New Sweden

Re-evaluating modernist housing at Tensta Konsthall

Re-evaluating modernist housing at Tensta Konsthall

On 28 February 1986, Olof Palme, the Swedish Prime Minister, was assassinated in a Stockholm street. A newspaper report, published in Dagens Nyheter the following day, claimed that a ‘suspected perpetrator’ jumped into a Volkswagen Passat and turned left ‘in the direction of Tensta’.

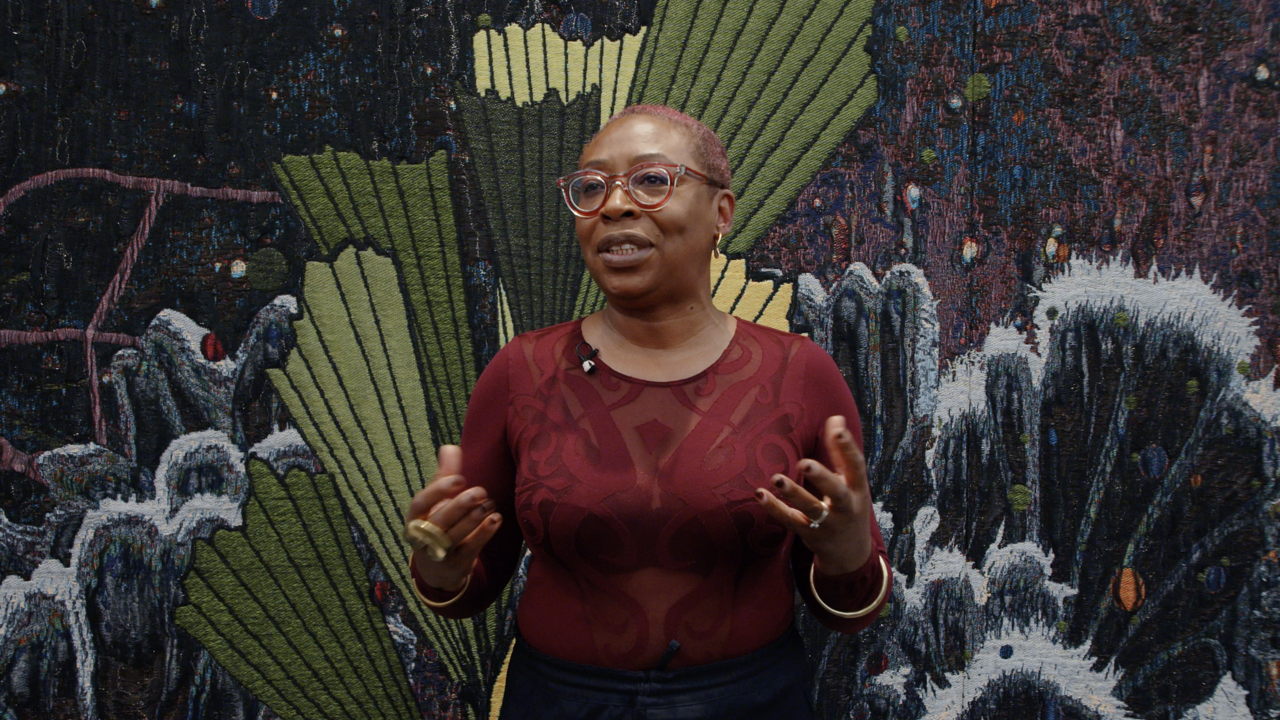

The Stockholm suburb of Tensta may not have been on world news front pages since, but it offers a striking cross-section of Swedish history. At its epicentre stands an early-1970s modernist housing project, but the area is also host to iron age graves, a 12th-century church and a former military training ground that has since been repurposed as a nature reserve. ‘When I started working here three years ago,’ says Maria Lind, director of Tensta Konsthall, ‘it was immediately clear to me that the area is unusually rich in terms of both historical and contemporary cultural references. Since my great-grandmother lived here when I was a child, I knew that there were numerous archaeological artefacts from the bronze and iron ages, yet the area is probably best-known today for its modernist housing estate, which operates as a sort of migrant ghetto.’ The suburb’s 19,000 inhabitants, Lind maintains, are still not really included as part of the country’s image of itself.

Sweden continues to be perceived by many as a paradigmatic, well-functioning social democracy. Yet, given the significant neoliberalization the country has undergone since the 1980s, such a view is outmoded, and the Konsthall’s current exhibition, ‘Tensta Museum: Reports from New Sweden’, addresses precisely this misapprehension. ‘New Sweden’, explains Lind, ‘is a country in which the divide between the rich and the poor is increasing at a faster rate than in any of the other 34 countries of the oecd [Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development]. The welfare state is far from what it used to be, with the deregulations of the 1990s having continued apace, regardless of each successive government’s political leanings. It is not widely known that Sweden – and Tensta in particular – has been used as a testing-ground for numerous neoliberal policies and tactics. Public housing in Stockholm, for example, has been privatized at an unprecedented scale and pace.’

The Marxist theorist David Harvey has argued that Sweden’s neoliberal turn was prompted by the panicked reaction of political elites in the 1970s to the very real prospect that the country would be transformed into a worker-owned democracy. The shift to neoliberalism in Sweden has been less obvious to non-nationals, because it has happened in a much stealthier fashion than in places such as the UK and Italy, where the vehement reaction to 1970s left-wing militancy was accompanied by a heavily trumpeted repudiation of any hint of socialism.

The exhibition at Tensta Konsthall consolidates the growing notion that the revulsion against vernacular modernist aesthetics – the modernism in which people lived – was simultaneously a rejection of a better organized and more democratic society. Tensta’s modernist housing development was built on the back of an international movement committed to relocating the poor from squalid slums to well-equipped modern dwellings, and a number of works in the show attempt to recover the reputation of this much-maligned architectural style. Sabine Bitter and Helmut Weber’s From Our House to Bauhaus – Occupy Modernity (2012), for instance, is an image-essay wallpaper installation that challenges the reductive account of modernist housing given by Tom Wolfe in his 1981 book From Bauhaus to Our House. Thomas Elovsson and Peter Geschwind’s installation, Apollo Pavilion – Re-worked, rethought, remixed, retold (2013), reconstructs the Apollo Pavilion, built in 1969 in Peterlee, near Newcastle, as part of Britain’s new town project; while Terence Gower’s Tlatelolcona (2008) is a cardboard model of architect Mario Pani’s original plan for a housing development in Mexico City, which later became infamous as the site of a massacre of student protesters by the Mexican army. The comparative autonomy and stability that the democratization of housing gave to previously marginalized groups is thrown into sharp relief by a series of watercolours by Josabeth Sjöberg, which depict in remarkable detail the modest rented rooms that were all the artist could afford as a single, working woman in Stockholm in the 1800s.

However, rather than reifying social democracy as the best solution politics can ever hope to deliver – which, given our current state of post-crash ‘austerity’, would not have been unreasonable – ‘Tensta Museum’ provided visitors with the opportunity to consider the present day from the perspective of lost futures that could still be recovered. The very title of the show, temporarily re-labelling the Konsthall a ‘museum’, offers a hint: in common with many such cultural institutions, the Konsthall receives only half of its funding from public bodies, and it has to re-apply for this support every year – an anxiety-inducing neoliberal practice that Lind attempts to counter, noting that a museum typically has the ‘stability and continuity’ that a precarious ‘project’ such as Tensta Konsthall lacks.

The exhibition includes a cartoon by the satirist Markku Huovila, made in 1995, and inspired by the newspaper report from 29 February 1986. Looking at the image, I find myself wondering whether ‘New Sweden’ was, in fact, born the day Palme, a critic of both western capitalism and Soviet aggression, died. In both Sweden and the UK, it was during the 1980s that the hopes for a new leftism, a leftism that would have exceeded social democracy, were killed. From then on, ‘new’ would only mean ‘neoliberal’.