Barcelona’s Infamous La Modelo Prison Opens Up Its Repressed Memories

Now open to the public, the prison, modelled on Bentham’s panopticon, gives insight into the tumultuous history of working class uprisings

Now open to the public, the prison, modelled on Bentham’s panopticon, gives insight into the tumultuous history of working class uprisings

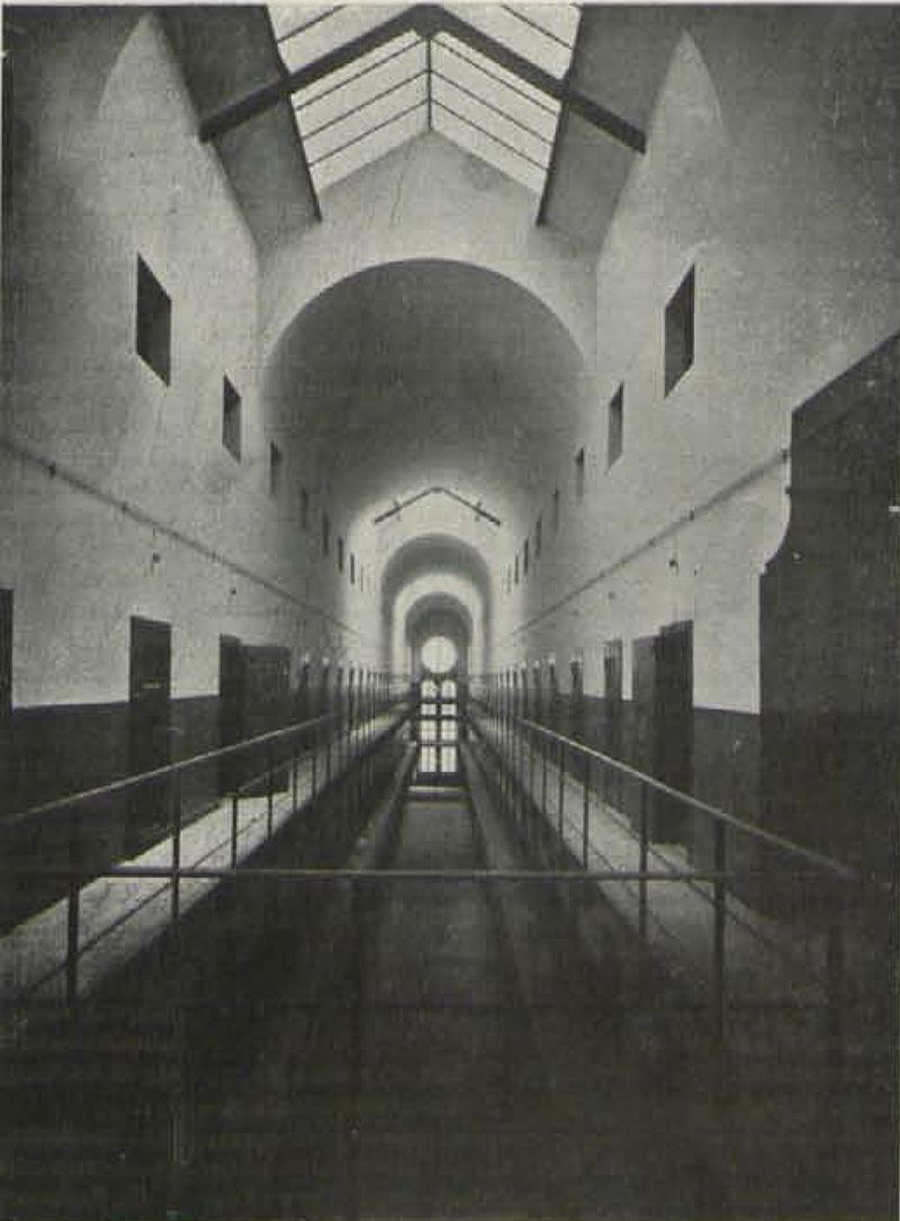

A cool breeze flows through the panopticon of the La Modelo prison in Barcelona. Past rusty corridors and a renovated courtyard, air trickles into the street by way of an open gate. Footsteps, voices and birdsong reverberate in the empty halls. Some cell doors are open, most remain under lock and key.

The mix of fresh air and carceral architecture seems appropriate to Spain’s current political climate. Prompted by a court ruling on a large-scale corruption scandal, the Spanish Socialist Party recently ousted Mariano Rajoy’s right-wing government with a successful no-confidence vote, the first in the country’s history. Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez now presides, from the weak position of a minority government, over a country that is falling apart due to successive economic, social and political crises, including a conflict over self-determination here in Catalonia. To address these challenges, Sánchez will have to strengthen a fragile pact with the radical left and regional nationalists in Catalonia and the Basque Country, which put him in office.

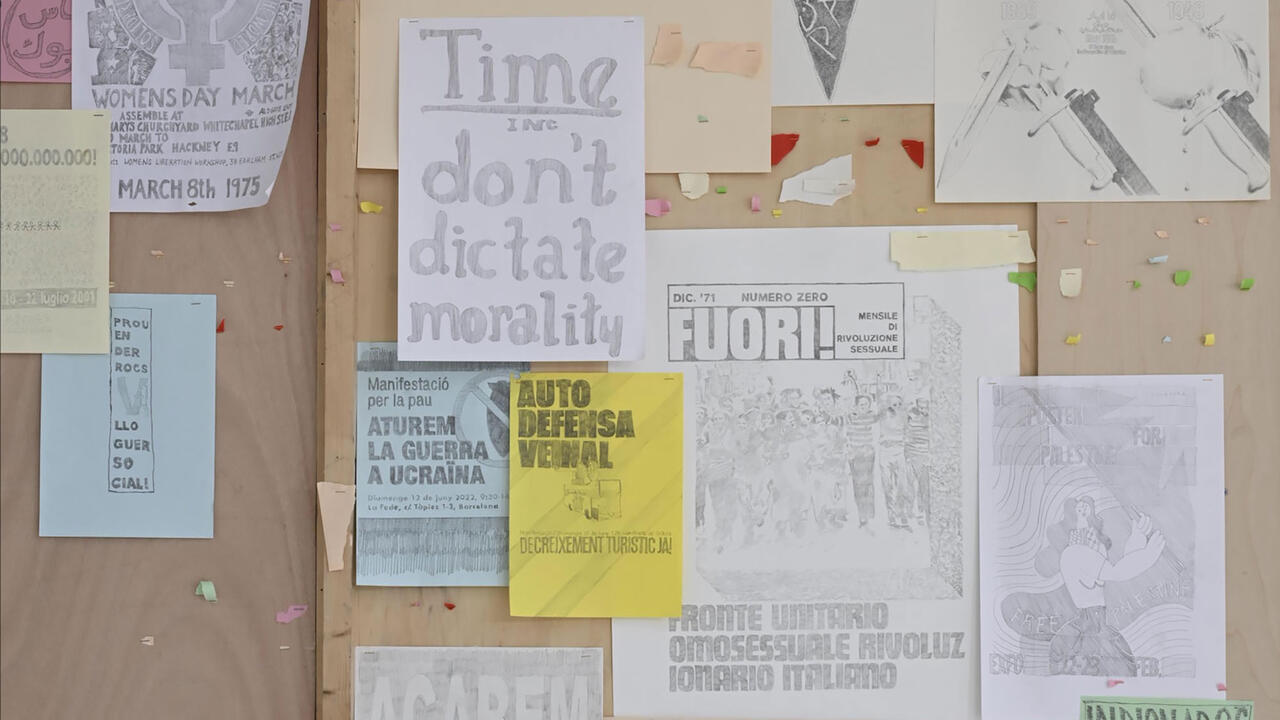

It’s not an easy task. An exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (CCCB) shows just how toxic the political situation has become. Censored by ARCOMadrid when it was due to be shown there in February (the art fair requested its removal to avoid ‘harming the visibility’ of other works), Santiago Sierra’s Political Prisoners in Contemporary Spain (2018) consists of 24 black and white photographs. Their subjects, protagonists in a number of recent political conflicts, have all been incarcerated by the Spanish state. Each face is obscured by thick grey pixels, each person referred to only by number. For context, Sierra describes the charges with passing references to the anarchist, environmentalist, syndicalist or secessionist motivations of their actions. What emerges is a map of the political conflicts that have been displaced into Spain’s judicial sphere, the ideologies targeted by the country’s penal system.

Leftist militants have often referred to Spain as ‘a prison of peoples’, an expression nicked from Lenin’s 1914 text ‘On the National Pride of the Great Russians’. Nowhere does that phrase resonate quite like it does in La Modelo, as its cells contained countless figures from Spain’s historic struggle against dictatorship: anarcho-syndicalists like Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia, antifascist freedom fighters like Salvador Puig Antich, political figures such as Catalan President Lluís Companys, and hundreds of lesser-known dissidents. It is this still-repressed memory, along with the sorry state of the facilities, that led the governments of Catalonia and Barcelona to shut down the prison on 8 June 2017. How the space will be used, what will be kept and what demolished, is being decided directly by citizens through a formal participatory process.

In the meantime, La Modelo is being exhibited to the public, opening a space to reflect on what it enclosed. Displaying still images of dilapidated corridors to passers-by, it gives a fleeting sense of the negligence with which life inside was treated. There are no people in these photographs, no credits, titles or descriptions accompanying them. We must imagine the world contained, drawing only from what we see. An empty mess hall here, a methadone clinic there. ‘This is where I used to eat,’ someone has scrawled on the canvas, marking the spot at the table with an X. We can’t be sure if it is true about the author, but it is certainly true about someone. One wonders what a visit must be like for the families of inmates.

As the name suggests, the prison’s crumbling walls hid a model. At the time of its opening in 1904, La Modelo was proposed as an improvement over the squalid conditions typical of Spanish prisons, where dissidents and the criminalized urban poor were corralled into neglected, densely populated spaces alongside murderers and rapists. There they would mingle and mix, often spreading disease, often sharing rumours, news and ideas. They died at an alarming rate, and they rioted.

La Modelo brought Jeremy Bentham’s well-known panoptical design into a tumultuous history of working class uprisings and dictatorial repression. By separating the prisoners and making them observable, countable and classifiable, it made sickness harder to spread, riots more difficult to instigate and prisons easier to control. It didn’t work for long, however. The first riot within its walls took place two years after it opened, then again in 1919, when anarchist prisoners, who had turned the prison into a makeshift school of libertarian communist thought and practice, protested for better food and better hygiene. Perhaps the most legendary uprising took place in 1984, when Juan José ‘El Vaquilla’ Moreno Cuenca – a popular Spanish gitano depicted as a Robin Hood-like folk hero in a popular series of films by José Antonio de Loma – took the keys from a prison guard and opened the cells of the fifth wing, demanding better conditions, access to the media and heroin for the addicted.

The corridors are much quieter now, the buzzing drone of harsh fluorescent lights softly punctuated by the steps and whispers of cautious visitors. This relative stillness makes the distressed, unattributed art on the walls by inmates all the more jarring. In one cell, holes left by chunks of fallen brick have been turned into disturbing creatures not unlike those imagined by David Cronenberg. In another, a poet puts the prison at the centre of a colonized world: Around us, the madness of empires continues. An unsettling thought since, though originally built outside Barcelona, urban expansion has brought La Modelo into the city centre.

Like the decision to shut the prison down, the participatory process to decide its future has the support of practically all the same political actors that ousted the previous Spanish government. With municipal elections just a year away, those same actors will likely squabble over who gets credit for this fairly popular decision. And they will do so at high volume and in polarized terms. But perhaps more than loud voices and political calculation, profound transformations ask for deep listening and a certain openness to mutation. Perhaps the current stillness in La Modelo might be seen as an invitation to participate in a collective moment of silence, a reflection on temporalities now beyond our own.

This idea is at the heart of ‘Silenci/s’, an exhibition at Barcelona’s Arts Santa Mònica curated by Jordi Tolosa, which features several artists’s depictions of the concept of silence. Across plastic mediums, silence is positioned as the background upon which all time and all things are articulated. In 7 contemplations (2016), video artist Toni Serra (Abu Ali) speaks to silence as what allows our gaze at the exterior to shift inward. ‘Through contemplation,’ he writes in the accompanying text, ‘we allow the other to soak in, like gentle rain.’

It is a beautiful image, one that evokes the dissolution of unnecessary walls. And it makes me think that it may very well be that La Modelo has nothing worth keeping. Not the cells, not the courtyard or the stories. Certainly not the panopticon. And even less, a world built on enclosure and containment.

Main image: La Modelo Prison, Barcelona, 2017. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons