Jan De Cock

In The Production of Space (1974) Henry Lefebvre credits the Bauhaus movement with the emergence of the awareness of space: Paul Klee, while teaching at the Bauhaus in Dessau, claimed that artists do not show space but rather create it. Such a statement certainly holds true for the work of young Belgian artist Jan De Cock, whose sculpture redefines space, using intricate, modular structures made from inexpensive materials such as chip-board, plywood and naff wood-effect linoleum.

It is part of the deceptive and subtle pleasure of De Cock's work that this shoddiness of material is belied by the skilfully designed and beautifully crafted use to which it is put - which, in turn, fools the viewer into thinking its purpose is merely functional. It is only after being ingeniously guided on a path of discovery by the pieces themselves that their infinite complexity is revealed. Often the visitor can lounge or sit on his works, from where their attention might be directed to usually inconspicuous details of the building that houses it or else, within a gallery context, toward a second aspect of De Cock's work: large light-boxes that immortalize previous interventions in other locations, usually ephemeral structures in museums, galleries or institutions.

On the surface, De Cock's two-phase solo show in Cologne, entitled 'Denkmal 1a' (Monument 1a)', was simple to the point of being Minimalist: it comprised a long shelf, a small table and a low platform with fitted cushions for reclining on. But there were also various subtle clues that hinted at the work's profundity. Most of De Cock's interventions are designated as examples of a 'Denkmal', an allusion to Adolf Loos' conviction that only two types of architecture could be considered art: 'the cenotaph and the monument'. Since this is the same Loos that claimed ornamentation was criminal, the reference clearly makes a statement regarding the artist's clean and austere aesthetic leanings.

The first phase of the show involved the sculptural structure, whose shelf was neatly filled with hundreds of copies of a book (Denkmal ISBN 9080842419, 2004) that visitors could read at their leisure, accompanied by a series of small, panoramic black and white photographs (Temps Mort, Idle Time, undated) depicting architectural details and urban views, many of them of museums and similar institutions. The very modular construction of the artist's book (three volumes encased in a hard sleeve) is a reflection of De Cock's constructions, and its pages, besides documenting many of his earlier works, contain timetables, lists, indexes and illustrations that act as an encyclopaedia or operating manual of his brain. Thousands of images reveal his influences, from the more obvious - Donald Judd, Daniel Buren, Frank Lloyd Wright - to the more arcane - such as Vladimir Tatlin or Giotto.

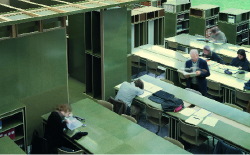

In the second phase of the show the small photographs were removed from the gallery wall and replaced with a new series of large-scale colour photographs mounted on lightboxes in a monumental documentation of a sculptural work simultaneously on show - indeed, in use - in Ghent at the Henry Van de Velde University library, which the artist had totally restructured (Denkmal 9, 2004). The library is thus not only the main subject of one of the volumes but also the context for its presentation: in the photographs the book appears on the library's shelves, as well as on the shelf in the gallery. Each of the elements - gallery, university, book, sculpture, photography - is thus connected to, and dependent on, all of the others.

In all of the interventions the resultant photographs are more than a mere process of documentation. De Cock conceives of them in a filmic way, works on them with a photographer, whom he refers to as the 'camera operator', positions the characters and choreographs a kind of performance. Each image is shot using a strict 3-second exposure that allows him to capture the movement of, for example, visitors to a museum, who are made to mimic gestures from the displayed works, creating what has been de-scribed as 'real time paintings'. The university students are seen studying, their activity as transient as the constructed works scheduled to be dismantled after the exhibition's run. Thus the lightboxes actually become a monument of sorts to these temporarily built structures. They allow the kind of glimpse that Theodor Adorno described in 1947, in Minima Moralia: 'Perspectives must be fashioned that displace and arrange the world, reveal it to be, with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear to be one day in a messianic light.'