Frieze Masters Podcast 2025, Episode 7: Sculpting as a New Humanism

The seventh and final episode with Antony Gormley is presented in collaboration with dunhill

The seventh and final episode with Antony Gormley is presented in collaboration with dunhill

‘The way that sculpture draws us into palpable physical experience is so important. Sculpture is not a picture. It’s a thing.’ – Antony Gormley

In the final episode of the 2025 Frieze Masters Podcast, artist Antony Gormley and curator Arturo Galansino discuss how sculpture can help us reconnect with our bodies and the world around us. Gormley asks, ‘how can we make it about feeling and collective futures – rather than particularly powerful individuals?’ ‘How can we make it intimate again?’

Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and the Frieze Masters Podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with dunhill.

About the speakers

Sir Antony Gormley CH OBE RA is a British sculptor. His works include the Angel of the North (1998), a public sculpture in Gateshead, UK. He is joined by Arturo Galansino, art historian, curator, director general of the Palazzo Strozzi Foundation in Florence and this year’s curator of the Frieze Masters Talks programme.

About the Frieze Masters Podcast

The Frieze Masters Podcast is back for 2025, bringing you seven conversations across art history curated by Arturo Galansino.

Entitled ‘Woven Histories’ and recorded live at Frieze Masters 2025, this year’s series features artists, curators and thinkers, whose conversations weave together geographies and chronologies, and challenge us to look at history in new and unexpected ways.

Topics range from the evolving relationship between fashion and art to the role of the archive in Black history, the last Mughals and their cultural influence in India and the enduring inspiration of the old masters and renaissance art on contemporary making. Speakers include artists Tracey Emin, Glenn Brown and Antony Gormley, museum directors and curators Nicholas Cullinan, Émilie Hammen, Elizabeth Way and Carl Strehlke, and writers Edward George, Matthew Harle, Christopher Rothko and William Dalrymple.

Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

The Frieze Masters Talks programme and the Frieze Masters Podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with dunhill.

Transcript and Images of Works Discussed

Emanuela Tarizzo: Welcome to series four of the Frieze Masters Podcast, brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with Dunhill. I’m Emanuela Tarizzo, Director of Frieze Masters, and this podcast brings you our collection of talks from this year’s Frieze Masters fair.

In this episode Arturo is joined by Sculptor Antony Gormley for an insightful conversation that asks ‘in an increasingly digitised and insular world, how can sculpture help us to reconnect with our bodies and the world around us?’

During the talk our speaker shared images of artworks with the live audience. Please visit the Frieze website, linked in the show notes below, to see the images they referenced.

And now over to Arturo to introduce this week’s talk.

Arturo Galansino: Today we speak with one of the most important living Sculptors, Antony Gormley. And the title of our talk is Sculpting a New Humanism, which really relates with the spirit of Frieze Masters because we want to put in touch and in connection different eras. Antony’s work relates to Renaissance, and Humanist values, of course he brought them to the future. With Antony we are going to discuss about sculpture, about his practice and technique, about his profound relationship with the languages of the past, and about his spirituality and his connection with the Eastern World.

Arturo Galasino: Welcome ladies and gentlemen. Full house. It's the last one of our Frieze Masters. Wow, I'm so sad, it was so fun but I'm happy to finish with Antony. You are considered one of the most important living Sculptors, and you recently published a book about sculpture. The title was Shaping the World, right? What does Sculpture means to you?

Antony Gormley: Good question. I think that question, what is sculpture good for is particularly relevant now as we move into this cyber age where so much of our time is kind of pulled into information that comes through screens. The way that sculpture draws us into firsthand palpable physical experience is so important. Sculpture is not a picture. It's a thing, in a world of things that refuses in a way to play the game of functional things in the world and allows us, I think, to ground ourself in being, and being situated in a place. I think that a standing stone for me is the, "oah" nature of sculpture. Why? Because it identifies a place and calls upon our time, and asks us to reorientate ourselves in the greater than human world.

Arturo Galansino: Let's go back to the context where we are, no? Frieze Masters. This fair is about connecting different eras, different epochs from the prehistoric time to modern art. We often spoken about the body as a measure, right? And this, uh, is really linked with the Renaissance tradition, with the human figure was seen as the centre of the cosmos. How might a new humanism look to you today? And can sculpture help us imagine it?

Antony Gormley: I really think it can. I don't know about a new humanism. I think that the challenge that our species faces generally is ‘how do we reintegrate our lives with the biosphere?’ You know, Alberti and Vitruvius identify in a way, a time where imperial measure or ‘the body of man’ was used as a measure of all things with the assumption that somehow we were the masters of the universe.

I think it's impossible to feel that now, where either directly or indirectly, I think that everyone understands that our present life form is toxic to all other life forms. So for me I think the urgency of sculpture in bringing us back to being situated, is to treat the body as a place that is continuous with all other places. That means that there is a continuum of space. There is, as it were, the body itself is the space. And, for me, that realisation of the body, not as an object to be idealised and seen as at a distance and made into a statue. I think that my work, while looking like a statue, has nothing to do with statues, but I want to think again about what is a human space in space. Less about portraiture, less about idealisation, less about narrative than about a question. And I think the way that two questions ‘what is a sculpture?’ and ‘what is a human being?’ can come together. And I guess for me, sculpture as a form of physical skepsis, in other words, investigating, probing our condition, is maybe the best work that it can do, because it’s at no longer the service of power. It's no longer trying to, in a way, reinforce, uh, the already known systems. It can be a probe into asking new questions about how we fit in a wider world.

Arturo Galansino: Let's stay on this, uh, word so meaningful for your practice ‘body’, right? Your work often move between single figures and vast fields of bodies. How should we interpret this shift in relation to the ideas of being individuality and collectivity?

Antony Gormley: I'm quite suspicious of the idea of the universal or the generic. So I have tried in my work to acknowledge the fact that it comes from a particular body, a capturing of a human moment of lived time. That is then described at first for the first 20 years of my work as a empty body case. I call them ‘body cases’, that have the invitation for you to, in a way, empathically inhabit those.

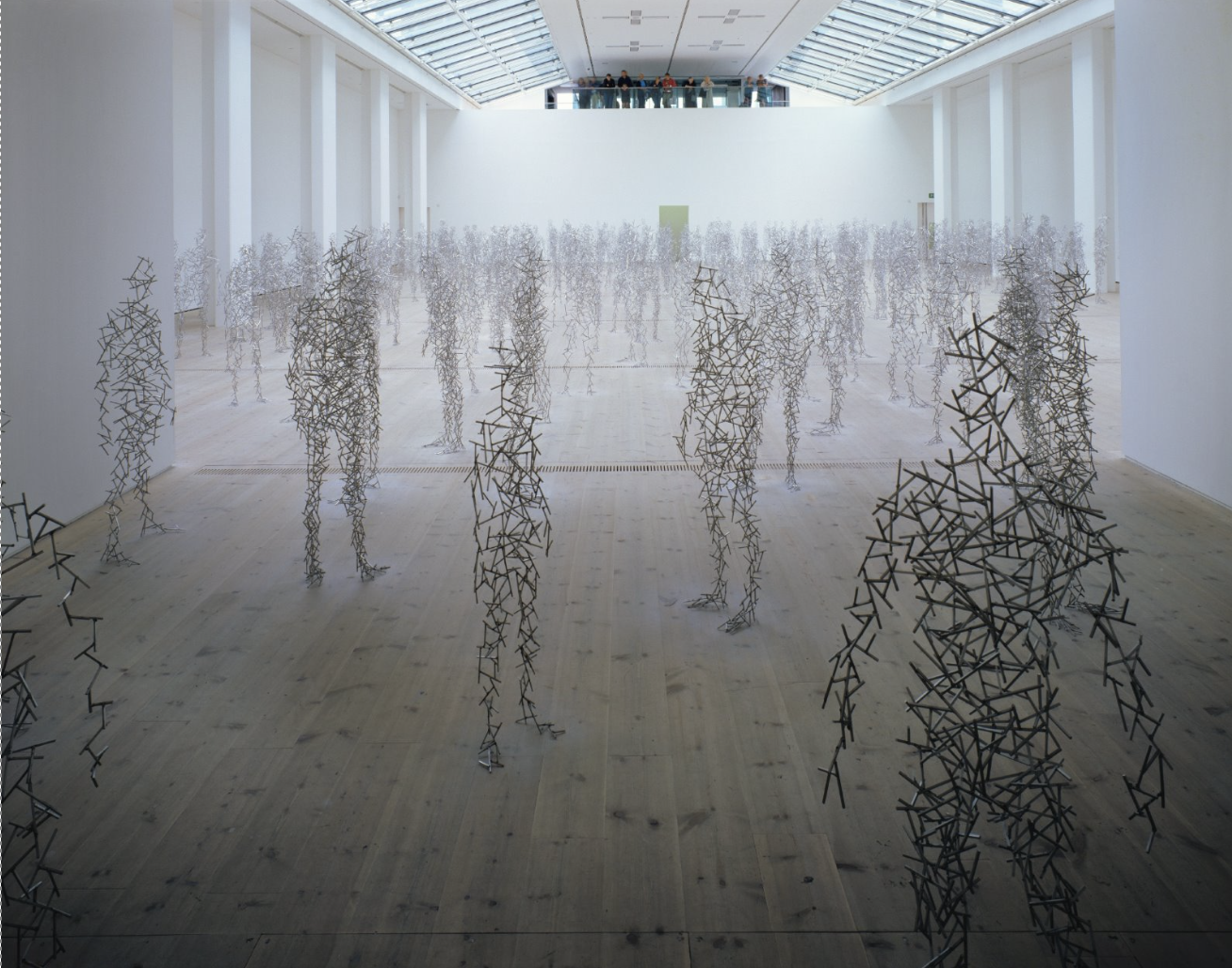

And then more recently, thinking about how I might describe the body less as a thing and more as a place of transformation. So an energy field, and you can see that in, uh, Domain Field where we have nearly 300 bodies that are now not my body, but actually the body of a community that has been made into, as it were, this open field that you are invited to walk through and between. And yeah, for me it was very important to break the idea of the singular object, and right from the very beginning. So, the second of the three-part body works where I was really exploring ‘how can I bring the body back into art in a way that is really different to that long history of the way that sculpture has been used?’

Anyway, if you think of those enormous statues of Ramses II or Hypnosis III, you know, for a very, very long time, the statue has been at the service of, if you like, hierarchies of power. How can we make it intimate again? How can we make it about feeling, how can we make it about in, in a way, collective futures rather than particularly powerful individuals? And for me, this breaking of the aura of the unique and turning the singular into the multiple, you could say that three is the beginning of infinity, was really, really important.

And that word ‘field’ is very important to me. I think it opens up this idea of energy fields, but also fields that are the location of potential. And maybe I got the idea of that from particularly the sculpture of America of the late sixties and early seventies. Going to see The Lightning Field, another field, of Walter de Maria was just such an extraordinary, for me, opening up of exactly this from unity to multiplicity, from the singular to the field where a high plateau, uh, in New Mexico was literally filled with these needles that described an absolutely flat plane at their tops, but came out of a very undulating, high chaparral, uh, landscape. And we were given a bottle of water and told to go out into it. And that experience has stayed with me since 1979 when I did it. That through, as it were, this turning sculpture into a place of proprioception where we are invited to look not only at where we are with alertness, aliveness and attention, but also at ourselves that actually the reflexivity of sculpture, the potential reflexivity of sculpture suddenly turns it inside out. And through sculpture we are invited to think about how we feel, about how the gravity is allowing the weight of the earth to press up against the weight of our bodies.

Arturo Galansino: Let's stay more with the methods of the sculpture, the practice really, the technicality of your work, because sculpture has always been considered one of the most demanding arts, you know, because you need to master the methods, to control the materials. And over the year apart, your very early attempts with lead, right? And recently also with wood, by the way. But you, you have always been working mainly with iron. Could you tell us something about your relationship with iron and its technique?

Antony Gormley: Yeah. It's really important to me to use materials that are of our time, and I feel that bronze and marble both come freighted with their amazing history in the making particularly of statues. And I wanted to use a material that is absolutely associated with the Industrial Revolution. But at the same time, because of how it oxidises, how, how its surface becomes rich and actually changes in time, it expresses something about its relationship with the Earth. 85% of the core of this planet is iron. If you would take the totality of the mass of the earth, it's about 35%. Iron is what gives this planet its magnetic field, it's what gives it its density, it's what keeps it on its trajectory through space. And you feel it, you feel it when you come to a mass of iron. And at certain point, I, I reversed my process and instead of making empty cases, I began making solid masses in human form. I think you feel that mass, the nearly 700 kilos of solid iron that has basically replaced the space within the mould. I think that through it you are invited to, yeah, recognise your own mass. And through its stillness and through its silence, you are invited to move, to move around it to see how it fits in, as it were, the context, in the umwelt that it finds itself. Iron, for me is a way of reestablishing the physicality of a sculpture.

Arturo Galansino: How have the technologies involving your work evolved in the last decades? Has your practice itself changed recently as a result?

Anthony Gormley: It's interesting because we moved studios from Peckham, to just north of King's Cross. So we moved in around 2001, 2002, and I built this studio as a purpose-built studio, with David Chipperfield, wonderful architect. And it's interesting that up to that time, all of the body work was made by moulding me. So Vicken, my wife is here, who, yeah, was my first and closest assistant who, you know, it was a almost daily ritual that I would have to stand or lie or sit for up to two hours, be covered in plaster and then cut out, and then we would use those moulds, um, as the basis for works like Land Sea and Air.

The moulds were strengthened with fiberglass, and then lead was beaten in sheets over the top. And anyway, at that moment of moving from Peckham to King's Cross, there was also the desire to begin now to think about our time. And I think I wasn't aware at the time how obvious this was, but I began to fill the interior void of the moulds with blocks. And now I'm, I'm, I'm clear that these, this was a necessary physicalisation of the pixel, which I think really determines our cyber age. And, at the same time, you know, when we first moved into that studio that we had maybe three computers and they were mainly used for doing the accounts or kind of writing letters. But I'm now joined, you know, there were maybe five of us when we moved into that studio. There are now 30 of us in that studio and another 30 in the studio in Hexham where this foundry, that has now become the compliment in a way.

In London, we work in and with computing, but we are always pulling, as it were, the, the, the advances that three-dimensional design gives us out from the screen into three dimensions. So the studio's full, full, full of models and I suppose to really answer your question, I think we have embraced the potential of 3D modelling in digital technology. I did do three new, uh, body moulds and I realise quite how tough those first 20 years was because it was quite difficult, but on the whole now all of that moulding is done by scanning. So I'm naked, I stand, we have a digital scanner and what used to take two or three hours now takes maybe a minute. And what we have then is a registration in between 30 and, and 120 thousand points of over the body, which then we can use, as it were, the matrix out of which we then derive a body sculpture.

Arturo Galansino: Thanks to the technology Vicken has less work to do, so I think.

Antony Gormley: Yeah. But she's gone back to making her own beautiful work. We have my drawing studio and Vicken's painting studio right next to each other. Whenever I want to calm down because things are getting out of control, I have to go and sit with her and the smell of turpentine and, uh, everything is calm in there.

Arturo Galansino: From technology, let's go to the nature. Your works often inhabit public landscapes. How do your sculptures and installations interact with nature?

Antony Gormley: Well, I think I started with that with the stone of Stenness. I think this is the power that sculpture has. Which curiously, in the 20th century, it lost. Once in a way, art becomes commodified and institutionalised and is seen as being, in a way, a free object that, that can be offered for exchange. It loses one of its most powerful potentials, which is to instantiate place. And you can test this as a mind experiment. Think of all the places that you can't forget because of the sculpture that is there, or think of the sculptures that you can't forget because of the landscape that they activate.

There's a curious economy that started maybe in the 1820s, but the ability of art to free itself from service to power was paid for by its withdrawal from collective space. And I feel that's a massive loss. It's a loss for art, but it's also a loss for the world because if we have had to make things, particularly models of ourselves, in order to understand ourselves, they can only work if they are situated. We've got so used to, in a way, these free objects that can kind of move around. And I try when I'm making a show to make them resonate with their context. But the greatest way that a sculpture can live is to be literally rooted in place. And, and yeah, for me, I say this a lot, but I, I want to use the time that is left to me to make works that are, as it were in place, that do that job of concentrating in a way, a collective life in a singular object.

You might say this is entirely pre-modern. I'm talking the language of totems, you know? And I think, I think of the Angel of the North as being a good example of that.

This is my first drawing of a project that we are in the middle of. It will be 110 meters long, 23 meters high, about 18 meters deep, on a beach in South Korea, in Shinan province. And this is a work that is the offering of our human species back to the elements at a time when we know we are living in massive climate emergency, massive climate breakdown. This will be a measure, as it were of sea rise. At the moment, at high tide the work will, uh, be about 1.7 meter below the surface of the sea. By the end of the century, it could be anything, uh, three meters or above. I guess, you know, for me this is a continuation. I mean, I'm very, very humbled that this, you could say, relatively undeveloped part of Korea, which is otherwise extremely developed, has decided to make this work. And when I say developed, I just mean that it's not a rich county, not a rich province. But somehow they felt that it was really important at this time and in that place to make a work that expressed the life of the community, which is just so different to the metropolitan lives that most of us live.

They make salt by, you know, bringing in the seawater and allowing it to evaporate by sun and wind. They grow rice, they grow spinach. It's a community very dispersed that is very, very close to the conditions in which they find themselves. And I, I feel that this sculpture in some ways celebrates that, and that situatedness, but also brings it to mind to the rest of us.

So, I mean, for me, I am always amazed that our forgotten ancestors were able to expend so much collective energy. If you think of the, of the nine like lines of stones in Carnac in Brittany. Stones that weigh from four to 160 tons that were prized from the surface of the earth stood upright and made into these alignement. This was a collective, creative work that worked with the landscape, that made in a way, a place into a place of imagination. And invited everyone in that place to relink their lives, to not just the immediate, but to the greater than human world. And that meant the stars, that meant the seasons, that meant, uh, the conditions of nature around them. And that's what sculpture can do. It's a still and silent thing that allows all of the changes around it to become apparent, felt, attended to.

Arturo Galansino: In the last year, this has been a recurring concern for museum galleries, let's say, for the global art world at large. Uh, the issue of environmental stability. How do you address this challenge in your own practice, in your own work, in your own studio, daily?

Antony Gormley: I think, you know, the fact is that the art world generally is profligate in its carbon footprint. I realised that I'm embedded in it and I do what I can. In terms of the making of the iron works, 90% of the work that I make is recycled. And we start with brake shoes. Brake shoes are also cast iron, the right relationship of molybdenum, titanium, vanadium, and nickel that allows us to turn them back into basic cast iron. Also, what I've just done and is still on at the Bukhara Biennale. So this is, uh, 300 tons of clay, just simply taken out of the earth, mixed with the same volume of straw. Hand, oh no sorry, foot manipulated for three days until the straw begins to ferment. This is a absolutely ancient technique out of which both Samarkand, Pukara, and Tashkan, were made, and I just work with local artisans. So, I'm lucky enough now to have worked twice with Diana Campbell, who recognised in a way the limitations, and particularly the carbon footprint of large Biennales and art fairs like this, and said, “look, we'd like you to come, but don't bring anything. Come and see what's already here. See how materials and methodologies have grown in this particular area, and see if you can work with them.” And that was such a liberation, and such an obvious idea that, that if art, in a way, is an open, creative space of potential collaboration, learning, and the exchange of thoughts and ways of being.

Anyway, that's my answer. I think that, you could say, the model that Richard Long pioneered, you know, in 1962/3, A Line Made by Walking, A Line in The Himalayas, something just transformed by minor displacement or human activity that then allows us to think in and with that place, even without having to go there. So yeah, the commodification of art and its exchange value overtaking its social, spiritual, and physical potential is a problem. And I think this is a good place to think about it.

Arturo Galansino: Okay, so let's stay in this place. This fair is also about connecting different cultures, different region of, of the world. You have been speaking about recent experiences in Asia or Korea to Bukhara. You're very excited about this Korean project. But this is a long relationship because you started travelling in India, especially when you were, when you were very young, right? Can you tell us how Eastern philosophies and religions nourished your own spirituality and, uh, mainly about your relationship with this part of the world in general?

Antony Gormley: I mean, I, I wasn't alone, you know, everybody was on the hippie trail and I was a good hippie. Uh, so aged, yeah, aged 18, all I wanted to do was go to India and I managed to do it in my first long vacation at Cambridge. And got to Kathmandu, I hitchhiked all the way to Istanbul and then took local transport from that point onwards.

And, I mean I suppose it was a dual inspiration. I mean, everybody was, I think, at that time reading Alan Watts and looking towards the East for alternative ways of thinking, being, and it was a time when both Princeton and that wonderful bookshop Watkins, down the Charing Cross Road, were beginning to make available translations like The Thousand Songs of Milarepa, translated by Evan Vines. The Secret of the Golden Flower, The daodejing of Laozi uh, the etching we used regularly, we all had our yarrow sticks, or our coins, and would nearly every day you would kind of use that extraordinary oracle in which the Hexagrams use the references to elemental nature. The, the relationship between water, air, earth, to guide in a way, human action.

And the things that I intuited from books, whether that was, you know, reading Leadbeater and Besant’s Thought Forms, or Gurdjieff or, Alexandra David-Neel, finally, I arrived at joining a Monastery Sonada run by Rinpoche in the Eastern Himalayas. And at the same time, uh, taking teachings from S.N. Goenka in the Vipassanā. And this was the complete reversal of the knowledge value system that I had been brought up in. I had a very classic upbringing and a classic education, and suddenly I was given the tools of understanding that actually you could use, as it were, attention and intelligence to examine your own condition directly. I did 10, 10 day courses, uh, with Goenka, which was usually three days of Anapana. That's awareness of breathing, followed by seven days of Vipassanā, which is awareness of sensation.

And this really connected with a very early experience of, of mine where I was sent up after lunch as a young boy, for a rest that I didn't feel I needed, but being a good Catholic boy, I was gonna do what I was told. And would lie flat and close my eyes and be in this claustrophobic red immediate space. Because I was always sent up to this enclosed balcony that was terribly, terribly light, and it had a cork floor that you could smell the kind of the, the, the glue that had stuck the tiles to the floor. Anyway, it was not the easiest place to go to sleep, but it was, it was really extraordinary, this experience, which was very vivid, of being in this red, hot, tiny space behind my eyes, and over time feeling it transform into something darker, deeper, bluer, until I was floating in a space without objects, without edge, that seemed to have this potential of infinite extension.

And it's curious that I find myself a sculptor now, but that's the means that I want to make that realisation that actually was reinforced by my meditation and my meditation practice that continues. That actually inside each and every one of us is this infinity, this sublime, that isn't an idea, it can be immediately and directly experienced. And I think that, that entry into an invitation to the, I suppose, palpable experience of, you could say, the void, of Śūnyata. That's the Pāli word for it. Changed my life and, and I think everything that I have made since is an attempt to either bear witness to it or provide an instrument for others to maybe sense it.

So Passage, which is maybe the most obvious proprioceptive instrument that I've made, which is a 12 meter long passage in human form that you walk into and you are walking into the dark because you are walking into your own shadow. And some people never make it to the end because acoustically, it's very alive, so you hear the foot fall as you are walking. But then at a certain point you turn around and you are released back towards the light, and back into the world. And maybe it's too much to ask, but I think of all of the early work, my encasement in plaster mould and then release, is a kind of rebirthing process. And maybe it's too much to think that the sculpture can do that, but that's what my ambition is, that in some way these objects are nothing about making a picture of something that already exists, but about trying to be a reflexive instrument by which people that are attending to it can feel their own aliveness, their own being. And maybe that's too much to hope, but I think that is what the potential of sculpture, that it confronts us with our own existence.

Arturo Galansino: Thank you, Antony. Inside us, you said there is infinity, but unfortunately our time here is very limited.

Antony Gormley: But can we have some questions?

Question 1: Can I just ask, in 2007 at the Hayward Gallery, you did Blinding Light. How does that sit with the spirituality in, in your practice?

Antony Gormley: Um, I think that this was an instrument of a direct experience of non-duality. For me, the Advaitan tradition, the Shaivite tradition, says that the world as we see it is maya. It's all appearances, it's illusion. And that we live as it were in a collective mind, that all consciousness is distributed. So, for me, maybe this was a clumsy instrument, but I'll, I'll describe the room. It's about twelve meters by nine with a doorway. It's a room made of glass. The doorway is permanently open. Inside it is a rain cloud, 10 times the density of an ordinary rain cloud that we might find in the upper atmosphere. You pass through the threshold and if you have your hand in front of you because you are going into, in a way, invisibility. You, you, you can't see your hand, but you are aware of the acoustic environment, so you're going to hear the splashing of people's feet because the cloud is creating rain. And you might walk and then somebody becomes visible at about 200 millimetres, and you can't help but laugh the minute you see, see somebody, uh, appearing out of a manifest light that is materialised through the cloud. It's like you are meeting somebody in a very different environment.

Anyway, people have reacted in many different ways. “Now I know what it'll be like to be dead” or “now I know that I don't need a body”. My ambition there was, yeah, to make this chamber that would allow us to experience, you could say, losing our body at the same time, being in it in a way that would be impossible without that condition.

And people would say, “what did you put in that cloud?” I didn't put anything, it was just ultrasonic humidifiers to create the cloud. I mean, the thing that really made me so well humbled by, by having been, in a way, the, the author, was that people felt some kind of lightness of being as a result of, in a way, dispensing with their appearance.

Question 2: Hi. I really admire your appreciation for materiality and listening to you talk about iron and how it's the common denominator between, you know, ourselves really and the earth. It got me thinking about the intersection of spirituality and science and how they're often seen as so disparate. Now, my question to you is about, the elemental, where we come from. We are all stardust. We all return to stardust. Oxygen, Nitrogen, Carbon are the building blocks of who we are and where we go.

Thinking about our bodies as subatomic particles. Is it possible that you know the body as is more an illusion than you're perhaps giving that credence and that yes, the body is the most important vehicle, but theoretically the body doesn't even exist as more than just accumulation of molecules. So I'm curious about, you know, the questions and answers that you are both seeking to ask and give and you know where you think it's headed in the future.

Antony Gormley: There are no answers in my work. There are only questions and they are pretty much your questions. In other words, if the only permanent condition that we are certain about is change itself, and if the bodies that we inhabit are simply elements that are in total kind of circulation, always in transformation, that is I think the truth that I'm hoping that the work helps us helps us recognise.

Arturo Galansino: I feel a little bit lost in my bodies and, uh, I dunno how do you feel? But I think it's a great thought to close this talk and to end here the Frieze Masters talk 2025. Thank you very much. Thank you.

ET: Thank you for listening to series four of the Frieze Masters podcast. Keen to hear more episodes like this one? Explore series one, two, and three of the podcast for more centuries spanning conversations. The Frieze Masters talks programme and podcast are brought to you by Frieze in collaboration with Dunhill. The Frieze Masters podcast is a Reduced Listening production.

Further Information

To keep up to date on all the latest news from Frieze, sign up to our newsletter at frieze.com, and follow @friezeofficial on Instagram, Twitter and Frieze Official on Facebook.

Main image: Antony Gormley, Land, Sea and Air II (1982). © The artist.