Pity and Terror: Picasso’s Path to Guernica

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

As anniversaries go, few are more potent than the one marked by this exhibition. 80 years ago, on the afternoon of Monday 26 April 1937, aeroplanes of the German Condor Legion, acting in support of Franco’s Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War, bombed and virtually obliterated the undefended Basque town of Gernika: one of the first times Blitzkrieg was unleashed in Europe. Yet, what can possibly remain to be said about Pablo Picasso’s famous response to this atrocity: his monumental painting Guernica (1937)? Perhaps it’s just as instructive to stop and marvel at the myriad Guernicas that multiply in the gift shop as posters, jigsaws and keyrings, evidence of its transition from an anguished act of protest into a familiar symbol of peace?

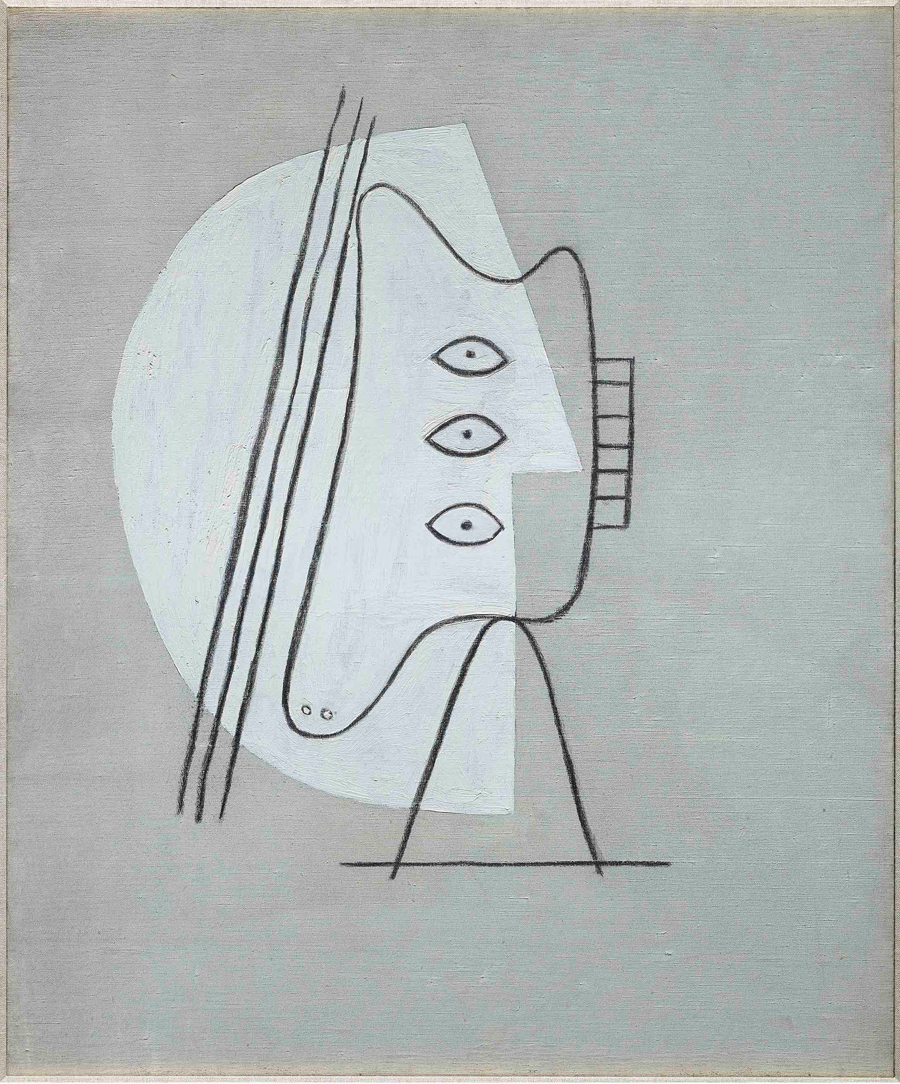

Miraculously, this exhibition, ‘Pity and Terror: Picasso’s Path to Guernica’, achieves the impossible. Curated by T.J. Clarke and Anne M. Wagner, it sets up a concise, un-crowded trail of works, each of which feels essential to its argument, delivering us in front of the painting with eyes opened and defences down. How is this done? Those who have read Clarke’s book Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica (2013) will be familiar with his impatience with what he calls ‘the horrible penumbra of gossip and hero-worship’ that so often surrounds discussions of the artist’s work. Instead, his focus – in both book and exhibition – is on identifying the artistic precedents in Picasso’s oeuvre that allowed the extraordinary figuration in Guernica. He finds it in Picasso’s problematic output between the mid-1920s and early ’30s, a period during which the artist broke out of the enclosed world-within-a-room of Cubism and created works in which the female body took on a monstrous, semi-human form.

The first route towards an escape is signalled by an open window. In Mandolin and Guitar (1924), on loan from the Guggenheim, Mediterranean light breaks in from a balcony, illuminating the room’s interior and traditional still-life elements in vivid colour. The Three Dancers (1925) from Tate – a painting which rarely travels and that Picasso himself considered more important than Guernica – unleashes its violent, Bacchic frenzy even more impressively in the human scale of the Reina Sofía’s galleries. Nothing seems to have quite prepared Clarke for the arrival of such works and he still seemed stunned during the press view, speaking admiringly of Rosario Peiró, Head of Collections at the Reina Sofía, and her ‘bulldog’ determination to make his dreams come true. He stood admiring three works: Woman in an Armchair (1927) and Figure and Profile (1928), which flank the larger Painter and his Model (1928), their distorted figures contained within geometric zones of red, white, yellow and blue. ‘They’re nods to 1920s abstract painting’, he suggested, laughing. ‘Take that, Mondrian’!

But it is those mercilessly portrayed female figures that strike home when placed in the context of the great painting whose 80th birthday we are celebrating. The smooth stone contours of Nude Standing by the Sea (1929); the extraordinary large chalk drawing on canvas, The Swimmer (1934), her breasts and limbs rearranged by the unfamiliar element of water as others will be by dynamite; the flesh-covered copulating insects of Figures by the Sea (1931), their darting, dagger tongues reappearing in the mouths of the wounded horse and wailing women of Guernica and in the attendant studies and afterthoughts that together make up a gesamtwerk, a total work of art. What the reports of war in Spain grant Picasso, the pitiless observer, is compassion. The effects of bombardment are recorded in the bodies of animals and babies; women’s bodies become weaponized, with projectile tears and bombs for breasts. In 1937, Guernica sounded a warning of what was to come. Set within this stunning exhibition, against a backdrop of news from Syria and Mosul, its prophetic power burns on undiminished.

Main image: ‘Pity and Terror: Picasso’s Path to Guernica’, 2017, installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. Courtesy: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía; photograph: Joaquín Cortés / Román Lores