Possibilities of Creation

Daniel Birnbaum, curator of the first Frieze VR exhibition, Electric, speaks to artist Rachel Rossin about VR's past, present and future

Daniel Birnbaum, curator of the first Frieze VR exhibition, Electric, speaks to artist Rachel Rossin about VR's past, present and future

Daniel Birnbaum You work in installation, painting and virtual reality. Do your physical works anticipate what you realize in VR?

Rachel Rossin Sometimes a discovery in painting ends up being something that can lead into a virtual reality piece. My understanding of spaces completely changed once I started making paintings from virtual reality. I look now at the Hudson River Valley painters and there’s almost this… it’s not a smell, but you know that quality in those paintings? An openness, an uncanniness, a sense of the screen...

DB I believe certain artists have anticipated the capacity of VR before it was even a concept. Marcel Duchamp included mathematical dimensions in his work, invisibly. We’ve spoken about Hilma af Klint, who thought she was painting things that cannot be seen, and translating her works in VR. Is that something you would actually want to do?

RR Because I love and appreciate her work so much, it’s very easy to want to do that. I’ve been talking about how painters capture space. Af Klint is thinking about this too. The shallowness of those paintings. There’s something that feels like it’s working from the wake of a movement through space or something: a sort of recursiveness.

DB She had this utopian idea of building a spiral structure for displaying her work, that she refers to as a temple. With VR, one could actually help her finally realize it.

RR It’s very straightforward. She already left us directions: it’s just executing something in technology that she didn’t have access to.

DB I think once or twice in every century there’s an innovation that changes the possibilities of creation, and there’s a little window of opportunity before we define how it’s used or not used. Do you think we’re at the beginning or the end of that window for VR?

RR Very much at the beginning. There’s still so much more ground to explore. Right now we’re dependent on rendering. On the technical side, things are moving very fast. Our methods are all going to shift very quickly, and the electronics themselves too.

DB You are perhaps unusual because you’re an artist but also a programmer and coder. You have basically created these works in this high-tech medium yourself. Are you self-taught?

RR Yes. But I think all programmers are self-taught. And you continue to be self-taught because it’s always changing. The first things that I was making were really small applications: video games, but also non-games, like a sandbox or some sort of experimental world. Virtual reality for me is the intersection of programming games and installation art.

DB There’s a tradition in contemporary art of creating immersive environments in vast spaces like Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London. Do you think the spread of VR will make achieving this kind of effect too easy?

RR I don’t know if there’s such a thing as ‘too easy’, because then that just starts to move what the threshold is. It is becoming very easy to make things look really lovely in VR. The harder things are the ideas, of course.

DB What can you say about the piece you’ll show in ‘Electric’?

RR In Man Mask (2016), I’m performing a body-awareness meditation from inside of a Call of Duty character. It’s my voice speaking, but you’re inside this exploded video game world, where I’ve hacked all of the assets. It’s actually the only passive 360 piece I’ve made.

DB On one level, one could say the medium is only fully explored when it involves all kinds of interactivity. But then, we couldn’t show it to thousands of people, which is the plan here.

RR I think this is a good plan.

DB I’ve often seen VR being presented in art contexts in a marginal slightly sad way. Do you think VR will disrupt traditional ideas on where art is shown, and how it can reach audiences?

RR In Paul Valéry’s ‘The Conquest of Ubiquity’ (1928), he talks about being able to recreate an orchestra as if you’re sitting in front of it. That is a very large appeal for live virtual reality as a medium for experiential art. But there are more radical possibilities. I’ve been doing a lot of experiments with VR chat, and there’s so much empathy in the way people are communicating with each other. Those types of interactions will change access to art, yes.

DB There is sometimes a critical impulse attached to VR, that it’s somehow solipsistic; I always say that reading a novel is also something you do alone. Do you think it’s just a misunderstanding that VR is somehow a lonesome medium?

RR I think right now it can be. In VR chat, you can tell the people who are just looking at it and aren’t very engaged, and those people are not just engaged, but even take on added qualities: someone who’s appearing as Kermit starts to act like Kermit. So it is social. Also, and maybe this is a little too grandiose, but I know that there are major companies having VR conferences so that people don’t have to fly across the world. Think about the environmental impact of that...

DB I’ve been thinking about that too, being one of the worst when it comes to going everywhere for biennials etc. In the future, maybe there can be another kind of international dialogue through this omnipresent medium. The art world as I know it will always want moments of commonality where we meet and gather and have real exchanges. Speaking of exchanges, who are the people in this field who push you in some direction or inspire you?

RR Gretchen Bender is amazing. The amount of presence she brings to her work. She has an awareness of this terrain’s potential for ‘evil’, and puts that into a place that is hopeful and not didactic. You were talking, earlier, about the Duchamp… what piece specifically?

DB It’s to do with the Large Glass (1915–23). Actually, there’s a group in Frankfurt who’ve turned the work into machinery, so it comes alive. Even people who spent decades thinking about the Large Glass understood it anew when they saw this version.

So if artists anticipate the possibilities of technology, technological developments also sometimes show us new sides of art we think we already know.

Electric, a VR exhibition curated by Daniel Birnbaum, is on view at Frieze New York throughout the week. ‘Electric’ is realized in partnership with LIFEWTR, a premium water brand committed to advancing emerging artists on a global stage. By providing headsets, which pair with phones allowing users to view the exhibited VR works through the Acute Art app, ‘Electric’ can be enjoyed by audiences beyond the fair.

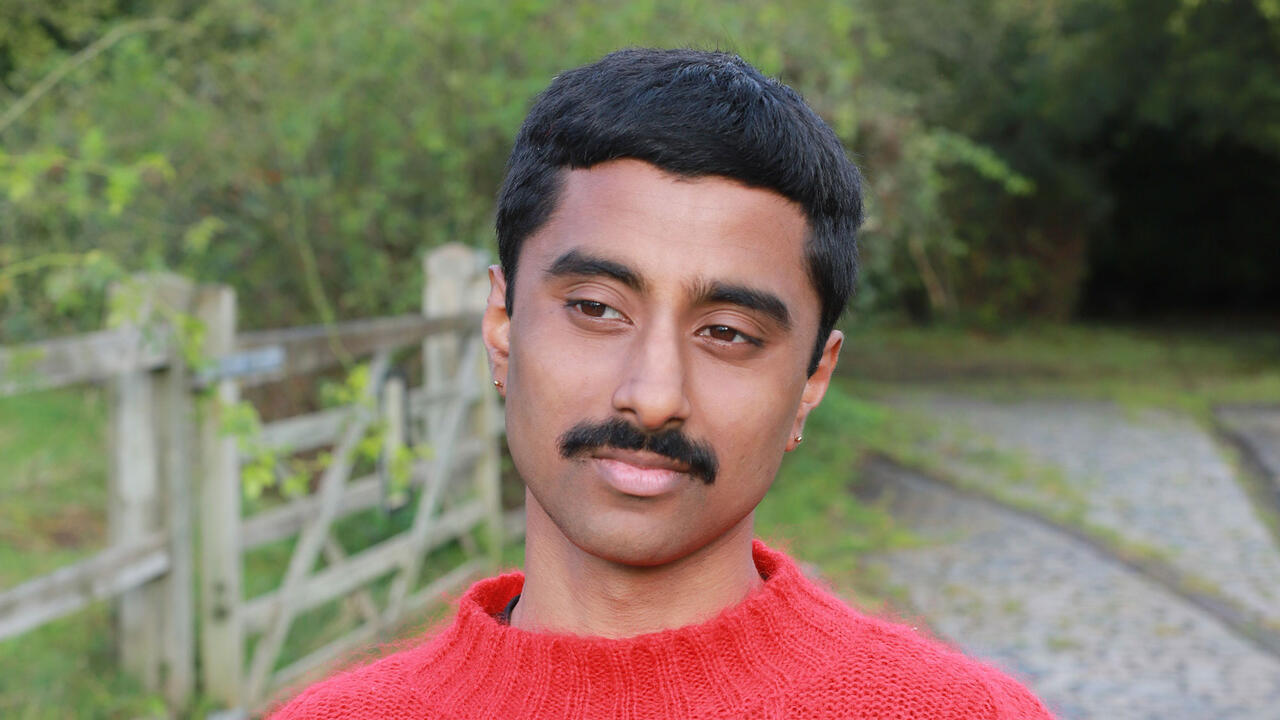

Rachel Rossin is an artist, based in New York City, USA. Recent and forthcoming exhibitions include Zabludowicz Collection, London; 4a, Hamburg, Germany, and Akron Art Museum, Akron, Ohio, USA.

Main image: Rachel Rossin, The Sky is a Gap, 2017-19. Courtesy: the artist and Zabludowicz Collection, London