The Books Frieze Editors Couldn’t Put Down in 2025

From a reissued novel by Hélène Bessette to an anthology of 70 Irish photographers, our editors choose their favourite reads of the year

From a reissued novel by Hélène Bessette to an anthology of 70 Irish photographers, our editors choose their favourite reads of the year

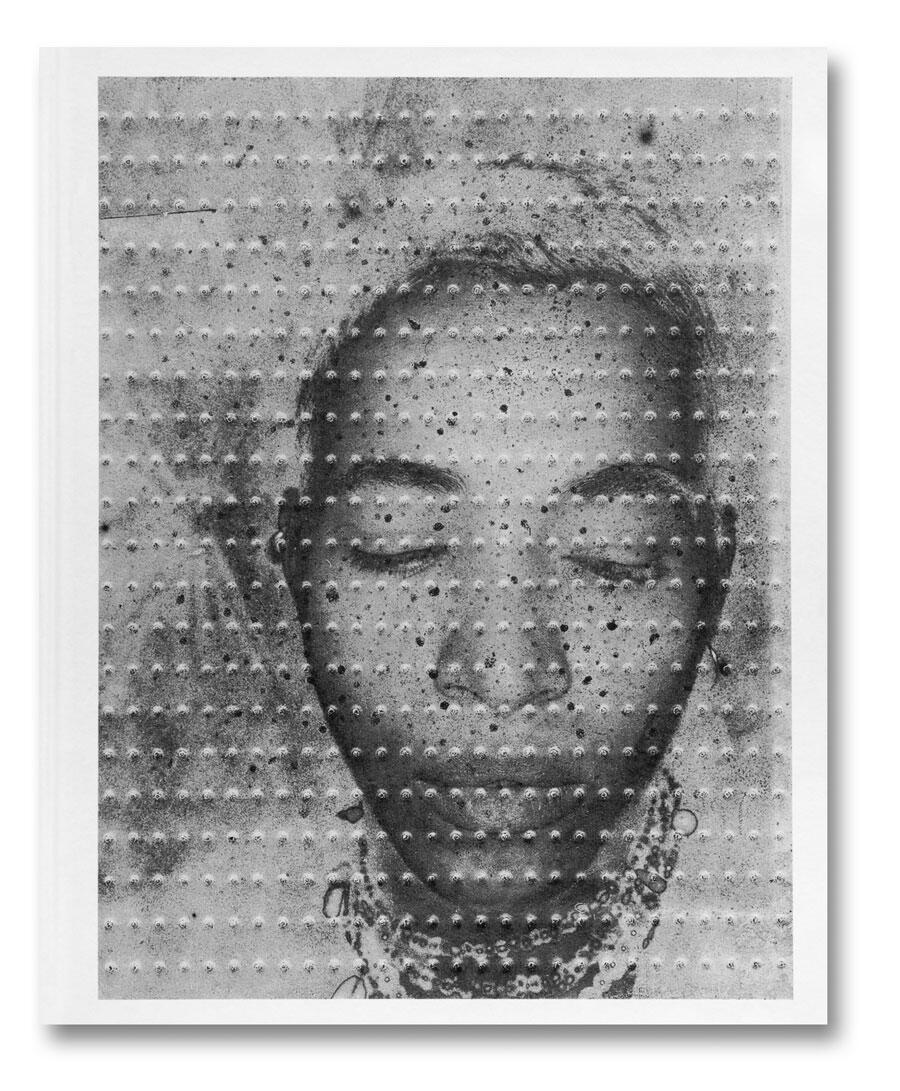

I Will Keep You in Good Company (2025) | Liz Johnson Artur

It has been a good year for artist self-publishing and independent presses. A few books stand out in my mind, but my choice here is Liz Johnson Artur’s I Will Keep You in Good Company, which reproduces pages and fragments from more than 20 of the artist’s personal workbooks. She has been creating and preserving these handmade volumes since the early 1990s. I really enjoyed how layered and tactile the pages feel, more like a beautiful working document than a pristine photobook. – Sean Burns, Assistant Editor

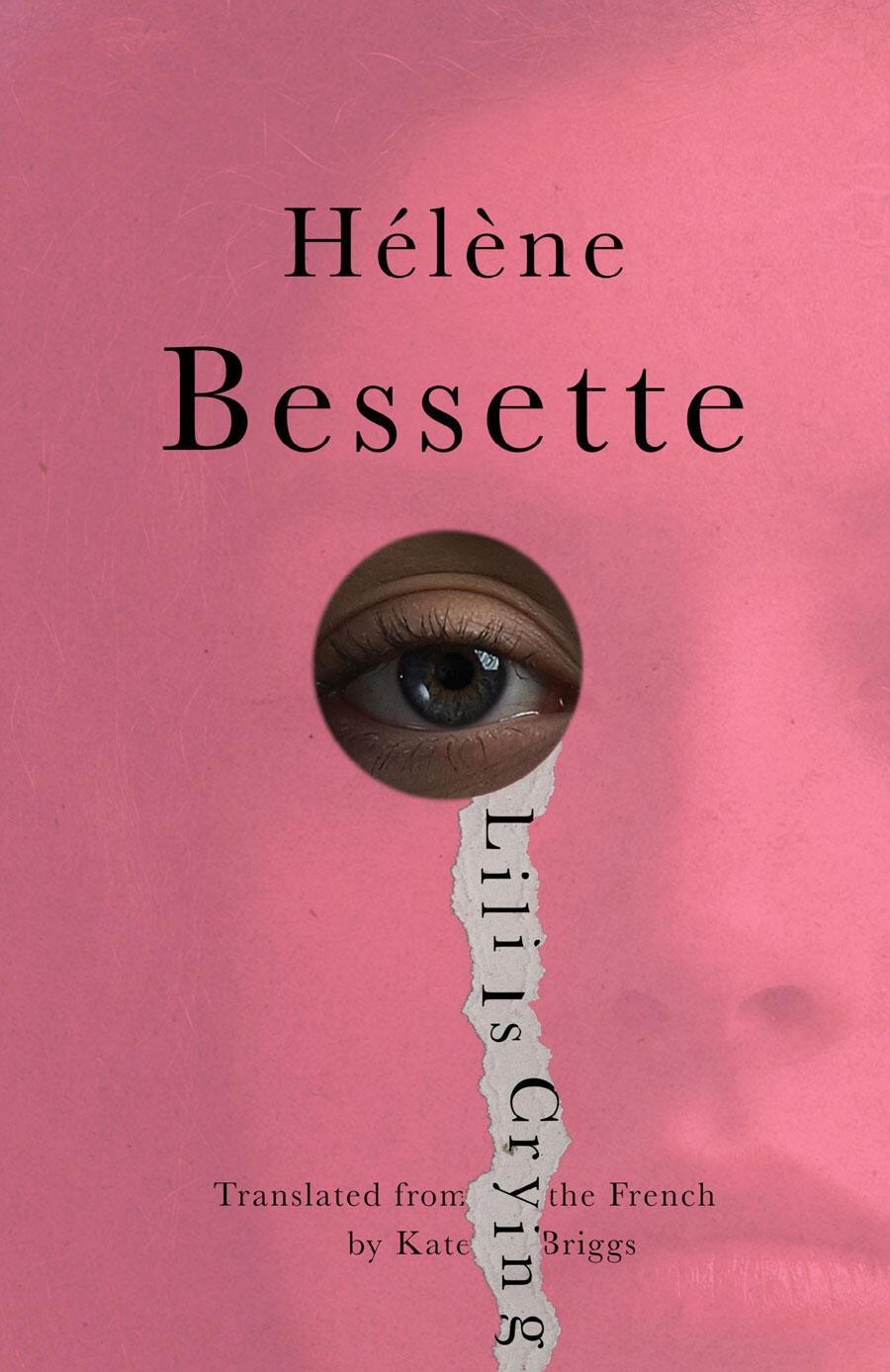

Lili is Crying (1953/2025) | Hélène Bessette

Encountering Bessette’s debut novel, originally published in 1953 and translated from the French by Kate Briggs, made me think that we’d all be writing more like Bessette if only we’d had access to her earlier. Lili is Crying is the spiritual successor to late Virginia Woolf, like To the Lighthouse (1927) or The Waves (1931) filtered through a nouvelle roman machine. The language is stripped down, lineated like a poem; time collapses and every word is loaded. This novel is short – you’ll think you can speed through it – but you’ll soon find yourself lost in the fascinating pull of Bessette’s prose and her painful depiction of a catastrophic world. – Marko Gluhaich, Senior Editor

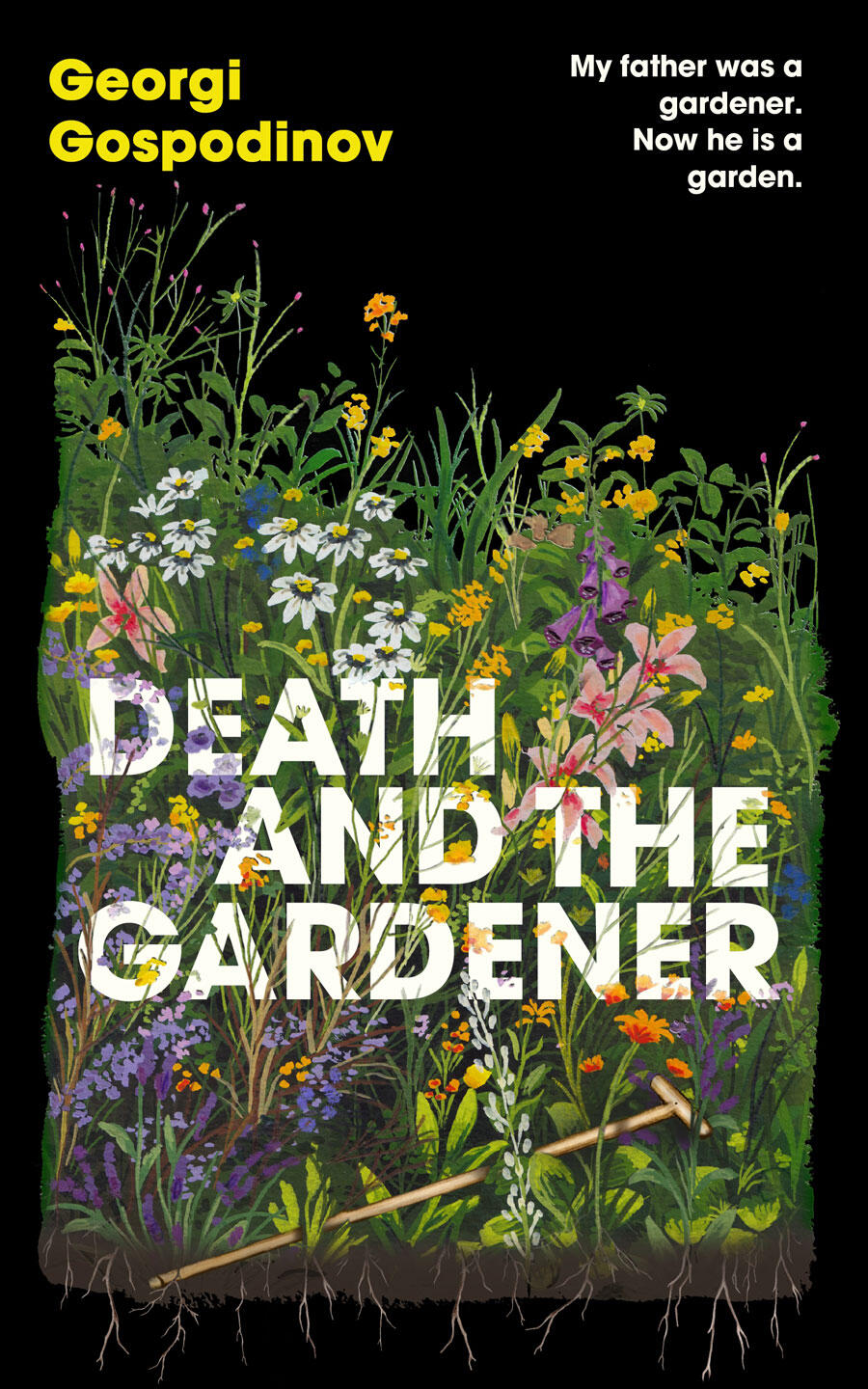

Death and the Gardener (2024/25) | Georgi Gospodinov

Georgi Gospodinov’s latest novel to appear in English is a tender meditation on what he calls the ‘botany of sorrow’. Told through the lens of a narrator who, like Gospodinov, is a writer, the novel traces his beloved father’s death alongside his quiet devotion to gardening – a practice that becomes both metaphor and memorial. Emotive vignettes, rich in literary reference and spanning from Ithaca to present-day Sofia, skilfully acknowledge the non-linearity of loss. Gospodinov rebuffs the toxic patriarchal culture of the distant, disciplinarian father propagated under communist rule, portraying instead a gentle man defined by care: ‘My father managed to turn every place into a garden, every house into a home.’ The novel becomes a testament to the silent, small acts of service through which we express love. Like much of Gospodinov’s work, Death and the Gardener reflects on storytelling as a form of survival. What happens, he asks, when the custodians of our past begin to disappear? – Ivana Cholakova, Assistant Editor

Audition (2025) | Katie Kitamura

An actress meets a younger man for lunch and notices her husband walk into the same restaurant, even though he should be in a different part of town. From this starting point, Katie Kitamura’s latest novel, Audition, morphs into an exploration of performance, legibility, the complexities of relationships and what we owe to those we love. Audition probes the slippery gaps between fact and fiction, our interior and exterior selves: what we know of ourselves, and how we are perceived by others. There are several shifting points and twists, and the book offers no clear-cut resolution. This is a rare novel that I wanted to immediately reread, to see what I might have missed, to try and spot the clues the author may have been offering throughout. Kitamura’s mastery of language and plot means that Audition is a book that will stay with me for a long time. – Vanessa Peterson, Senior Editor

Dog Days (2025) | Emily LaBarge

‘Trauma’, Emily LaBarge writes, ‘is a narrative problem.’ You could say that her new release, Dog Days, picks at that Gordian knot, but it feels truer to say that it holds the knot up to the light, that it finds ways to live (and write) inside it. LaBarge interweaves memoir with psychology research and ruminations on art, literature and cinema to reckon with the personal cataclysm’s resistance to temporal and narrative structure: the way it shatters, scrambles and upends storytelling itself. In the process, she finds the basis for another literary form. It’s a remarkable first book, a cross-genre experiment of startling beauty and insight. – Cassie Packard, Assistant Editor

Perfection (2022/25) | Vincenzo Latronico

Set in the 2010s, this spare novel follows Anna and Tom, a millennial graphic designer couple who live in a perfectly curated Altbau apartment – all honey-coloured wooden floors and monstera plants – which they often sublet for an exorbitant fee. As they watch their adoptive city change – friends are priced out, bars close and neighbourhoods transform – we see the pair grow increasingly restless with their picture-perfect lives. Within my social circle in Berlin, Latronico’s novel was easily the most talked-about book of the year. Some hated it. But that’s hardly a surprise, given its unflattering portrait of us – that is, expat creatives constantly apologizing for their poor German. – Chloe Stead, Associate Editor

Shadow Ticket (2025) | Thomas Pynchon

It has been 12 years since Thomas Pynchon published Bleeding Edge (2013), his millennial caper about the dark side of the internet, and many of us had given up hope of ever seeing another from the 88-year-old novelist. Then, this autumn, Shadow Ticket was published. The novel is about a Milwaukee private investigator whose search for a missing cheese heiress draws him to fascist Europe. While most reviews compared this relatively slim novel to Pynchon’s own epics, including V. (1963) and Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), I kept thinking of Henry James’s The Ambassadors (1904) – the master’s portrait of an American businessman who stands at the threshold of a vanishing world. There’s something of that in Hicks McTaggart’s journey to Hungary. While some critics complained of the novel’s breathless pace, I read in Pynchon’s speed the anxiety of a writer who knows we are running out of time. ‘A deep rumbling felt more than heard passes through the invisible world and around the edges of this one,’ he writes of his twilight Budapest. ‘From beyond any zone of civic safety something has begun to pulsate, soul-strumming and growing louder …’. – Andrew Durbin, Editor in Chief

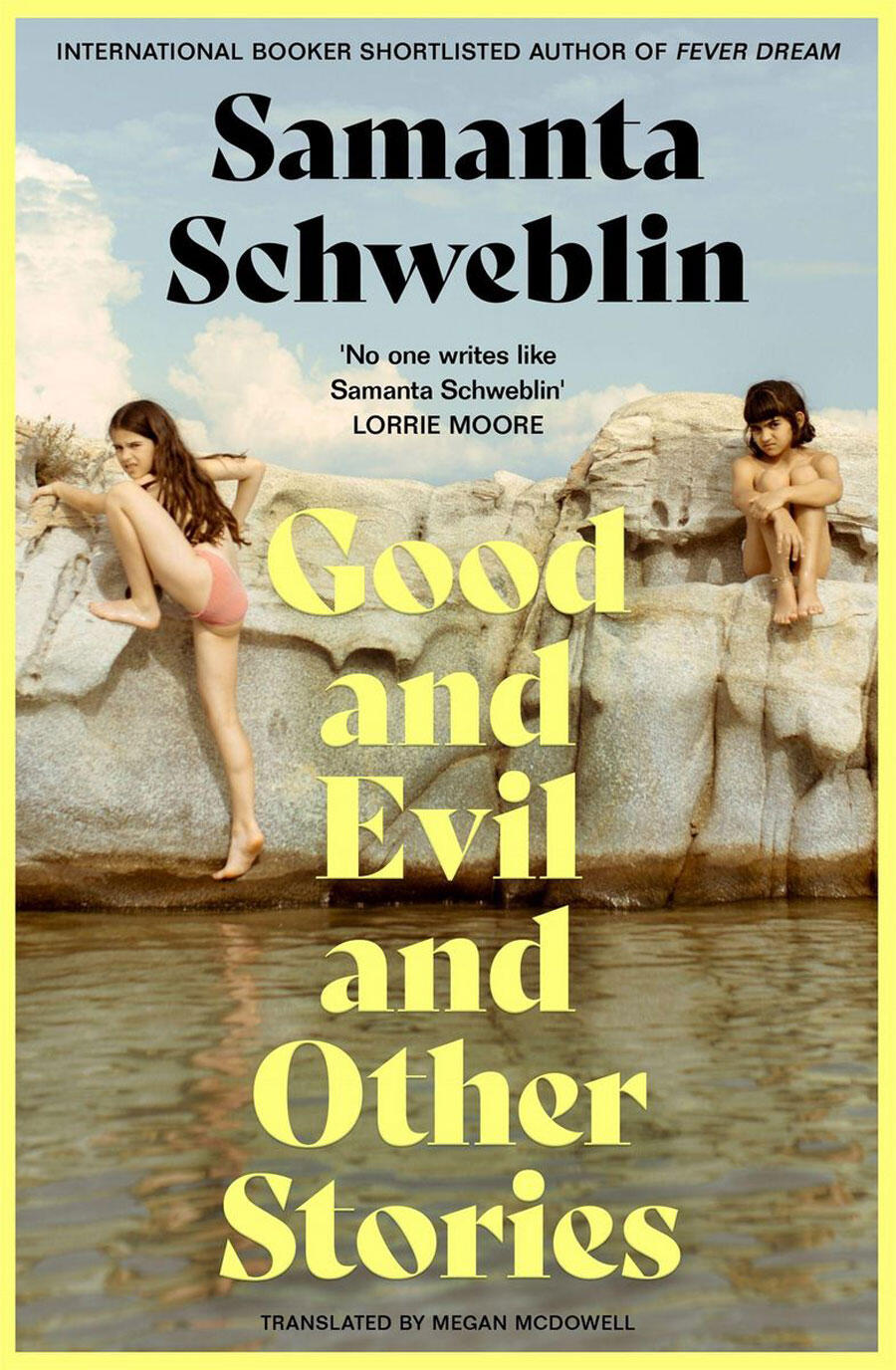

Good and Evil and Other Stories (2025) | Samanta Schweblin

When you’re six years old and resisting sleep, late-night shadows will lend limbs to harmless bedroom objects. A coat suspended on the back of your door becomes the ghastly culprit of enduring nightmare fuel. For Argentine writer Samanta Schweblin, it is less overactive imagination, more loss and tragedy that muddy our experiences of the arbitrary. This latest collection of short stories – her third translated into English by Megan McDowell – weaves unsettling connections between humans, animals, devotion and fear with a delightfully macabre tone. I was disarmed by the stand-out tale ‘An Eye in the Throat’, where a boy swallows a battery and gets a tracheotomy-turned-gateway-to-new-consciousness. His parents’ guilt and exhaustion will cling to you. As will the haunting presence of William the cat and the many horses throughout. Peculiar, raw and precise, these stories marvel at ambiguity until it is something much greater – and eerier. Stare at the title for the warning to appear: this is not good and evil (and other stories), these are stories of good, evil and the other. – Lottie Gale, Editorial Production Assistant

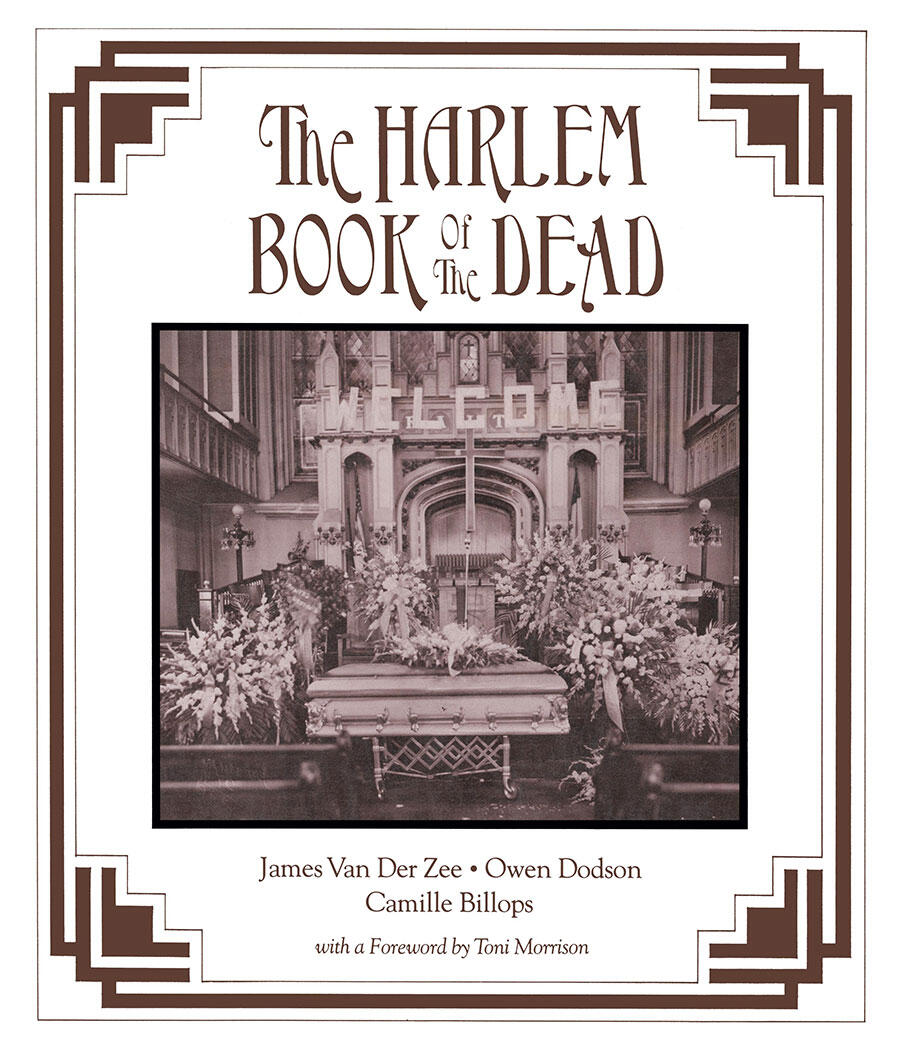

The Harlem Book of the Dead (1978/2025) | James Van Der Zee

Organized by artist and filmmaker Garrett Bradley, this reissue revives James Van Der Zee’s exquisitely sombre and eerily strange photographs of Black funerary rites in Harlem, alongside Owen Dodson’s brusque verse and a new afterword by scholar and writer Karla F.C. Holloway. An interview with Van Der Zee by artist and sculptor Camille Billops, who originally conceived the book, weaves throughout – a rolling text that ranges from the photographer’s life to the mundane and profound techniques of his craft. A chronicle of Black life, these solemn images are both difficult to look at and utterly rapturous, often splicing Christian funerary imagery into portraits of the dead to create ghostly, haunted compositions that, as Toni Morrison wrote in her foreword to the original edition, are truly ‘sui generis’. Today, the book feels revelatory not only within Van Der Zee’s oeuvre but for uncovering something mystical about Black mourning. It serves as a powerful counterpoint to the dominance of soulless, abject imagery of Black death, offering a new way of honouring the dead. As Holloway concludes in her afterword: ‘This is what it means to compose an afterlife.’ – Terence Trouillot, Senior Editor