Where Art Invents the Future: Mónica Bello Introduces Platform Dalí

A new initiative reopens Dalí’s fascination with science, asking artists to step into dialogue with the breakthroughs shaping our world

A new initiative reopens Dalí’s fascination with science, asking artists to step into dialogue with the breakthroughs shaping our world

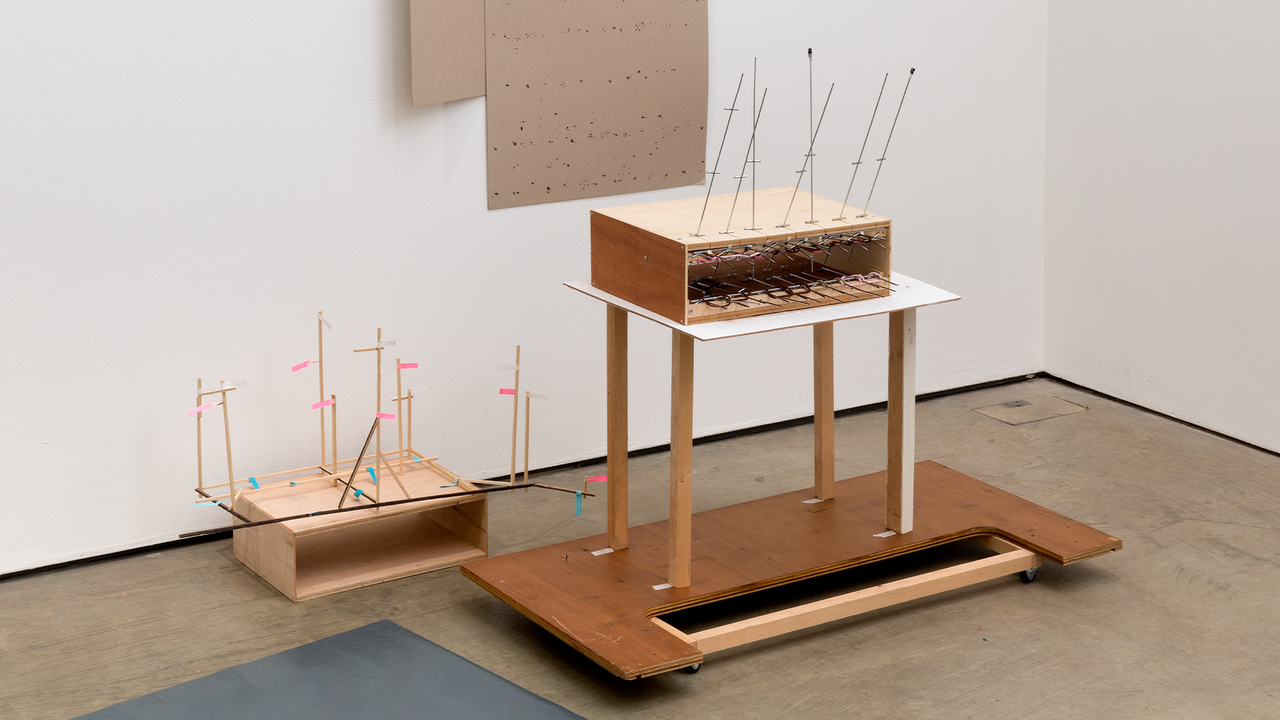

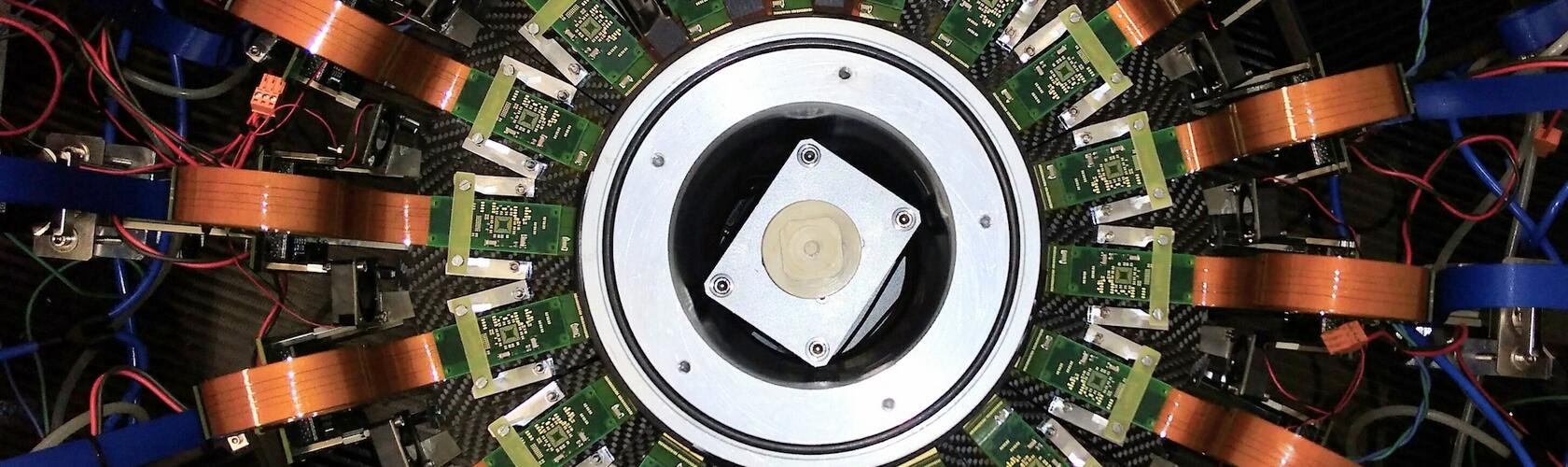

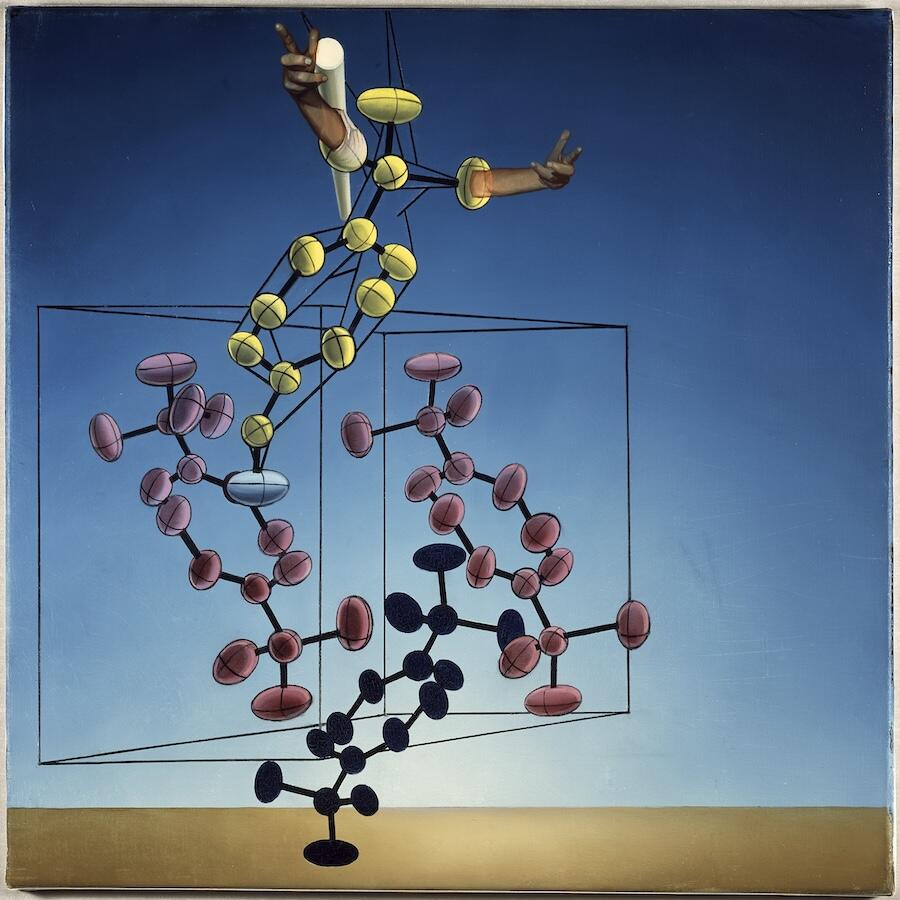

Launching in 2026, Fundació Gala–Salvador Dalí begins an ambitious new initiative that brings art and science into bold, generative dialogue. Led by Mónica Bello – former Head of Arts at CERN and curator of the 2022 Icelandic Pavilion – Platform Dalí will offer major grants for five in-house residencies and two fellowships each year, supporting artists as they develop proposals with one of Barcelona’s five scientific centres: the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre-National Supercomputing Centre (BSC), the Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO), the Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM-CSIC), the Institute of High Energy Physics (IFAE) and the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB). Confirmed artists so far are Tania Candiani (Mexico), Estampa (Spain), Israel Galván (Spain) and George Mahashe (South Africa).

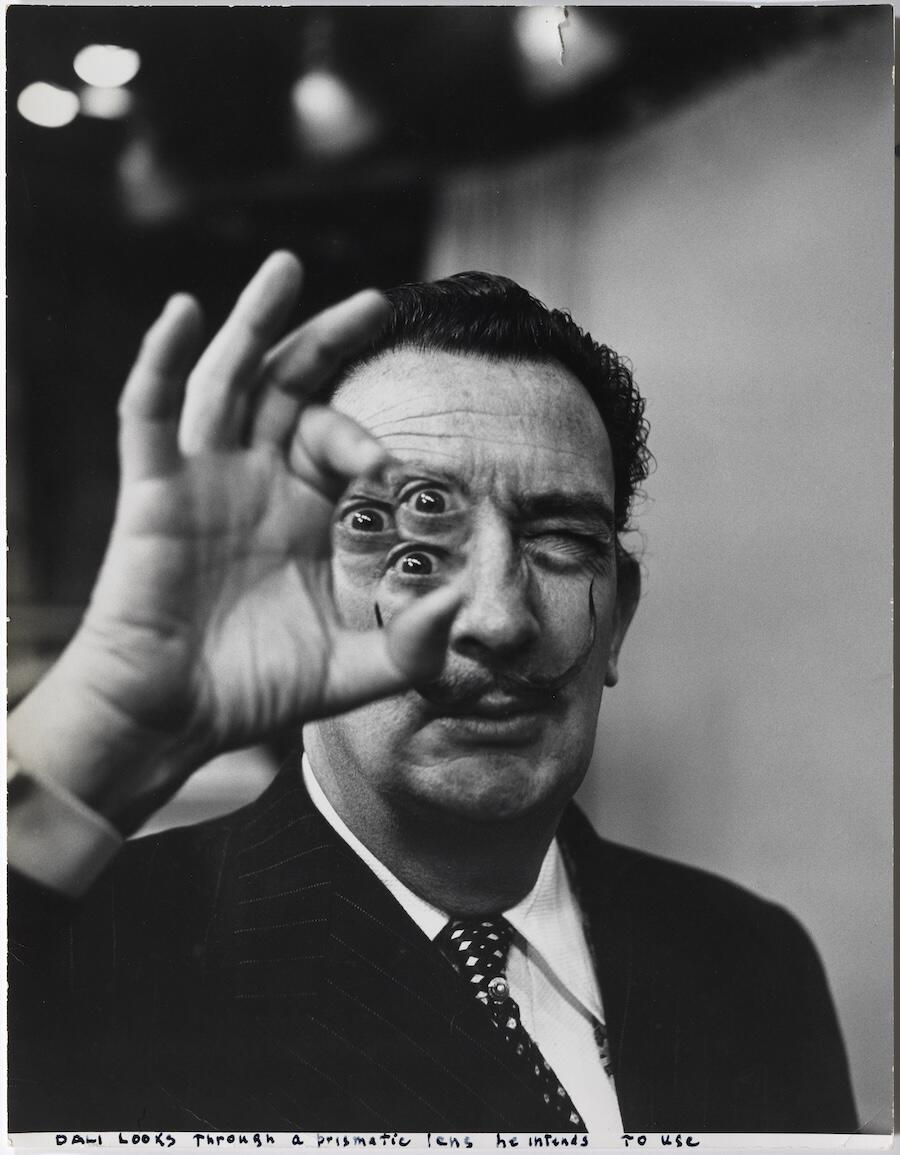

Salvador Dalí’s involvement with the empirical world is not widely known but Platform Dalí will reintroduce the pioneering surrealist as an avid follower of scientific discovery. Below, Bello reflects on her vision for the project and why, in her view, there’s no better moment for the world to turn to the artist’s restless curiosity.

AL Could you explain Salvador Dalí’s connection to science? It’s not something I was ever aware of.

MB [Upon accepting this new role at Fundació Gala–Salvador Dalí] I went to see some of Dalí’s paintings and sculptures and immediately noticed signs of his engagement with physics and mathematics. He was very well informed about what was happening in science and technology throughout his life.

For example, he visited James Watson and Francis Crick after they received the Nobel Prize for discovering the structure of DNA. After that moment, once he understood how to depict DNA with a certain level of rigour, he became confident enough to draw the double helix with striking precision – its molecules, its form – exactly as it was understood at the time. And then, of course, he began to invent his own interpretations.

AL Why do you think this important aspect of Dalí’s work was forgotten, or at least, not acknowledged by much scholarship on his work?

MB Dalí was never trying to be canonical – he was always breaking the rules. What’s interesting is that many contemporary artists are now engaged in rewriting belief systems, and reframing, redefining and shifting [their identity]. In many ways, Dalí was a precursor to this. Once artists begin working on this programme, I hope it will spark a deeper body of scholarship in [how Dalí’s interests in science influenced his art].

AL I am currently reading a book by Oxford professor Marcus Du Sautoy called Blueprints: How Mathematics Shapes Creativity [2025] which upturns the idea that science and art are binary disciplines. What have you observed in the scientists and artists you’ve worked with?

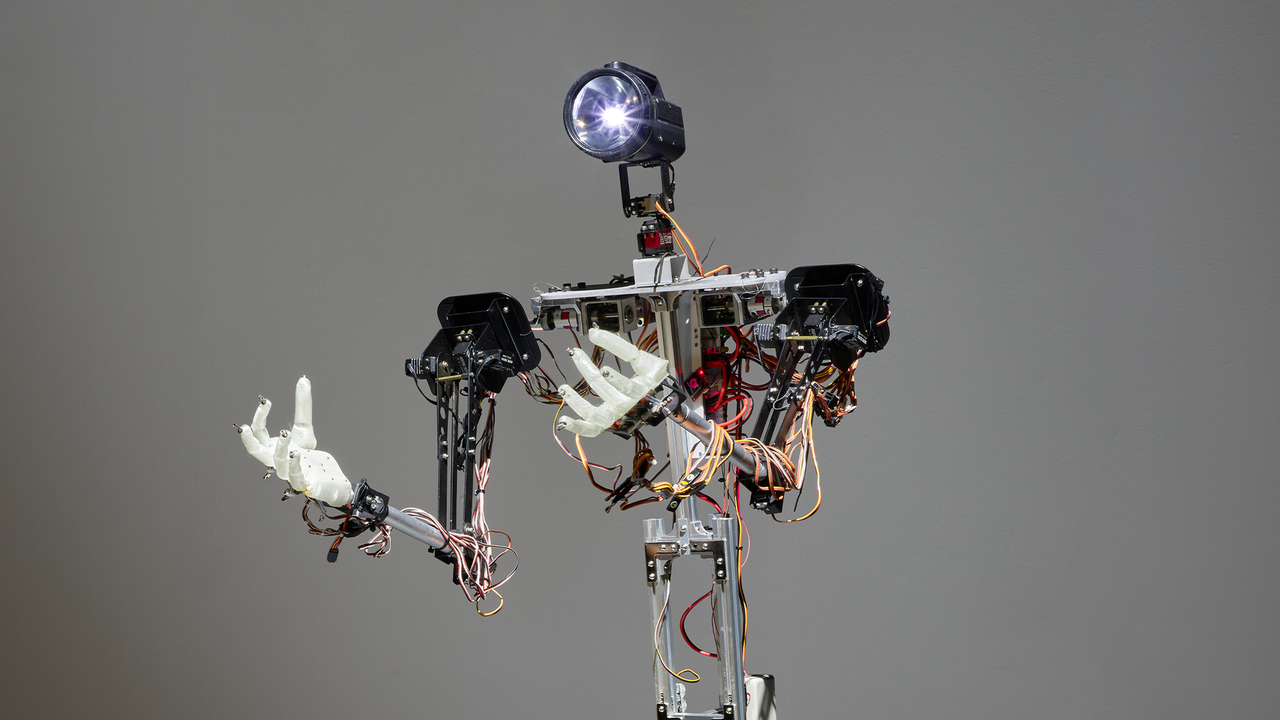

MB Many scientists are very obsessive. I’ve seen so many people go through existential crises: why do I care that the universe is expanding? Why are we radiated if we leave our planet? Why does life only exist on our planet? So, the benefit of a scientist working with an artist is that they see people who are also obsessed with questions they don’t have answers to. When artists have a question, they invent things. And scientists can tinker with machines that respond to a question. Craft is an important aspect of both disciplines.

AL Dalí casts a large shadow over this entire project. Won’t artists feel pressured to interact with his work in some way? How much freedom will they get?

MB When I was at CERN, getting artists to engage with particle physics was very demanding – precisely because the field pushes so far beyond ordinary human intuition. But Dalí’s work is playful because it treated the laws of nature as materials to be bent, stretched and reimagined. He was a provocateur, too. He showed the world, in a very visionary way, that being an artist is about being in dialogue with your surroundings. He moved from his hometown on the Costa Brava to Madrid, then Paris, then New York and he returned… He understood that moving through time and space was the most modern way of being an artist. He was very porous in terms of influences, and in many ways very queer; he was ambiguous about his sexuality. I don’t want artists to feel like they have to illustrate Dalí but rather to use him as an opportunity to think and create without constraint.

AL Why host this programme in Barcelona?

MB The reason we are bringing Dalí to Barcelona is because it is a scientific capital. Today, the definition of a scientific laboratory is inherently international – many of these spaces operate in large international networks. [In the same spirit,] Platform Dalí is also an international programme. Artists and scientists are nurturing something. There is an enrichment in what they do. Given the current climate, when institutions are losing their budgets, this project is going to be very generous [in enabling artists to think big].

AL I can see that Platform Dalí is a great opportunity for artists, but what do the scientists get out of this?

MB What is very important for us is that artists are in dialogue with a new discipline and with people who are involved in defining new ways to understand the world and its processes. Scientists are inventing the future, making the technologies for it, and they often feel overwhelmed by carrying the pressure of social responsibility. I want artists to be a medium and an ally for them to think about science and its implications differently. [For example], when a cosmologist spends time with a choreographer, they [are both encouraged to] consider gravity, space, time, movement and vibrations in different ways.

Find out more about Platform Dalí

Main image: Close-up of a computer in Institute of High Energy Physics (IFAE). Courtesy: Fundació Gala–Salvador Dalí