Why Covid-19 Might Be Our Chance to Reimagine the Arts

We should use this moment to propose new ways of making and showing

We should use this moment to propose new ways of making and showing

‘A wave of withdrawal is reshaping the political landscape … Tremors can be felt from the global Shy Underground… From the boardroom to the bedroom.’ As doors close during the lockdown, shuttered exhibitions, theatres, cinemas and clubs have left culture in a lurch. It’s time, then, to rethink the nature of that cultural experience itself.

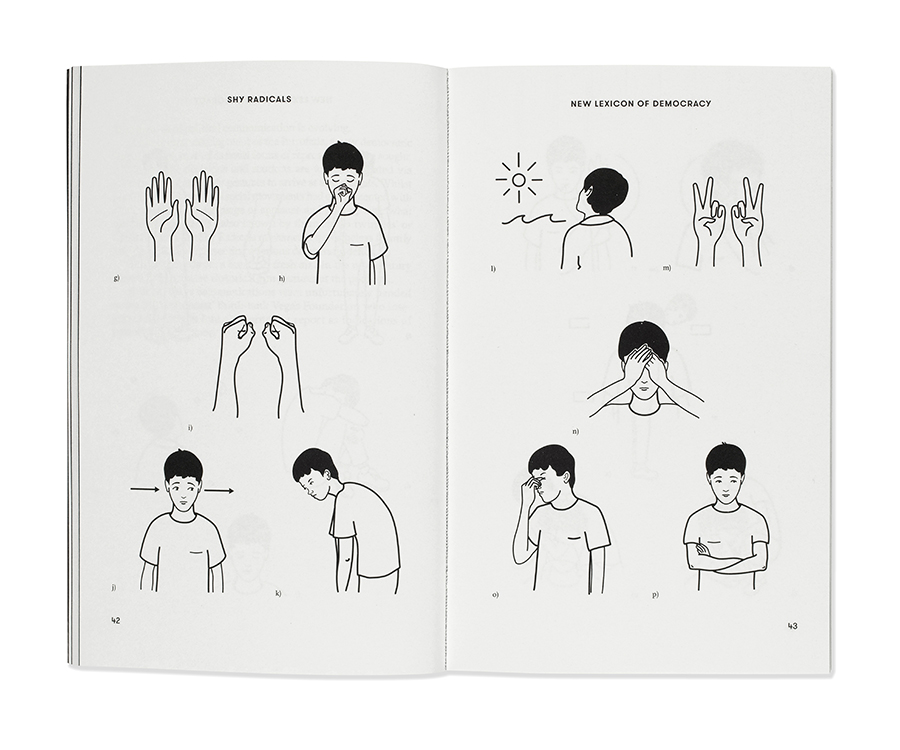

In a way, the world is catching up with the vision of artist Hamja Ahsan’s manifesto, Shy Radicals (2017). Ahsan’s book called for a ‘pan-Shyistic’ society of introverts, the asocial and the reclusive. Challenging what he calls ‘extrovert supremacy’, Ahsan proposes a speculative Walden pond for our moment of hyper-visibility, livestreams and influencers. This state would ensure its citizens ‘freedom from small talk; freedom from coercive visual distraction; freedom from enforced jollity’. Its constitution proclaims: ‘No one shall be required to attend or perform at social gatherings.’

When Ahsan published Shy Radicals, it was intended as serious satire. But, seen today, it gets at something larger: that this moment of ‘enforced extroversion’, which privileges those who speak loudly at meetings and those who beam themselves on screens, may only exacerbate existing disparities. And, as some galleries shut forever while others will reopen, we’re seeing how those same disparities have long marked cultural production, a realm in which visibility itself is monetized.

Let’s face it: even before Covid-19, the art world had become shot with hand-wringing and tepid apologies. Even among those professionals most beholden to it, the art business was becoming commonplace to poo-poo: environmentally-taxing plane rides, unethical museum boards, many-tentacled mega-galleries and cookie-cutter biennales in every corner. Don’t get me wrong, I love much about this system: but in its recent form, it was becoming impossible to justify. I’m probably not the only one to wince at profiles of social media managers in newspapers. Biennales as a gambit for city tourism (read: gentrification) make me uneasy. And: ‘Who cares about institutional politics when the world is on fire?’ as a writer friend wrote to me in January.

I welcome the moment where shows will open again. But how might we rethink the art world after Covid-19 to be more equitable, more varied, less winner-take-all? Just as arte povera – ‘poor art’ – took hold amid anti-capitalist unrest in post-war Italy, then we should look to the potential of simple means, now. Ahsan’s art imaginatively employs simple means – text on paper – not million-plus dollar programming tools. If, as William S. Burroughs wrote, ‘language is a virus’, then it follows that words, something we all have, can be a vaccine, too.

In frieze we recently ran a profile of the Nobel Prize-winning author Olga Tokarczuk, who lives in Wrocław, in western Poland, where she also runs a short-story festival. On 31 March, she published a nuanced essay in Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper tactfully posing a provocative question: are these coronavirus times not, perhaps, in part a return to normalcy?

Tokarczuk wasn’t being callous. She lamented the ‘dictates of hyperactive extroversion’, and articulated that – despite the very real health crises and global economic shutdown – we can finally attend to ourselves, to what’s in front of us and to the (fewer) people we do see. The author of Flights (2007) also decried the reality that borders in Europe are closing, recalling its pre-EU order. But I think we can attend to these facts – to our political realities – more clearly when our ears aren’t ringing with the foghorn of ‘content’, and when curators are not zipping around to the next ‘art summit’ in a Swiss chalet. This is a time for imaginative proposals, not prosecco at private views.

‘Isolation is a state of mind,’ I wrote in my recent profile of the artists Vivian Suter and Elisabeth Wild. I was lucky to visit them in Guatemala before this all started. They told me how, in a town with few shops and no mail, they struggled to get oil paint, canvas, paper. And Wild, who died soon after, took to collages after she couldn’t paint – the added restrictions of the body. I see them, now, as shy radicals: people who could make partly because of the difficulty they had to access, to see things, not in spite of it. Their remoteness was an eerie premonition of what was to come – the bad and the good of our new, very isolated age.

Elsewhere in Europe:

In Germany, last week brought good financial news for many artists, freelancers and small business owners. Germany gave out over 1 billion Euros in no-strings-attached relief funds – for many artists, that means that 5,000 Euros have already hit their bank accounts.

Hetty Berg started as new director of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, coming from Amsterdam’s Jewish Cultural Quarter.

frieze regular contributor Noemi Smolik won this year’s AKDV–Art Cologne Prize for Art Criticism. The award is usually given during Art Cologne, which has been postponed.

Claudia Perren, director of the Bauhaus Foundation in Dessau, is set to direct Basel’s HfGK, an art college.

Curator Stefanie Kreuzer is leaving Museum Morsbroich, in Leverkusen, for the Kunstmuseum in Bonn.

The Munich gallerist Barbara Gross is closing her space after 32 years. She was a longstanding champion of female artists, including VALIE EXPORT, Nancy Spero and Katharina Sieverding.

Asterix illustrator Albert Uderzo died, as did the composer Krzysztof Penderecki, best known for his ‘Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima’ (1960).

Galleries and institutions continue to explore new digital offerings. One highlight is the Basel gallery Weiss Falk, who have launched an online ‘cinema’ featuring the likes of Klara Lidén. Others, such as Berlin’s Barbara Thumm and Contemporary Fine Arts, are rolling out some of the more convincing virtual exhibition walkthroughs I’ve seen. Milan’s Massimo De Carlo opens its immersive ‘Vspace’ on 14 April.

For our ongoing series highlighting shows affected by the crisis, see here.