Frieze Masters Podcast 2025, Episode 6: Twisted Classic | Glenn Brown on Collecting, Displaying and Distorting Old Masters

The sixth episode with Glenn Brown and Arturo Galansino is presented in collaboration with dunhill

The sixth episode with Glenn Brown and Arturo Galansino is presented in collaboration with dunhill

‘Every time you put a mark on a painting and you can’t take it off, you are running the risk of destroying the painting,’ says artist Glenn Brown. ‘But that’s what makes it exciting to paint.’

In the sixth episode of the Frieze Masters Podcast 2025, British artist Glenn Brown – who has pioneered the use of visual appropriation in his work – and curator Arturo Galansino discuss the jeopardy and excitement of mark-making, and what it means to collect, display and distort the work of old masters.

Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and the Frieze Masters Podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with dunhill.

About the speakers

Glenn Brown CBE is a British contemporary artist known for the use of appropriation in his paintings. His solo presentation was also a highlight of the Studio section at Frieze Masters 2025. He is joined by Arturo Galansino, art historian, curator, director general of the Palazzo Strozzi Foundation in Florence and this year’s curator of the Frieze Masters Talks programme.

About the Frieze Masters Podcast

The Frieze Masters Podcast is back for 2025, bringing you seven conversations across art history curated by Arturo Galansino (Director General of Palazzo Strozzi Foundation in Florence).

Entitled ‘Woven Histories’ and recorded live at Frieze Masters 2025, this year’s series features artists, curators and thinkers, whose conversations weave together geographies and chronologies, and challenge us to look at history in new and unexpected ways.

Topics range from the evolving relationship between fashion and art to the role of the archive in Black history, the last Mughals and their cultural influence in India and the enduring inspiration of the old masters and renaissance art on contemporary making. Speakers include artists Tracey Emin, Glenn Brown and Antony Gormley, museum directors and curators Nicholas Cullinan, Émilie Hammen, Elizabeth Way and Carl Strehlke, and writers Edward George, Matthew Harle, Christopher Rothko and William Dalrymple.

Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and the Frieze Masters Podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with dunhill.

Transcript and Images of Works Discussed

Emanuela Tarizzo: Welcome to series four of the Frieze Masters Podcast, brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with Dunhill. I’m Emanuela Tarizzo, Director of Frieze Masters, and this podcast brings to you our collection of talks from this year’s Frieze Masters fair.

In this episode, Arturo is joined by British artist Glenn Brown who has pioneered the use of visual appropriation in his work. Glenn’s work was also a highlight of the Studio section at Frieze Masters 2025, where he showed paintings that explored the idea of historical reinvention. Together Arturo and Glenn discuss collecting, displaying, and distorting the work of old masters and they ask ‘what can the greats of the past tell us about the role of the painter today?’

Here’s Arturo to introduce this week’s talk.

Arturo Galansino: Today we are speaking with Glenn Brown, one of the most interesting and cultivated painters of our times. The title is Twisted Classic, because what Glenn does is actually to transform through the practise of the copy, the old master’s paintings, drawings, and prints.

Glenn is going to speak about his very complex practise, and about his taste, because Glenn is also a collector and recently opened a space where his works are displayed alongside to the old masters he collects. As a collector, I’m sure Glenn will also tell us something about the desire which drives all the collectors to purchase some objects. We are at the Frieze Masters fair, I think it’s the perfect place to talk about that.

For Glenn I feel some old master imagery became a kind of obsession. We can see his obsession in the very complex practise of his painting, and also you can feel his unlimited love for these objects that he keeps watching, observing, and tries to enter the practise of the old masters. I hope our public will enjoy this talk because it will be very clear how contemporary art owes a big dept towards old master painters and draughtsmen. Speaking with Glenn, this will be very very clear.

AG: Okay. About your practice, Glenn. You draw from artist history, right? Transforming the paintings radically. How do you decide which old master is the good one to be twisted, reinvented, revisited?

Glenn Brown: I mean, I love such a broad range of artists and not necessarily just old masters inspire me, contemporary artists. We have, 20th century artists, like Austin Osman Spare on the booth as well because I've used his work, um, in mine. But old master drawings tends to be what I'm looking at and have been looking at for the last 10 or so years. And so there's works in the Gagosian stand here that refer to paintings by Guido Reni, Pompeo Batoni, Odilon Redon, Murillo.

Quite a range and usually more than one artist is referred to in a particular work. I bring things together and stitch them together to, to make, uh, my own particular idea of what, uh, one of my paintings is. But I, the line is very important and so when I'm looking at an old master drawing or a contemporary drawing, it's really that sense of the way every individual artist uses their hands and brains to make a mark on the surface of something.

And for instance, we have a beautiful drawing by Ann Churchill on the stand, and the intensity of her work is something that I've tried to draw into my own work. And then having a work by Gaetano Gandolfi on the stand as well, you'll see these beautiful sinuous lines in his work.

AG: So it's more the line than the brushstroke you're saying that?

GB: It used to be very much about the brushstroke and some of my paintings now do come from paintings, that is the source images, but I then turn it back into a drawing, or I take the old master drawing and turn it into a painting. So I'm almost turning the, the drawn marks on a painting into a painted marks, or rather they're artificially painted marks.

About 10 years ago, I changed my work, um, quite a bit. Previously I was dealing very much with making paintings after paintings, and the surface of them was very sheer and flat, and I kind of thought that it was very difficult as a viewer to understand how the work was made. And I wanted people to be able to look at them and go through that sense of narrative that you have when looking at a painting, of imagining the artist making the work.

So I've tried to open up that a little bit so you can see some of the workings of what's happening in the paintings. More so now than you did work I was making pre-2014.

AG: We will go back to your practice later, but let's stay a little bit more about sourcing images because you know, thanks to technologies, since the diet is the research of artist, also art historian actually change quite a bit.

How do you find the images to work with is always in the flesh or also digitally and through books or internet?

GB: All of them. I like seeing drawings actually in the flesh, or paintings in the flesh, more to the point. There's something you get from being standing in front of an actual work, especially with a painting, they reproduce so badly sometimes, be it on the computer screen or in a book.

And you don't get that sense of, as I said before, the narrative of the artist making the mark on the surface. You can't read it so well when you see it reproduced, and therefore seeing something in actuality is very important. But having said that, a source material for the work I'm making, websites have been very important.

So when museums like the Met in New York, or the Rijksmuseum developed wonderful, uh, websites, it opened up a whole new world because sort of rather dark and dusty areas of their collections were opened up for the first time for everybody to see in, in high resolution. Images of drawings especially that just didn't appear in books. And I have a huge library of books both on paintings and drawings and sculpture, that I refer to continuously. I always have books open in my studio when I'm working. And now the British Museum has a, their website is sort of overtaken many of the others because the resolution they have is wonderful. So I do look at websites quite a lot as well as books.

AG: Great. It's nice that you mentioned this effort that museum has been doing all around the world in digitalizing the collection, which is, I think is still a big revolution going on and is very important in our field. Thank you for saying something that I really believe, even a painting is still a three dimensional object, and you have to see that in the flesh, as you say, to understand its power.

Let’s speak about your painting, which is a kind of painterly appropriation. This word appropriation, you know, is very loaded today in this time we are living. Do you differentiate the use of historical reference from appropriation or is just appropriation the point?

GB: I mean, I realize when you put the word ‘cultural’ in front of appropriation, it takes on bad connotations, therefore, I tend not to use the word 'appropriation' anymore. During the 1990’s and 2000’s, I would call myself an 'appropriation artist' without thinking about it, but language changes and it's great it changes. One thing I was thinking about, especially when it came to doing this show here, is that three of the artists that I'm particularly obsessed with, belong to Dynasties in the sense that they were multi-generational.

The Gandolfi family, in Bologna, there were a number of, um, artists in the family that worked together. Aldo Gandolfi, Gaetano Gandolfi, and Mauro Gandolfi. And they all have slightly different styles you can tell which is doing which, just about. Some of them specialized in drawing, some more in painting, but they have a shared mannerist sensibility, and you can understand what they were learning from each other. So they were appropriating each other.

And again, Abraham Bloemaert, another artist who I love and have a very beautiful drawing of his on the stand in the booth. But again, that drawing, the understanding is that the drawing was taken by his son Frederik, and cut up and stuck back together. So he's taken drawings of trees and turned them into a little forest in woodland scene, and even stuck little figures in, all from his father's work. Although Frederik was an artist as well, painter and printmaker specifically. And again, sort of Frederik's mark making is slightly different, slightly tighter than his father's, but he was appropriating his father's work, uh, quite clearly.

And it's interesting that, is that appropriation? Is it cultural appropriation that one artist would learn from their father, or? So, I feel I'm just becoming part of the family in some sense. I'm trying to induce myself into sort of learning from the master and being subject to different artists.

AG: Yeah, you're totally right, the practice of the bottega, not the worship where many generation, many people at the same time and many generation through the decades, sometimes the centuries.

GB: And Tiepolo is another artist I've used as well. And I have drawings by Tiepolo, and that was a family again, which you could, you can tell the difference between them, but..

AG: You like family appropriation, you should check Bassano. You know, Jacopo Bassano started at the beginning of 16th century, and his bottega, his worship finished at the beginning of, uh, the 17th century, 1620. So for one century they were using the same database, a repository of images more and more and more. It is a little bit what you do, yourself.

GB: Yes.

AG: So you don't have a bottega, but you are your own bottega, let's say like that. Let's speak about, um, technique. You work often on smooth surfaces, and then with the kind of manipulation of the pictorial gesture that seems to imitate and sometimes to sabotage the original author.

Could you explain how work this process, I mean the choice of materials, the layering, the brush works, and uh, how this help to transform the historical image into something else?

GB: Well, as I said previously, I tend to use drawings as a starting point and very often, multiple drawings. And I'm looking at the mark making almost the subject of the work doesn't necessarily have to be so important because I can manipulate and change the subject, but that that's stylistic sensibility of the drawing.

For instance, there's a work on the stand here, which is the starting point was a drawing by Odilon Redon, uh, and I wanted to turn it into a painting, but I actually, um, found drawings by Guido Reni and Pompeo Batoni and have combined them to make a drawing, or painting rather, because it's, it's paint on panel, and, uh, it's called Living in the Sun, the painting. But it has the style and feel of an Odilon Redon. So that's why joining different artists together, picking the Glenn Brown aspect of their work, is very important. So I basically, I, I do use a computer sometimes to overlay images and play around with things digitally before I start. Not always.

And I'm also rather addicted to using the computer to be able to turn works back to front on. So when I get stuck with the painting, I take a photograph on my phone, put it on the computer, turn it back to front, and I can actually manipulate it on Photoshop and try things out and try glazes and lines and things on the computer just to see what might work, and then I go back to the painting.

I don't use that all the time. I'm not obsessed about it because I find it rather crude in the end. I would never want to make a painting where the end product was sort of computer generated, printed or whatever, because you make mistakes when you’re painting, and those mistakes can be awful sometimes, but they can be really great other times, and it's that jeopardy you always go through. Every time you put a mark on a painting, and you can't take it off, you are running the risk of destroying the painting. But that's what makes it exciting to paint.

AG: So you plan in advance what you are doing, you study what you're going to do, but there is always something unpredictable right in, in what you do? Do you like this?

GB: Oh yes. Lots unpredictable. And sometimes a painting just isn't working, and then I'll actually start drawing or painting another painting, sort of part covering over elements that maybe don't work and things can change enormously in the process of making a painting. And to that end, some of the paintings I've been working on for 10 years just because they haven't quite got resolved. And then I'll come up with a radical idea for resolving it, and then, well.. So hopefully it'll get finished at some point. I hate giving up on a painting. I just want to, yeah.

AG: A little bit like, in the workshop of the artist of the past, they were always reusing the canvases. Let's go back to you, to your work. Your titles are very, very special. Often, they don't directly describe the works themself. There is a kind of dissonance between the text and the image. Would you say that your title, they serve as a kind of parallel narrative as another layer of the meaning that of your works? And, uh, how do you see the relationship between image and language in your work?

GB: Um, I have to go absolutely back to Duchamp here and his famous quote that the title of a work is like adding an invisible colour to it. It's exactly what I'm trying to do. And to that extent, the poetry of the words combined with the image are absolutely important. And I'm not trying to add a narrative to the painting. I'm not trying to embellish what's already there. I'm always, I'm, that's not strictly true, I'm trying to oomph, the whole idea of the painting up to, to really make it stronger I should say, the idea of what the painting's about.

So I mentioned before a painting called Living in the Sun, but it's a very dark painting. There's a, a track by Joy Division called Transmission, and in the first lines of the song, it says we could have a fine time living in the night. And that came into my head when I was making the work, but I didn't want to call it sort of Living in The Night because it's too literal. It's two heads, one's looking up, one's looking down, and there's water in front, and it's all just made from black lines and black glazes and, it's too literal. So, and then this idea of the sun, living in the sun came about, which is the opposite to what the painting looks like in many ways. And my brain went to those images you see of the sun, the magnetic fields of the sun causes lines to come out, to escape. Plasma escapes from the sun and then gets pulled back down by gravitational forces into the sun and that for many years, that's what I do been doing in my paintings. I have lines coming up and curving around, and then the gravitational force of the image brings it back down into the centre of the painting. It's a way of controlling your eye as it moves around the painting. I like that sense that gravity is very similar to the composition of a painting. That you basically want to bring the person back to the middle, but you also want them, their eye to fly around different parts of the painting as well.

So again, the, the lines in the painting looked like the surface of the sun as well. So the title, Living In The Sun, to me, made sense. But you just have to think about it a little longer. And there's a, another painting, which is actually based on the same images, Guido Reni and Pompeo Batoni, called That’s Saint Joan Doing A Cool, Cool Jerk. It's a very peculiar title. It comes from a song by This Mortal Coil, that was a cover as well. So they appropriated another artist who, I forget who actually originally wrote the song in 1970's folk group. And I heard the lines of this when I was making the painting, and I was just intrigued. First of all, my painting is predominantly green, and so the idea of fire, and it's a child and a female head, and they have quite bright lips. And Christian iconography is very important to the work I make. Um, and so when the title says, That’s Saint Joan Doing A Cool, Cool Jerk, well, you think. Well, what do you think of Joan and being burnt at the stake? Is sort of obvious. And when you look at the mark making and the painting, you think of flames and fire, but then doing the cool, cool jerk you think, ‘what's that about? Why is she?’ and then, then it becomes rather the macabre because 'cool' can be taken in two ways, it's either, you know, something's really cool and good, or it's cool and cold. So you think of St. Joan and you don't think of cold, you think of fire. So bringing in the idea of St. Joan being cool when she's suffering, but in flames whilst looking at my painting. That's what I was trying to do.

So it's a very complicated colour I'm trying to bring to the painting. There is meaning to it, but you have to dig in order to get to it, and you'll find that with all of the paintings, really. Probably overly complicated, aren't they?

AG: It's great that everything is mixed up, contemporary culture, like you said, Joy Division, et cetera, with Old Master and also this kind of jokes is I think is very fascinating. It is complex, especially for a non-speaking native..

GB: I’m not expecting everybody to get all the meanings out of everything. I think you just have to enjoy the poetry of the words sometimes.

AG: To the fair, we are at Frieze Masters, as you all know. We just mentioned that you're also a collector. Okay. How do you choose something you want to buy? What drives you to this, uh, you know, desire of, of buying?

GB: Um, well first of all, I don't particularly like the idea of calling myself a collector. That to me, in my mind, that brings this idea of wanting to own things because, I want to possess them, and I don't really actually need to own them. I see myself more as a curator, because the reason I want to buy something is because I want to be able to show it to other people. The collection's expanded enormously since we had opened the collection in Marylebone here in London. And we try to buy things, this is Edgar, my husband and I, we try to buy things that talk to each other. Create a sense of conversation that have a sense of mark making in them, which is exciting.

They generally are images which are useful to me, which I have often have works in my studio. I always have a Hendrick Goltzius uh, work in the studio because it just tells me you are never quite good enough. You will have to keep going. There's an obsessive delicacy, which you will never, ever achieve in your life, and Goltzius had it and spade loads and, but, well, there's an artist like Annie French, for instance, whose work I absolutely adore, sort of late 19th century. And again, the intensity of her mark making pushes me to want to make sort of stronger and better and more intense and more delicate and compositionally more engaging works.

So I buy things absolutely to learn from them. Having the actual work there in my studio is completely different from having a book. I mean, a book's brilliant, I love books. I mean, I love learning about artists as well, and the context in which the work was made. But having a, a print, or a drawing, or painting in the studio, to actually inspire that, it, it brings out the competitive edge in me, fundamentally. I sort of, I'm trying to compete with a lot of these artists, and I buy things to push me further and to help create a narrative.

AG: Is there a painting that you really would like to have to have in front of you in your studio while you paint something? You know, I mean a masterpiece from museums or some collection, is there is any dream or as a curator, collector, painter as you are?

GB: I was asked that question, which, which piece of art from a museum would I like to own? And my immediate response, I was asked that recently, and my immediate response was, I don't want to own it, I want it kept in the museum where people can see it. Um, the idea of it being closed away in my studio would be awful. To, to bring the Mona Lisa into my studio and not allow people to see it, that would give me no joy whatsoever. I sort of love the massive queues that form. I wish people who can actually see it, but that's a different point.

But having a sort of Raphael painting and, and again, when you see reproduction of his paintings, you can't quite understand what makes them quite so beautiful. But when you see that delicate way that the layers of paint create this sense of flesh, for instance, or create this sense of velvet fabric, um, it's, again, that brings out the competitive edge.

There's so many paintings I would love to have, um, uh, endless, that I could learn from. And I would love to be able to paint in the National Gallery, for instance, to, to be able to really walk around and literally paint next to some of the paintings. I mean, I know you can get permission to do that, but.

AG: You can do it, yeah.

GB: I'm not sure it would work every day for me, right? To, to be able to look at things in the flesh there, there's nothing more exciting and there's no better way of learning how to be an artist.

AG: Actually we mentioned your public space or your Brown collection, which is open to the public. So actually this masterpiece would not be just for you because you just open a space actually to share your art with people. So what pushed you to do that? What was the driving force behind this, this choice?

GB: There's no great single reason for doing it other than I realized that I've always done it. I mean, especially being somewhere like Goldsmiths in the 1990s where we all put on exhibitions, you know, because the commercial gallery world didn't really exist. And therefore, sort of Abigail Lane who's sat here has, has organized many and Gillian Wearing, we've, we've always sat put on our own exhibitions because we had to.

And it was great fun and we'd made make work to show it to other artists to show it to each other. And we learned, you know, by discussion how to be artists. And I think that was a fantastic thing and I just want to keep that going, fundamentally. And we have a talks program in the space as well, and we show films, and we have even life drawing classes.

I can think, I just want to continuously be at art school, really. I sort of, I like that process and want to keep it going because, uh, learning is such an enjoyable thing to do. And I don't necessarily see myself as being the teacher all the time, I see myself as being the student as well, so. But at some point you have to grow up and be a bit of a tutor as well and, yeah, and mix things up.

AG: And do you like to teach? Having pupils is something that you, you would do?

GB: For times I have taught, um, I really enjoy it and it, it teaches you to be humble because you encounter artists who have skills and techniques and abilities and conversations with the world, which you will never have.

And, one of the things that Michael Craig Martin, who is one of my teachers, made very clear to me. He said, you know, “everybody has something interesting to say”, and it's absolutely true. Of all of the hundreds of artists and students I've talked to, I've never encountered anybody who didn't have something really interesting to say.

Even if that was that they're bored, that they don’t know what to say. You realize they have a very particular way of telling you that they're bored and don't know what to do, which is fascinating, and you can help them bring that sense of desperation out. And that they have a particular take on the world, and I want to know what it is. And it doesn't matter what their background is, it doesn't matter whether they come from a council estate in Peckham or went to public school, everybody has an individual statement. And seeing the world through somebody else's eyes is one of the most beautiful things that we have.

It's why we watch films. It's why we read books. It's why we look at paintings, to look at the world through somebody else's eyes and realize how strange it is, how refreshing it is to see the world afresh, and it makes us feel sort of young again to do that as well. So, yeah.

AG: For sure you have a lot of interesting things to say. I think we all agree about that. Unfortunately, the time is very limited and, uh, I would like to have few minutes for some questions because I'm sure some of you wants to speak with Glenn.

Question 1: Mr. Brown, when I look at your, uh, paintings and your work, I'm really amazed about the control of the line. You’ve talked about it earlier in the beginning of the talk. I'm just wondering, could you tell a little bit about how you trained, the coordination with your eyes and with your hands, and how much effort and training you put into that to get the kind of line that you want? And is it something similar, like a tennis player also has to work on this hand eye coordination or table tennis player to really get it, uh, to get it right?

AG: That could be another interesting addition to your practice. Huh? Think about that.

GB: Tennis. Yes. That's, uh, was it, how many hours do you supposed to, 10,000 hours, is it, that you're supposed to spend on something before you learn how to do it properly? Yeah, I’ll never get that good at tennis, definitely. But, how important is hand eye coordination? Well, artist like Roger Hilton who had mobility problems later on in life. He couldn't move his arms very easily, and in some sense that's when his drawings became the most interesting because you can see that fight in every mark that he was making, and it brings a beautiful energy into his line making.

So an artist doesn't necessarily have to have elegant and entertaining lines. They don't have to be Novak Djokovic of the line making, in order to, to be wonderful at it, you can have problems in mobility and still produce amazing lines. Again, it's about allowing your personality to come out in your mark making. And physicality is very important. I mean, I think when you make a line on a tiny bit of paper or a huge painting, your body comes into it. It tells you the story of what kind of person you are by how you make those gestures, be they big or small. We have a, another artist in show in the space, he was in prison for a long time in Russia. You can see that sense of desperation, of suffocation in his marks. He makes these tiny little marks that are just twisted and turned, and these rather surrealist scenes, fantasy scenes have all built up out these, these tiny little pent up, angry marks, thousands and thousands of them. And it's wonderful to see that completely tight, annoyed gesture and how it traits this beautiful image. So there's, yeah, you don't have to be learned to be perfect, you just have to learn to be yourself. Again, everybody has their own individual way of working, and it's that sense of individuality, which you want to see in a painting or drawing or sculpture.

Question 3: Um, yes. I was just wondering if you could perhaps, uh, say a little bit more about, um, these kind of parallels, uh, between different works that we've seen in the booth, for instance, or, or even in, in the space and at, at your collection. I mean, is it partly because you admire these other artists work that you try and perhaps, emulate or, you were talking earlier about competition, but is it always that, or is there another side to it? Because sometimes it's recognizable, sometimes less.

GB: I'm, I'm deeply jealous of lots of artists. I mean, I mentioned Hendrick Goltzius before, and the sort of, the genius he had. He was again, showing off in, in these were works, prints predominantly, but he was also a painter and draughtsman as well, working in the 16th to 17th century. And the sense of detail he has, he's basically showing off that he had magnifying glasses, that he could make work, which was so detailed, which needed very high technology only only available in Northern Europe at the time. Nowhere else could achieve magnifying lenses detailed enough for him to be allowed to make such detailed work.

And artists like Jan Müller working at the same time as well, um, were creating work, which was absolutely extraordinary. And I look at their work and yes, I want to be a bit competitive, as competitive as I possibly can be to it, and there's nothing wrong with it. Competitive is another word for language. You know, somebody else uses the word and you copy that word and use it yourself, and that's not appropriation, it's just a shared language. And that's one of the beauty about shared languages, be it language of image or the spoken word, the written word, music. We have ways of borrowing things from each other to create new languages, and that's what I'm trying to do. I'm just going a little bit further back into the past sometimes then a lot of people would necessarily go in order to cull new words or languages, turn things around.

Uh, for instance, we're showing a work by Hendrick Goltzius, an engraving by him, and there's a tail on the back of the horse and the exquisite way in which that tail is drawn, which is with these curved, tightly energetic marks. And I've taken aspects of the tail in that horse and used it in my paintings, very deliberately, just because I love that sort of pent up energy in it. It's almost like a nuclear reaction in a horse's tail. It has that much energy. And he loves buttocks as well. And who, be it, a horse buttock, a woman's buttock, or a man's buttock, who, who can not like a bum like that, ey?

AG: That's the, the best way to close this conversation. Okay. Thank you very much for being here today. Thank you, Glenn. It was amazing to hear you speaking.

GB: Thank you.

ET: Thank you for listening to the Frieze Masters podcast. Next time, Antony Gormley and Arturo Galansino discuss sculpture’s potential to reconnect us with our bodies and the world around us.

“For a very very long time, the statue has been at the service of, if you like, hierarchies of power. How can we make it intimate again? How can we make it about feeling? How can we make it about, in a way, collective futures, rather than particularly powerful individuals?”

The Frieze Masters talks programme and podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with Dunhill. The Frieze Masters podcast is a Reduced Listening production.

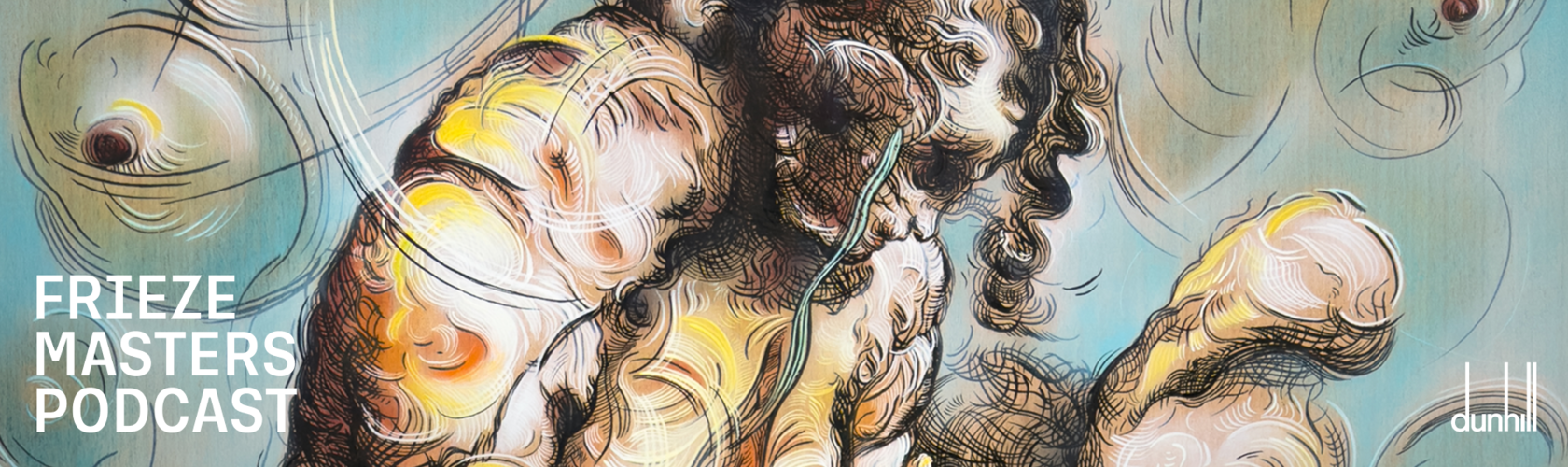

Main image: Glenn Brown, Rabbit Hole, 2025. Acrylic and India ink on panel, 30 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.6 cm). Framed: 40 x 29 3/4 x 2 inches (101.4 x 75.4 x 5 cm © Glenn Brown, Photo: The Brown Collection, Courtesy the artist and Gagosian