Life Stories

Why are there so few biographies of African artists?

Why are there so few biographies of African artists?

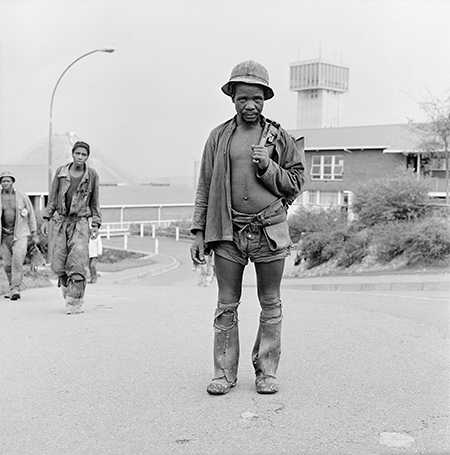

David Goldblatt, the octogenarian Johannesburg-born photographer, known for his unhurried images of South Africa and its many complications, drives a white diesel four-wheel drive. He bought the demonstration-model Isuzu pick-up in Cape Town just over ten years ago, and had a Pretoria engineer fit a custom-designed ‘caboose’ (as he refers to the campervan lodgings bolted onto the rear) for exploratory trips into the wilderness. Two years ago, I watched as the novelist Nadine Gordimer – whose prose Goldblatt admired as a young man and with whom he later collaborated on his debut book, On The Mines (1973) – awkwardly trying to climb into his terrestrial galleon after a public interview. ‘You should exhibit that car,’ I remarked, only half joking. Goldblatt frowned. Months later, I questioned him about his choice of wheels.

Goldblatt has owned all sorts of vehicles since declaring himself a professional photographer on 15 September 1963. They include a bicycle, a Peugeot 403 and a bmw 600 motorcycle; the latter was used during the making of In Boksburg (1982), an essay on a whites-only mining town east of Johannesburg. Does it matter that this book-length essay – which tanked on its commercial release but is due to be republished by Steidl later this year – was produced by an easy rider on a motorcycle? Probably not. But at what point does anecdotal chat about an artist’s means of transport shift in register and become biographically and/or critically significant? Francis Picabia, for instance, owned 127 cars during his lifetime – at least one of which is pictured in Calvin Tomkins’s 1997 biography of Marcel Duchamp.

Cars, certainly for Goldblatt, are mere tools of the trade. ‘The logistics of the photographer in the field are interesting to me, and they are a vital clue, often, to the way the photographs were conceived and made,’ he said. ‘To me, the means of getting to a place are absolutely primary; they are as primary as the camera itself.’ I had never thought to question Goldblatt about his problems with dodgy electrics and ropey bodywork. Afterwards, I wished I had done it sooner. While oblique, his response offered an unpretentious insight into a free-spirited man who, in 2004, told me, by way of a confession about his ‘moments of extreme unhappiness and doubt’, that he sometimes felt his work ‘doesn’t seem to get enriched by new seeing: I keep seeing the same bloody things and treating them in the same bloody way.’

Greg Marinovich, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer, filmed our conversation and included part of it in his 2005 television documentary Conversations with Goldblatt. Goldblatt’s white Isuzu features prominently. A tv documentary is, however, not a biography. There is no standalone biography on Goldblatt, just an uneven paper trail of critical writing and an opaque novel by Ivan Vladislavić, Double Negative (2010), in which Goldblatt is recast as the fictional photographer Saul Auerbach. A while ago, I asked a Johannesburg publisher why there are so few artist biographies published locally – a situation that is even more dire elsewhere across the African continent. Not sure, they replied. The ascendency of critical theory and artist monographs featuring multiple essays only partly accounts for a shift in publishing tack.

Biography, as John Berger reminds us in The Success and Failure of Picasso (1965), tends to perpetuate personality cults. In South Africa, though, biography is a resourceful tool for digging through the muck of the past: in short, for recovery. Angela Read Lloyd’s The Artist in the Garden (2009), recounts the life of forgotten landscape painter Moses Tladi, the first black artist to exhibit at the National Gallery in Cape Town, in 1931, while N. Chabani Manganyi’s I Am an African: The Life and Times of Gerard Sekoto (2004), tells the story of this piano-playing figurative painter who, in 1947, moved to Paris, nearly a decade after his pal, the abstractionist Ernest Mancoba. ‘I do not consider biography primarily as a narrative preoccupation with individuals as individuals,’ Manganyi, a clinical psychologist, told me in 2008. ‘A delicate and very important balance needs to be arrived at.’

Which is why Goldblatt, whose life straddles a tumultuous period in South Africa’s political and cultural life, is perfect for a biography. ‘Nooit,’ responded Goldblatt, using the Afrikaans word for ‘never’, when I put it to him. He then shyly smiled. ‘My life is just not that interesting.’