The Liverpool Biennial’s Blinkered Approach to Feminist Art

The exhibition at Tate Liverpool takes women’s liberation as its basis, leaning on frustratingly narrow definitions to justify connections between Linder and Martine Syms

The exhibition at Tate Liverpool takes women’s liberation as its basis, leaning on frustratingly narrow definitions to justify connections between Linder and Martine Syms

The title of this year’s Liverpool Biennial, ‘The Stomach and the Port’, postponed from 2020, refers to the central role the city played in the Atlantic slave trade. Almost half of Liverpool’s trade was with Africa and the Caribbean in the second half of the 18th century, with one in five enslaved people brought through its port, which was also used for importing goods like tobacco, coffee and sugar from the New World. You know the Beatles song ‘Penny Lane’ (1967)? James Penny was a slave trader.

The exhibition at Tate Liverpool (which has its own, less direct relationship to slavery) is curated by the Biennial’s curator, Manuela Moscoso. The press release states that the works are ‘interlinked through […] feminism as a form of rebellion against the dominant narratives of white, heterosexual, male power’ and a political orientation that takes as its aim the liberation of the many over the few, regardless of gender. This is a laudable and urgent aim, but the show has a rather dated perspective on feminist art, as well as a somewhat blinkered approach to the aims of the biennial itself.

Global strategies of revolt drive Ines Doujak and John Barker’s Masterless Voices (2014), a carnivalesque musical by the Austrian artist and British writer, exploring themes of rebellion and utopia through a series of surrealist video vignettes. The work begins with a prologue featuring stomach microbes dressed as harlequins with overlarge heads and exaggerated curls that look – in a moment of eerie prescience – like COVID-19 spikes. One of the gut flora stands at a DJ’s mixing table, which looks like it’s being used to build a bomb, singing about drums, personal trainers, love and rage; of ‘masterless voices/singing songs in the dark’. The rest is surreal, sparkly and kinetic: a mountain dances by itself, voiced by a throat singer describing how men sought glory climbing his skin, then plumbed his insides to see what he was worth. Cut to a carnival in Bolivia; brass players, drumming, dancing; all the festivities of the gut now out in the air. Cut to a group of Black men dancing in a small courtyard, joined by a younger boy who looks overjoyed to be there.

As joyful and beautiful as these dancers are, there is something off in the way they perform for a film directed by two white artists. The men make a strange and troubling parallel to the harlequin stomach dancers. If the biennial is meant to call attention to economic systems whereby white people get rich off the labour of Black people, Masterless Voices feels suspiciously like more of the same. Whatever these men were paid for their dancing, it’s hard to imagine it equating to the commission the artists are likely to have received for their work, and the cultural capital they accrue by means of it.

American artist Martine Syms’s Borrowed Lady (2016) stages a smarter challenge to the circulation of Black bodies through a process of mimicry: on four screens, artist and poet Diamond Stingily mimes gestures and facial expressions typically used by white people in reaction gifs on social media. Images and text jump from one screen to the next against a purple backdrop. Building on Syms’s ongoing investigation into the social history and dissemination of emotive movements, particularly in relation to Black femininity, Borrowed Lady captures not only the racial politics of social media but also its hyperactive state of distraction.

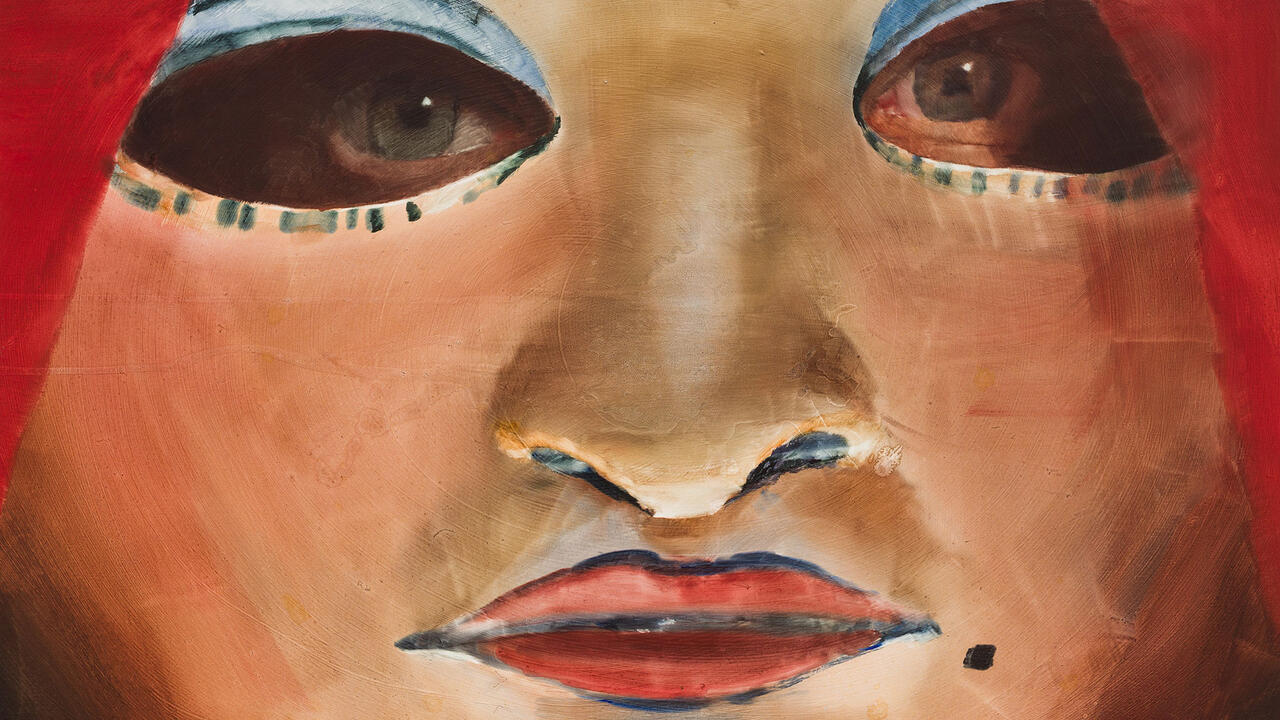

The undoubted star of the show, however, is Jamaican artist Ebony G. Patterson, with her dazzling and difficult contributions …fraught…for those who bear/bare witness (2018) and …when the cry takes root… (2021). These two, enormous, multi-layered tapestries drip with decorations: fake butterflies; dusty, wilting flowers; photographs; a sequin hummingbird; a big, jewelled spider; a diamanté lizard. Everything natural made artificial, like Jean des Esseintes’s jewelled tortoise, which collapses under the weight of its own embellished shell in Joris-Karl Huysmans’s novel Against Nature (1884). The effect is an explosion of texture, a riot; there is violence here. The outlines looks like continents – Europe, Asia – where there are no borders, just tears in fabric and needlepoint; the sense that the work is not just built up, but that it might actually be in a state of entropy.

Specially commissioned for this show, …when the cry takes root… is essentially a giant tapestry ship, partly suspended from the ceiling by fishing line, as if caught while drifting along the gallery floor. At its prow, a peacock perches on gold conch shells like Venus rising from the waves, its feathers made of black Mardi Gras beads (complementing the carnival theme in Masterless Voices); beads spill off the vessel on both sides, which is bordered by racy kitchen gloves trimmed in red lace. Brown hands stick out here and there, one palm up in a wave or to beseech or just to stretch in this long journey across the Atlantic. Beneath all the glove ruffles is a dead body made of glass. These seemingly infinite details are part of the point; the work of art is inescapably kitsch in the face of slavery and colonialist exploitation, but we piece it together anyway, because that’s all we can do: keep endlessly gluing sequins to our tapestries.

While the intersectional approaches of these video works overlap with histories of women’s liberation, they differ from other more self-consciously feminist pieces on show, like Judy Chicago’s ‘Through the Flower No. 2–4’ (1972), which – despite being seen as a foundational series in the field of feminist art – seems to suggest, reductively, that the female body is organized around a central absence. The punk photomontages on display by Linder are not her best or wittiest, in my view, although the crowded layering of nude men, women, flowers and bugs (one model’s stockings cunningly echoing a bright yellow caterpillar) frolicking in some Edenic space in Daughter of the Waters (2017) nicely echoes Patterson’s work. Still, for Chicago’s central-core imagery and Linder’s pin-up girls, however subversive, to be the show’s most explicitly feminist artworks felt narrow and frustrating. Hanging nearby, the swoopy genital shapes in British surrealist Ithell Colquhoun’s paintings, such as Earth Process (1940) – which are much weirder and more explicit in their global, earthy message of seasonal cycles and energy taken from and given back to the earth – looked essentialist in their company.

The final room speaks back to Chicago’s images with ironic, knowing intent. The German artist Jutta Koether’s A380 naked (2020) shows us an airplane with boobs against a sky of boobs, with a border made of boobs and beautiful, amorphous markings on the bottom, like scarves being waved in semaphore – all of it in the brightest shades of pink and orange. Building on the artist’s ongoing inquiry into the ‘creaturely’ aspect of inanimate objects, this feminization of a technology not widely associated with women is a defiant statement in favour of prettiness in art, and a redemption of colours and images associated with ‘femininity’. As the trans writer Andrea Long Chu writes in her 2019 book Females: ‘Everyone is female, and everyone hates it.’

Main image: Ebony G. Patterson, …when the cry takes root…, 2021, installation view at Tate Liverpool, Liverpool Biennial. Courtesy: the artist and Liverpool Biennial; photograph: Rob Battersby