Ideal Syllabus: Tom McCarthy

Shortlisted for this year's Man Booker Prize, author and artist Tom McCarthy list the books that have influenced him

Shortlisted for this year's Man Booker Prize, author and artist Tom McCarthy list the books that have influenced him

William Shakespeare

Macbeth (The Arden Shakespeare, London, 2003; first published in 1623)

When my mother told me the story of Macbeth, she made it clear that it was written by Shakespeare. So he became a character as well, over and above Macbeth. And I thought: ‘That’s who I want to be – Shakespeare.’ So I borrowed a neighbour’s typewriter and started writing Macbeth, by Tom McCarthy.’ Unfortunately the manuscript hasn’t survived.

Thomas Mann

Tonio Kröger (Published in one volume with Tristan and Death in Venice, Penguin Books, London, 1955; first published 1903)

Mann’s novella made me understand the Macbeth-era fissure between character and writer all over again as a teenager. You’ve got Tonio’s contemporaries, traversing the surface of events unplagued by self-awareness; then Tonio, who longs for that naivety denied him by his writerly Erkenntnis, his consciousness of the symbolic structures that frame everything.

Joseph Conrad

Heart of Darkness (Penguin Books, London, 1995; first published 1902)

I must have known a third of this book by heart at one point. Nothing was ever the same again after it.

Maurice Sendak

Where the Wild Things Are (Harper & Row, New York, 1963)

Essentially Heart of Darkness done as a children’s book. It’s got near-identical sequences: Max becoming King of the Wild Things/Kurtz, ‘taking a high seat among the devils of the land’; the Wild Rumpus/‘unspeakable rites’; the anguished cry of the dark mistress as Max/Kurtz leaves to return to European ‘civilization’.

James Joyce

Finnegans Wake (Faber and Faber, London, 1939)

The source-code of the novel, of all novels – the matrix of their possibility laid bare. Presents the same challenge to any serious writer as Kazimir Malevich’s White on White from 1918 does to painters.

Hergé

The Castafiore Emerald (Methuen, London, 1963)

I probably learnt more about narrative structure from Hergé than from any other writer – and he’s not even a ‘proper’ writer! This book performs every narrative manoeuvre, every trick of misdirection, jamming, splitting, doubling, skidding and so on, to perfection, and does this at a Wake-like degree-zero of writing: nothing happens in it.

Thomas Pynchon

Gravity’s Rainbow (Vintage, London, 2000; first published 1973)

I read this at 19 or so and just thought, like, fuck, wow: this is the marker, the pace-setter for the contemporary novel.

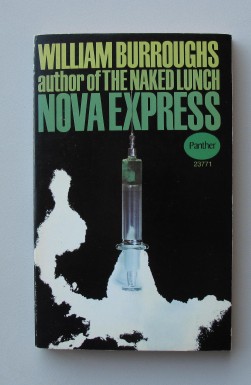

William Burroughs

Nova Express (Panther Books, London, 1964)

Burroughs is like a long-form poet: he makes prose do what usually only verse can. Cut language up and the world leaps out, in the words of Gerard Manley Hopkins, ‘like shining from shook foil’.

Jacques Derrida

The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1987)

Philosophy as a long open (if encrypted) letter sent from Socrates to Freud and back again; writing as technology, as transmission; and transmission as love.

William Faulkner

The Sound and the Fury (Penguin Modern Classics, London, 1976; first published 1931)

The single best novel ever written.

Alain Robbe-Grillet

The Voyeur (One World Classics, Richmond, 2009: first published 1958)

Structure, geometry, repetition – and at the heart of all of these, psychosis. Genius.

Herman Melville

Moby-Dick (Vintage, London, 2007; first published 1851)

I could say the same thing about this as about The Voyeur – the difference being that Moby-Dick occupies the opposite end of the spectrum, as the ultimate maximalist novel. I love the way lots of the chapters start out explaining some boring technical point about maritime law and work themselves up into wild, lyrical visions about history, desire and human frailty.

Maurice Blanchot

The Gaze of Orpheus (Station Hill Press, Barrytown, 1981)

To say what literature essentially is or isn’t is a doomed undertaking. But Blanchot feels his way better than anyone else around the outlines of what it might be: a space (of disappearance), a mode (of being-towards-death), a demand (impossible to satisfy) and a seduction.

Tom McCarthy is a writer and artist who lives in London, UK. His novel Remainder (first published by Metronome Press in 2005 and by Alma Books in 2006) won the 2007 Believer Book Award and is currently being adapted for cinema by Film4. The activities of his (perhaps fictitious, perhaps not) avant-garde art ‘organization’ the International Necronautical Society take the form of publications, declarations, exhibitions and events. His new novel, C, which he describes as ‘being about technology and mourning’, will be published by Jonathan Cape in 2010.