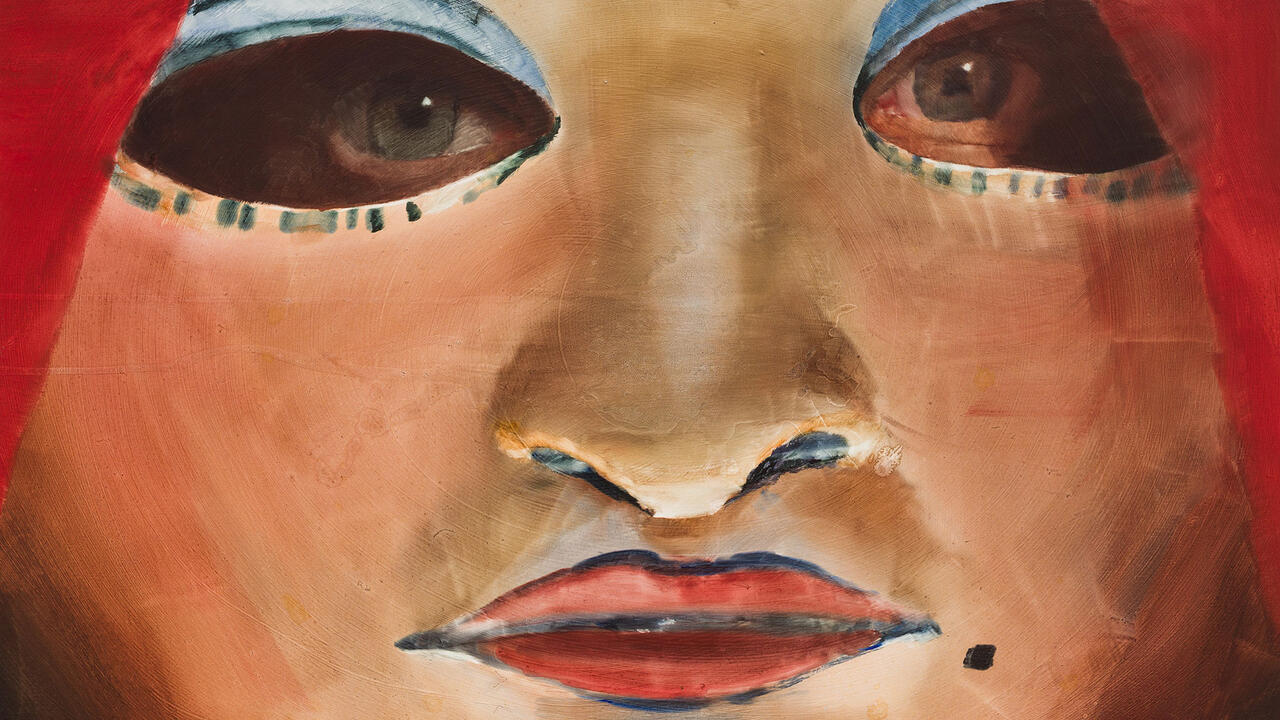

Un oscuro día de justicia (A Dark Day of Justice)

Rodolfo Walsh was a translator, proofreader and writer of detective fiction, short stories and autobiography, although he is best known for his pioneering books of investigative journalism, or testimonios, which preceded the later wave of New Journalism in the USA by several years. An Argentine of Irish descent born in 1927, Walsh is less cited outside Latin America than his literary compatriots Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares or Julio Cortázar, but he was a writer of comparable talent to his more famous peers, and perhaps of greater courage. He repeatedly risked his life attempting to uncover the brutalities of military regimes in Argentina from the 1950s to the ’70s, until he was eventually murdered by government forces in 1977.

As published in this edition by Amsterdam’s Missingbooks series, Un oscuro día de justicia (A Dark Day of Justice) comes as a small pair of books in Spanish and English: one a facsimile of the original 1973 edition, the other a fluent translation. In the colophon the publishers highlight the exiled, displaced status of the book and its circuitous path across the globe – it was smuggled out of Argentina to Paris before eventually finding a place in Amsterdam University Library. Represented in this way, it appears as a tiny fragment of a vanished, though still sorely remembered, reality: bearing the imprint of the circumstances of its making as much as some lost and refound coin.

The central text itself is not reportage but a fictional short story of brilliant compression, set in the world-within-a-world of an Irish boarding-school in Argentina. It is accompanied by an interview from 1970, in which Walsh emerges as an impassioned thinker about genre, defending his vision of the forms of ‘testimony and reporting’ against the dominance of the novel, and objecting to the taming of facts and realities by their transformation into fiction: ‘the attempt to take all danger out of art’. In the appendix the Dutch journalist Jan van der Putten contributes an essay, revealing just how much, and how dangerously, Walsh applied his theories.

This framing of Walsh as a stridently political writer of non-fictional testimonies pulls rather hard against the traditional form of this short story, which initially recalls nothing so much as early James Joyce. But it does bring its strong allegorical intent into clear focus. Perhaps too much so, since the ‘meaning’ of the allegory (about dictatorship) threatens to drain away the subtlety with which Walsh invests every curl of every sentence. His work often rejected the demands of fiction, tackling reality in a much tighter grasp. He never wrote any of the novels he planned: ‘Nobody demands a novel from Borges’, he said, protesting slightly, in an interview. Yet this short story is perfect in its way, carrying a very heavy load without seeming clumsy.