Why Central Asia Takes Centre Stage

As new institutions launch in Almaty, Bukhara and Tashkent, a Slavs & Tatars-curated show at No.9 Cork Street reframes the region’s art history

As new institutions launch in Almaty, Bukhara and Tashkent, a Slavs & Tatars-curated show at No.9 Cork Street reframes the region’s art history

This month, ‘To everything spurn, spurn, spurn’, curated by the international art collective Slavs & Tatars and Asya Yaghmurian for Artwin Gallery, will bring trailblazing work by young Central Asian artists to Frieze’s London exhibition space, No. 9 Cork Street. It’s just one vibration from an arts boom transforming the region. A slew of high-profile openings and events there this season include two private ventures in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s cultural lodestar: the Almaty Museum of Arts and the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture (CCC). Meanwhile, in Uzbekistan, the government-backed Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) has opened in its capital city, Tashkent, alongside a major new biennial in the historic Silk Roads stop of Bukhara, curated this year by Diana Campbell Betancourt.

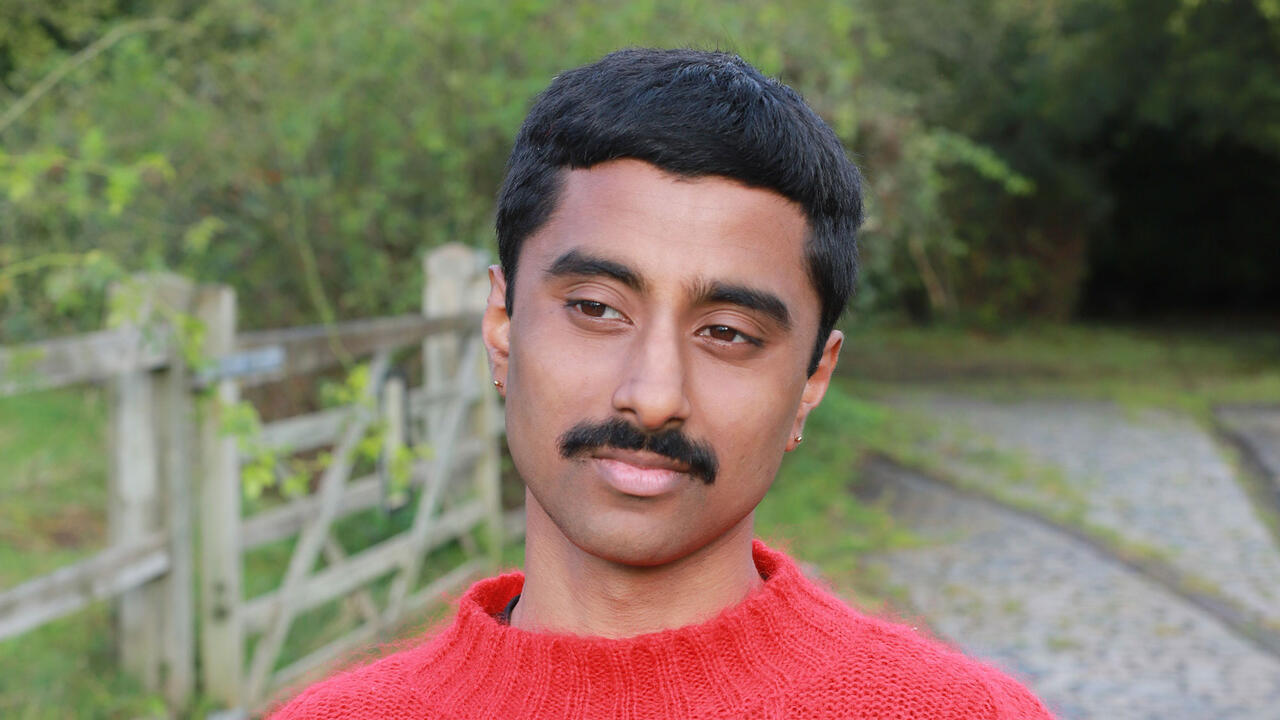

For Payam Sharifi of Slavs and Tatars, the regional specifics of Central Asia – which officially includes the republics of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan but stretches further culturally – make it particularly relevant on the contemporary global stage. ‘The idea of being in-between identities is very important,’ Sharifi says. ‘The borders between these countries are so artificial, drawn by hand by Stalin 70 years ago. There are many faiths, including shamanic ones, and all Central Asian artists speak two or three languages.’

According to Sharifi, the young guns showcased in this exhibition have a different outlook to the first wave of Central Asian artists who emerged in the early 2000s, such as acclaimed video artist Almagul Menlibayeva or conceptualist Erbossyn Meldibekov. ‘This new generation want to move beyond the “post-Soviet” epithet,’ he says. Rather, ‘they share an interest in ritualistic or craft traditions, but with a contemporaneity and sharpness to how one revisits one’s past.’ Madina Joldybek, for example, makes textile works in which maternal breasts bloom, addressing the creative challenges of art-making and motherhood. Nazilya Nagimova uses wool-felting techniques inspired by those of the ancient nomadic Tartars to fashion giant butterflies, exploring issues of ecological fragility.

After what Sharifi describes as a ‘lost period’ between generations, with little happening beyond grass-roots ventures, Central Asia’s two most powerful countries are supercharging their art ecosystems with distinctly different approaches. In Almaty, it is independent patrons developing opportunities for artists and nurturing fresh audiences. Founded by businessman Kairat Boranbayev in 2018, the Tselinny CCC’s activities have previously included publishing and a ‘scholar in residence’ programme. Its director, Jama Nurkalieva, explains that ‘a major goal for us was to reflect on years of blank history after the Soviet regime was gone, when our national identity wasn’t clear’.

Looking to Central Asia’s nomadic traditions of music and storytelling, Tselinny CCC’s new permanent space, developed by British architect Asif Khan in a former Soviet-era cinema, will be a platform for multiple mediums, including its Korkut Sonic Arts Triennale, the second edition of which will be held in 2026. The opening exhibitions at the venue riff on the myth of Nurtole, a supernatural figure who banished snakes by playing his kobyz (a kind of stringed instrument). Musical performances by the experimental collective qazaq indie will take place within an exhibition of work by Dariya Temirkhan and Gulnur Mukazhanova. ‘They’re reinterpreting the idea of coming back home,’ says Nurkalieva.

Inga Lāce, chief curator at the new Almaty Museum of Arts, underlines its role in developing audiences, introducing ‘contemporary art, global art histories and artists to a wider public’. It houses 700 works by Central Asian artists from the collection of its founder, Nurlan Smagulov, shown alongside international heavy-hitters, including Alicja Kwade, Jaume Plensa and Yinka Shonibare, who has a new outdoor sculpture commission. Strengthening its European connections, it plans symposiums with London’s Tate Modern and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Lāce’s opening exhibition, ‘Qonaqtar’ (‘guests’ in Kazakh), draws from the collection to tell the story of the region’s recent art history, beginning with those who emerged during Nikita Khrushchev’s post-Stalin thaw, like Aisha Galimbayeva, Kazakhstan’s first professionally trained woman artist, who was also a film costume designer and archivist of national dress, and whose paintings explore the stages and roles of women’s lives. Contemporary names include Kyrgyz artist Chingiz Aidarov, whose video Snail (Spiral) (2021) sees him push a roll of migrant workers’ sewn-together mattresses through a Moscow suburb.

In Uzbekistan, the Tashkent CCA and Bukhara Biennial are just two initiatives |in a huge government-led programme of cultural renewal aimed at expanding the country’s arts industry, affirming its heritage and boosting its presence abroad as it assumes a more significant role in global trade. Gayane Umerova, chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF), has overseen the development of the CCA by French architecture Studio KO in a 1912 diesel generating station that once powered the city’s trams. She has commissioned the new biennial, led the first Aral Culture Summit in the spring of 2025 and, since 2021, has commissioned the Uzbekistan pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Having begun with residencies for international artists last year, the Tashkent CCA will soon announce its exhibition and education programme to ‘reinforce Uzbek culture and potential’, Umerova explains. She reflects that there was little understanding locally of what contemporary art could be when the ACDF began its work eight years ago. ‘Our art education was very academic,’ she says. ‘It was about creating with your hands. The younger generation wanted to work in a multidisciplinary way. We’re trying to change the stigma around this.’

This year’s inaugural Bukhara Biennial, ‘Recipes for Broken Hearts’, is, in this sense, a clarion call. Themed around hospitality, it features collaborations between local chefs and craftspeople with international names and homegrown talents. The famed Uzbek chef Pavel Georganov has worked on separate culinary projects with art superstars Subodh Gupta and Carsten Höller. Slavs and Tatars have teamed up with ceramicist Abdullo Narzullaev on an installation exploring the divine gift of the melon. Younger Uzbek artists include the London-based Aziza Kadyri, who is creating work for her home country for the first time.

‘Bukhara is historically a place of pilgrimage and trade with different cultures,’ says Umerova. ‘It has the biggest number of artisans across different fields. The biennial isn’t just about Central Asia, but the Global South. We work with the Middle East, China, Japan and Korea. It’s a great moment for us to embrace that.’

For Sharifi, what makes Central Asian art so current and so compelling is its deeply embedded concerns. ‘Unlike in the urbanized West,’ he says, ‘questions of environmental fragility have been part of society [here] spiritually and intellectually for hundreds of years, be it living on the steppe or the disappearance of the Aral Sea. This is not a recent awakening. It doesn’t feel forced. It’s not a trend.’

This article first appeared in Frieze Week London 2025 magazine under the title ‘All Eyes on Central Asia’.

Further Information

Frieze London and Frieze Masters, The Regent’s Park, 15 – 19 October 2025.

Tickets are on sale – don’t miss out, buy yours now. Alternatively, become a member to enjoy premier access, exclusive guided tours and more.

For all the latest news from Frieze, sign up to the newsletter at frieze.com, and follow @friezeofficial on Instagram and Frieze Official on Facebook.

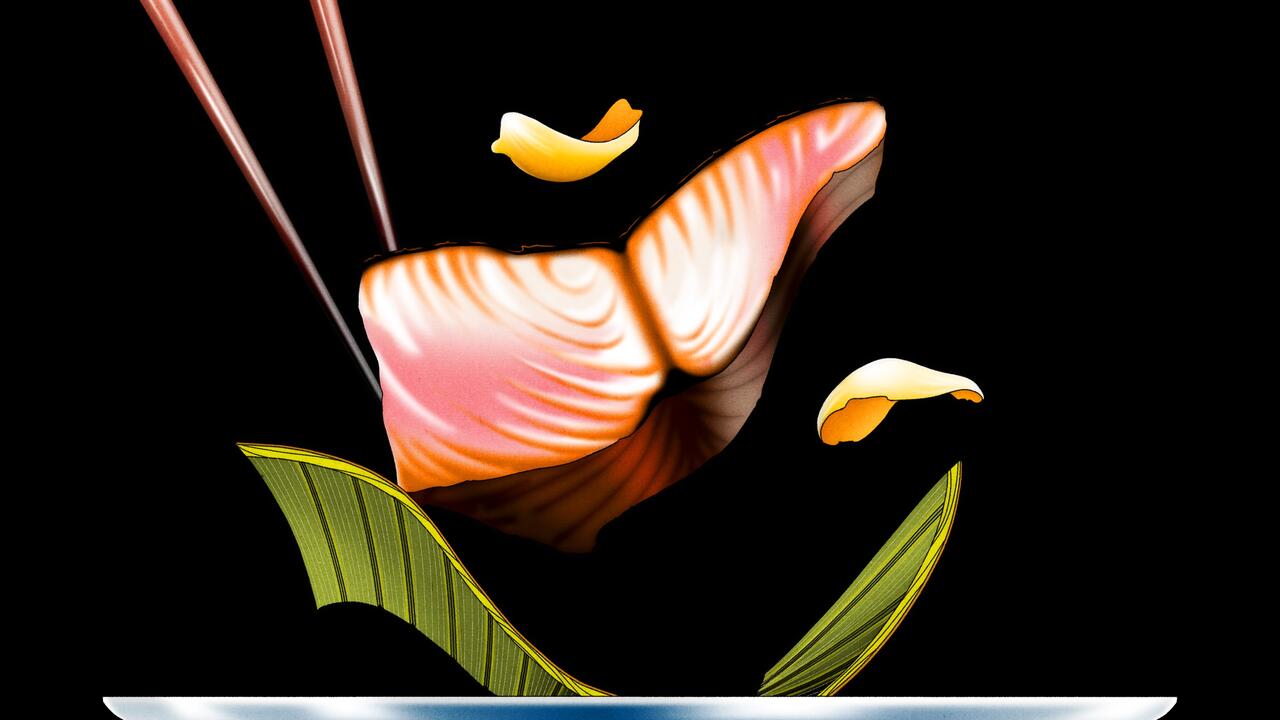

Main Image: Javkhlan Ariunbold, Turn of Seven Suns, 2024. Oil on wooden panel, 1.2 × 2.8 m. Courtesy: the artist and Artwin Gallery, London