Variations on a Theme

Gallerist, collector, curator and director René Block talks to artist Maria Eichhorn about ambition in art, the unexplored diversity of Fluxus and the importance of music in a career spanning 50 years

Gallerist, collector, curator and director René Block talks to artist Maria Eichhorn about ambition in art, the unexplored diversity of Fluxus and the importance of music in a career spanning 50 years

Humour

MARIA EICHHORN René, ever since you set out as a gallerist and curator, you’ve been suspicious of artists who behave like stars. Instead, you feel an attachment to critical, nonconformist artists with a sense of humour. Is the reason for this that you yourself share these same characteristics?

RENÉ BLOCK There are people who radiate happiness and positive energy. Many of the artists I’ve had the good fortune to meet have been like that: John Cage, Nam June Paik, George Brecht, Henning Christiansen, Joseph Beuys, Marcel Broodthaers, Terry Fox, KP Brehmer – to name just a few who are no longer alive, with whom I can no longer laugh. These artists all have one characteristic in common: they had the strictest standards regarding the quality of their works, but for all their artistic rigour and refusal to compromise, they also had a critical distance to their works. They were able to comment on them with laughter. Any problems that arose could be solved with laughter. It was a pleasure to work with them and to plan projects together. Fortunately, this Fluxus characteristic is also to be found in many young artists who have a critical, nonconformist attitude to the system, but who still think positively.

Friendship

ME You’ve had lifelong friendships with many artists, including KP Brehmer, a close friend since you studied together in Krefeld. Like love, friendship is a central theme in philosophy. What does friendship mean to you?

RB Things like that are hard to put into words. The relationship or bond to partners, parents and children is what we call love. Relationships to other people, if they are strong, are referred to as friendship, although friendship may sometimes be closer, more intimate and more enduring than love. The death of Beuys and the death of KP Brehmer were no less painful than the death of my mother. Having friends is a privilege that cannot be overvalued. Talking about it really should be left to the philosophers, although a popular song from 1930 put it in a nut‑shell long ago: ‘A friend, a good friend, that’s the best thing in the world …’

KP Brehmer

ME Works by KP Brehmer like Korrektur der Nationalfarben [Correction of the National Colours, 1972] for documenta 5 [1972] and Seele und Gefühl eines Arbeiters [Soul and Feelings of a Worker, 1978–81] were important precursors to some of today’s critical art praxis. With his ‘visual agitation’, as he called his work, he aimed ‘to infiltrate the institutions’. In spite of this, Brehmer has not become a key figure in recent art history. How do you explain his marginal position? Did he lack ambition?

RB Is ambition not one of the seven deadly sins? Yes, the kind of ambition that makes many artists so annoying early on and so ridiculous later when they start behaving like stars, he didn’t have that. Instead he was honest. Honest enough to give one of his exhibitions the title All Artists Lie [1998]. KP Brehmer can best be compared to two composers: the Frenchman Erik Satie, who worked as a postman, delivering letters every day while Stravinsky was quaffing champagne, and the American Charles Ives, who was an insurance salesman. In both cases, their musical importance was only recognized 50 years after their works had been composed. The same is happening with Brehmer, whose artistic works from the 1960s and ’70s are only now being recognized – by a few – as pioneering. He was neither painter nor sculptor but a graphic artist. He brought about a revolution in print-making techniques and channelled the resulting new content into art. He did this on the quiet, no one noticed at the time.

Fluxus

ME Beginning in the 1960s, you organized many exhibitions of Fluxus artists, supporting them and building up a large collection of their work. Although the movement’s potentially scandalous actions were popular with a wider public, Fluxus is accorded a lesser importance in art history. Why did Fluxus not attain the same status as Minimal or Conceptual art, for example?

RB The reason is simple. Fluxus was against the art market, against the system, whereas Minimal and Conceptual art were invented, and even named, by this system. Fluxus, as something fluid, something ungraspable, is only now being identified as important. With artists like Beuys, Cage and Paik openly advocating the philosophies and strategies of Fluxus, ‘serious’ critics could no longer ignore the phenomenon. But Fluxus has by no means been explored in all its diversity. There seems to be an unbridgeable gulf between the radical concept art of the early La Monte Young, George Brecht, Robert Watts or Tomas Schmit and the entertaining and amusing performances of Emmett Williams, Ben Vautier and Benjamin Patterson. Not to mention the individual positions of Beuys, Cage and Paik.

Joseph Beuys

ME Your career has been closely linked with Joseph Beuys. Not only via the famous action I Like America and America Likes Me [1974] in New York, but also through countless joint actions and exhibitions at your gallery in Berlin, at biennials, etc. Although Beuys is without a doubt one of the most important artists of the postwar period, he is often viewed critically by American art historians in particular, but also by Fluxus artists, whom you hold in high esteem. What is your position on Beuys?

RB As a 22-year-old art student opening a gallery in 1964, besides fellow student KP Brehmer, the most important figure to me was our teacher Joseph Beuys. His position gave me something to relate to. My relationships with Gerhard Richter and Wolf Vostell, who were ten years older (both born in 1932), were not insignificant either, of course. But the key influence in my later life and for my work came from Beuys, who also shared my roots – we both grew up in the Lower Rhine valley. The critical attitude of certain orthodox Fluxus artists towards Beuys was due to their strict belief in the tenets laid down by George Maciunas in his early manifestoes. Later on, incidentally, Maciunas had a good relationship with Beuys. Cage appreciated Beuys and Paik positively revered him. Those are the positions that matter to me today. The fact that certain people on both sides of the Atlantic reject or criticize Beuys and his work only serves to highlight his importance.

Lidice

ME In 1966, the British doctor and politician Sir Barnett Stross issued a worldwide call to donate artworks to Lidice. This village near Prague was razed to the ground by the Nazis in 1942, as revenge for the assassination attempt on Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich. All of the village’s men were shot; women and children sent to concentration camps. You passed on the appeal from Stross to the German artists you knew, and repeated the call in 1997, bringing together a valuable collection of German art that is now in Lidice. It includes works by Richter, Sigmar Polke, Blinky Palermo, Katharina Fritsch and Rosemarie Trockel. Stross considered the ‘Lidice Shall Live’ movement a symbol of peace and friendship among nations. Did you ever meet Stross in person? What moved you to act on his appeal?

RB I’m glad you mention this important action and demonstration in exhibition form. I never met Stross. I just heard about his appeal and passed it on to the German artists I was associated with at the time. They all contributed small or large works. The result was a 1967 exhibition with 21 artists called Hommage à Lidice, intended as a gift to the village. At the time, this was not only difficult, but, for political reasons, almost unthinkable. In 1968, we nonetheless made it as far as Prague. After the city was occupied by Warsaw Pact troops – under Russian command but with East German involvement – the works disappeared for many years, and they were not found again until 1996. In 1997, three decades after the original exhibition, I repeated the original appeal, addressing a younger generation of German artists who had not lived through the war. This added 31 works to the collection, so that our gift now consisted of 52 works. They are on show at the museum, the converted former cultural centre of the new village of Lidice. It is perhaps the nicest, and certainly the most intimate collection of contemporary German art.

Music

ME Your interest in music is reflected in the exhibition you curated at the Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1980, Für Augen und Ohren [For Eyes and Ears] – which is considered the birth of sound art – your directorship of the DAAD music programme and your countless activities and projects with composers and musicians. You once said, ‘my exhibitions ought to sound like music’, defining your curatorial practice in terms of the role of the conductor. What does music mean to you in relation to fine art?

RB My exhibitions ought to sound like music, yes – but not every critic understands music. This was certainly the case recently at Museum Essl in Vienna. The title Eine kleine Machtmusik [Macht meaning power or might] was intended, among other things, as a reference to the musical form of the hanging. The show was about art from 1960s Vienna, with outstanding works by Arnulf Rainer, Hermann Nitsch, Otto Mühl, Günter Brus, Maria Lassnig, Valie Export, Christian Ludwig Attersee and Gerhard Rühm: a report from the Essl collection, hung according to the rules of counterpoint, variations on a theme in the scherzo section, and so forth, in the classical form of four movements. The artists liked it. The critics didn’t like it at all. They were expecting something different. But really, music and art and literature and film, they can’t be separated. Either it’s good or very good, or it’s uninteresting. It’s no secret that my first inroads into the world of culture from the mid-1950s were provided by the experimental night-time radio programme on NWDR, which usually played the latest electronic music from its legendary studio in Cologne. So I was more familiar with names like Hindemith, Nono, Berio, Cage and Stockhausen than with Klee, Kandinsky, Schwitters or Duchamp. But finally, through Stockhausen, I came across Fluxus and from there I found my way to art. You want to know what music means to me in relation to fine art? Well, I could live without pictures, but not without music.

Interviews

ME Reading through your countless interviews and conversations, I was struck by the polished dialogues with Martin Glaser. They read like tête-à-têtes with yourself. Few people speak with you so knowledgeably, with such familiarity and directness. Who is Martin Glaser?

RB Interviews are a chore that I hate, but sometimes they cannot be avoided. The questions asked, and thus the answers given, usually fail to touch on the actual subject. Because the person asking the questions is following their own interests from the outset. For me, the conversations with Glaser have been an exception. In some cases, they have allowed me to think more deeply about the concerns and conception of an exhibition. Some of these conversations have been published in catalogues. Glaser lives a secluded life on the Danish island of Møn.

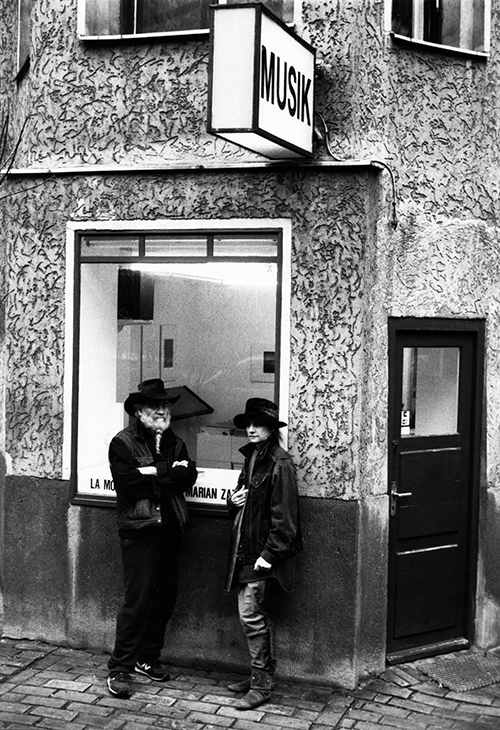

Ursula Block

ME Since 1981, Ursula Block has been running the record shop and gallery Gelbe Musik close to your former gallery on Schaperstrasse in Berlin. Musicians and artists from around the world appreciate Ursula’s expert knowledge of ‘Neue Music’ and the unparalleled range of works on sale in the gallery shop. How did the founding and naming of Gelbe Musik come about and how would you describe the interaction between your activities and Ursula’s?

RB The name was taken from the title of a Kandinsky painting. Early on, the world ‘gelbe’ [yellow] was printed in blue. The focus of the shop and gallery is on combinations of art and music, insofar as they take place on recording media such as records, cassettes or CDs. There are also small exhibitions. The music gallery has long since become an archive, a source of information. At Gelbe Musik, Ursula is still strongly pursuing much of what was set in motion 35 years ago by the Für Augen und Ohren show. Today, with Ursula’s guidance, it is my most important source of inspiration.

Cultural politics

ME As director of both art and music for the DAAD’s Artists-in-Berlin programme [1982–92], the director of the art department at ifa [Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations, 1993–1996] and artistic director of the Kunsthalle Fridericianum in Kassel [1997–2006], you have often played a pioneering role in the field of cultural politics – be it paving the way for the transnationalization of cultural exchange programmes or initiating dialogue with Turkey and the Balkan countries. In 1996, you resigned early from your job at the ifa in Stuttgart. Was one bone of contention that you purchased art by non-German artists for the ifa collection?

RB There was no open dispute on that issue, but it may have played a part. No, it was just that the personal chemistry with the then secretary general wasn’t right. Although there were several more ideas for projects to enable Germany to be presented abroad as an exemplary field of cultural experimentation, as begun with the Embodied Logos and Fluxus in Germany shows [both 1995], these would have required some positive identification from the institute’s directors and the German Foreign Ministry. The only non-material support we received came from the Goethe Institute. The invitation to organize the 4th Istanbul Biennial in 1995 made it easier for me to leave. But directing a biennial also offers an arena for engaging in cultural politics at an international level. I have always seen myself not only as a conductor, but also as an ambassador.

Feminism

ME After the many feminist struggles of the past, we are still seeing many exhibitions featuring few or no women artists, without this being publicly condemned or even criticized. In an interview I conducted with you in 1998 you said that you curate shows like Echolot [1998], that featured only women artists, for men, ‘so that all the weedy bigots wake up at last’. Are you a feminist?

RB No, that would be silly. It would mean that, because I’ve rarely exhibited works by dark-skinned artists, I would also have to be called a racist. The phrase you quote is 15 years old. People say all kinds of things in specific contexts. I’ve always tried to think of the major exhibitions I’ve been responsible for as platforms on which new issues are offered up for discussion. In recent years, these new issues have often come from women artists, especially women artists from the so-called periphery. This is a perfectly normal development. There’s no need to waste words on it.

The art trade

ME You are well acquainted with both sides of the art trade, both buying and selling, from long years of experience as a gallerist, private collector and director of the art department at the ifa. In 1967, you co-founded Art Cologne, the world’s oldest art fair. How has the art market changed in recent decades? Can art exist outside of the market, for example exclusively in discourse?

RB What we founded in 1967 was called Kölner Kunstmarkt and it was intended as an initiative by 18 German galleries. We wanted to meet once a year somewhere in Germany and pool our experience. It was about sharing information with each other and with the audience, information about contemporary art in Germany, especially more recent work. Consequently, our activities were funded by Cologne’s municipal culture office. The fair was held in public buildings, the Gürzenich, the Kunsthalle and the Kunstverein. Each gallery paid the same small fee for a booth, all the same size. The booths were allocated by drawing lots. So the early fairs were cultural events. The growing commercial character of the fair and the interest from international galleries were neither planned nor expected. Good ideas get copied. Be it museums at night, biennials or art fairs. But they are also modified. Adapted to the needs of a new audience. What was local became global. Whereas in 1967, art collecting was still a quiet passion, with sales of works a matter of discretion, today the market has become very loud. Big international collectors and big international galleries, as well as auction houses, outdo each other with record prices, reaching new heights every week. This market has taken on a life of its own. Of course, the moment it is bought or sold, an art work is also a commodity. But art exists primarily outside the laws of the market. In the many non-commercial institutions, at biennials or comparable exhibitions. But at biennials in particular, art discourse takes place independently of the market. The artist is free to decide if he or she prefers to remain independent or submit to the market.

Koç Collection

ME Together with Melih Fereli and Emre Baykal, you work for the Koç Collection in Istanbul. Having opened the Arter exhibition space in 2010, Koç is now planning a private museum. Do you buy independently of one another, or is there a shared approach with regard to building a coherent collection of contemporary art?

RB Fereli, Baykal and I are building a collection of contemporary art for the Vehbi Koç Foundation in Istanbul. There are plans for a dedicated museum. Preparations are becoming concrete. What we have in mind is a coherent collection, even if each of us can purchase independently within a certain framework. Major acquisitions are agreed on unanimously. The collection focuses on the development of Turkish art in recent years. The period we are collecting, both in Turkey and abroad, begins in the 1960s. It is already having a positive influence on other private collections in the country. Turkey has no public collection of contemporary art. With their own museums, the private collectors are actually performing a public duty.

The Unanswered Question

ME Your current exhibition at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein and Tanas is called The Unanswered Question. Iskele 2, a reference to the 1908 composition of that name by Charles Ives. Ives described the work as a ‘cosmic landscape’ representing ‘the perennial question of existence’. How is the exhibition title to be understood in relation to art?

RB I understand the title the way Ives explained it: as the perennial and probably unanswerable question of existence. The question of the origin of the universe, but also of our being and actions. What’s it all for? Who’s it all for? With this latest exhibition at Tanas, I’m glad to repeat the old and similarly unanswered question of Serbian artist Rasa Todosijevic: What is art?

Today – Tomorrow

ME In 2008, in addition to your other projects, you opened a private art museum on the Danish island of Møn together with BjørNørgaard, Ursula Reuter Christiansen and Henning Christiansen, where you are responsible for programming. In 2014, the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein and the Berlinische Galerie are planning a show about your archive with the title Ich kenne kein Weekend [I know no weekend] – after a famous quotation from Beuys. How do you manage to keep an overview of all these activities and organize your life?

RB My life is chaos. My office is chaos. My thinking is chaos. But I am living.

René Block is a gallerist, collector and curator. He opened his first gallery in 1964 in Berlin-Schöneberg which ran until 1979. From 1974–7 he ran a second gallery in SoHo, New York. Block’s current gallery, Edition Block in Berlin, opened in 2008.

This conversation will be republished as Eichhorn’s contribution to The Unanswered Question. Iskele 2, curated by René Block at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein in cooperation with Tanas, Berlin (8 September – 3 November 2013).