture Center, Abigail Deville’s The Dream Keeper (2022) is somewhat more successful. The precarity of her conglomeration of scaffolds, foil, plastic, chicken wire and salt is intensified by the looped sound of a hacking saw. Brief histories of the local area – from indigenous artefacts to salt mining to photographic documentation of African Americans in the community before the Great Migration of the early 20th century – are conveyed via film projection and photocopied essays, folded and draped across the installation.

What the triennial loses in coherence, however, it makes up for in abundance, bringing a remarkable profusion of art to the region. In addition to institutions, art can be found in neighbourhood classrooms, bars, libraries, hospitals, factories, gardens and more. The breadth suggests that FRONT is truly a public – even local – triennial, meant to be seen in parts, over time. Moreover, the pocket guide to the exhibition contains a question intended to opens up the art on view at each venue. For example: ‘How can an artwork slow down the fast pace of consumption and make us look deeper?’ Or: ‘What can storytelling teach us about care, memory, trauma and grief?’ Perhaps the answers to those questions transcend the stakes of ‘good’ or ‘bad’ art.

Arguably FRONT’s most successful component is its film and video programme, whose works more gradually unveil their interiority. Tony Cokes has installed monitors in interstitial spaces throughout town; paramount is a new collaboration with Sarah Oppenheimer at Transformer Station. SM-2N: sldrty? (2022), a suprematist fragmentation of space, encourages visitors to guide two pulley-rigged black beams on axes, moving screens and projectors to momentarily censor and focus Cokes’s notably hushed video on cultural siloing. Across the street at community jazz club Bop Stop, Martin Beck’s Last Night (2016) loops onstage in total darkness. Screened during the triennial’s opening and closing weekends, the work is a complete, perfectly framed transposition of every record played by DJ David Mancuso at a 1984 SoHo loft party: the needle hovers and swerves, the record wobbles, the label blurs. The beat could go on forever.

In a back room of the Cleveland Public Library, Moyra Davey paces throughout her film Horse Opera (2019–22) while narrating the story of Elle, a young woman who might have been at Mancuso’s party. Davey’s narration is staggered, like the rocking of her zoomed-in camera, locked with wonder on bird feeders, a dragonfly caught in a web and a flying squirrel. In a darkened study room of the Cleveland Clinic’s Samson Pavilion, Wong Kit Yi debuts Inner Voice Transplant (2022), a similarly understated video essay that is subtitled like a karaoke track. A cheap disco ball spins among generic couches as we listen to Wong link ancient medicine to her convalescing mother and the jiangshi, or Chinese hopping vampire, cursed to steal souls forever. In another repurposed room of the pavilion, Naeem Mohaiemen screens Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown, 2021), an enveloping attempt to understand how and why life ends. Near the end of the film, a husband carries out one last waltz with his wife amidst medical equipment, which we realize may have just been an unfulfilled desire.

Though ‘Two Somewhat Different Epigrams’ is only four lines long, Hughes arrived at the poem after concerted revision – his papers can be seen in an accompanying exhibition at the Cleveland Public Library. An extra preposition or a misplaced line break can be the difference between overstatement and deep feeling. Perhaps, then, it is the art-activist collective Cooking Sections whose work is most successful. Since the 1960s, due to heavy industrial pollution, nearby Lake Erie and its attendant microclimates have been steadily dying. Cooking Sections installed two fountains in the harbour to re-oxygenate the lake, but they are only poignantly symbolic – hundreds, perhaps thousands, more would be needed. At SPACES gallery, there is nothing to show for the collective’s contribution beyond a photograph and the fountains’ co-ordinates – because, perhaps, we’ve reached our limit of putting on shows of ecological or political awareness. Other works at SPACES support this ethos: Jumana Manna’s Wild Relatives (2018) is a patient, observant epic of seed dispersal while Haseeb Ahmed has brought a real-time opera of the wind and its rhythms into the gallery (Vanquish the Void, 2022). The presentation at SPACES is not about reaffirmation but, rather, a willing optimism. Over the next three years, Cooking Sections will bring local farmers together in hopes of reducing chemical fertilizer use. We can only hope that, once the work leaves the gallery, its objective will continue in the world.

FRONT International 2022 is on view at various venues across Cleveland, USA, until 2 October.

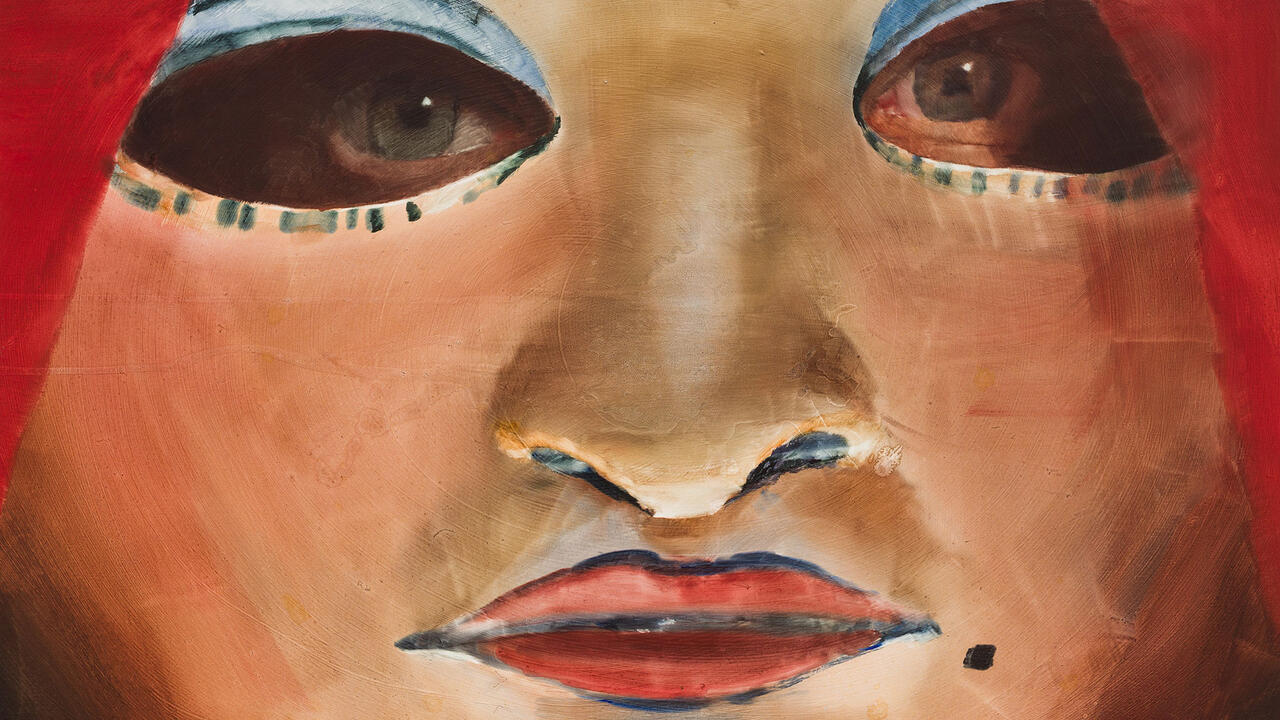

Main image: ‘Oh, Gods of Dust and Rainbows’, 2022, exhibition view, FRONT PNC Exhibition Hub at Transformer Station, Cleveland. Photograph: Field Studio